Asylum by Boat: Origins of Australia’s Refugee Policy

By Claire Higgins | UNSW Press | $29.99 | 256 pages

By global standards, Australia is at best a middle-level power, with a small population, a remote location and a limited capacity to project power beyond its own borders. And yet in the field of refugee policy the country has had a disproportionate worldwide influence. Relentlessly pursuing policies that undermine the legal and normative principles on which the institution of asylum is based, Australia is now the envy of the many other states, particularly but not exclusively in Europe, that wish to halt the spontaneous arrival of refugees.

A central component of Australia’s asylum policy has been Operation Sovereign Borders, a naval operation intended to identify, intercept and turn back refugee boats before they reach the country’s shores. Taking its cue from Canberra, the European Union has adopted a more extreme approach, subcontracting the task of interception and return to the Libyan Coastguard and militia groups that detain, abuse, exploit and enslave people seeking to cross the Mediterranean.

Most of the literature on Australia’s approach to the refugee issue covers the period since 2001, when John Howard’s government refused to allow a Norwegian freighter, the MV Tampa, to enter Australian waters because it was carrying more than 400 asylum seekers, most of them from Afghanistan. Shortly afterwards, Canberra introduced the Border Protection Act, confirming Australia’s sovereign right to determine “who will enter and reside in” the country, and the Pacific Solution, whereby asylum seekers were incarcerated on the small island state of Nauru, where their claim to refugee status was considered.

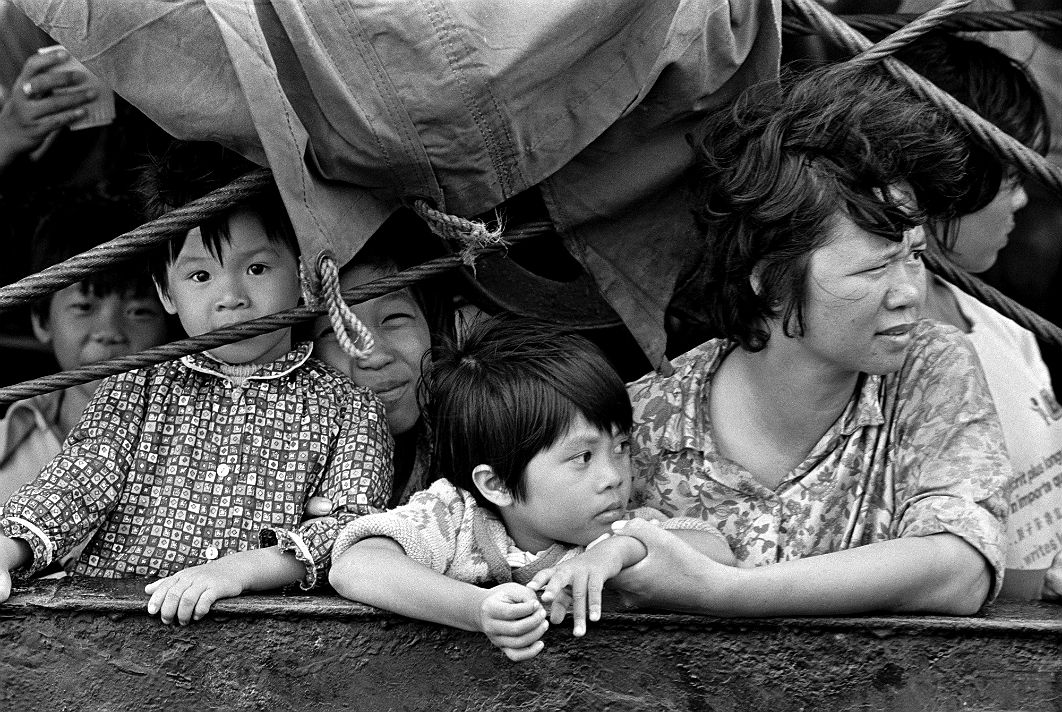

Claire Higgins’s new book breaks a considerable amount of new ground by providing a detailed account of Australian refugee policy-making between the mid 1970s and early 1990s, a period when a relatively small number of asylum seekers — around 3000 — arrived by boat from Vietnam, Cambodia and China. The figure was to grow substantially in later years, reaching a peak of around 17,000 in 2012.

Some commentators (including Malcolm Fraser, who served as prime minister between 1975 and 1983) have argued that this was an era of exemplary generosity. Draconian responses such as pushbacks and detention were considered but rejected. The resettlement of refugees from Southeast Asia was initiated and subsequently expanded. And, as Higgins explains, while successive governments were eager to control the arrival of “boat people,” they also felt that it would be advantageous for the country to honour its responsibilities and uphold the international rule of law.

Higgins’s account of refugee policy-making during this period neatly combines a chronological narrative with thematic analysis. A brief introduction outlines the methodology employed by the study, reviews the existing literature on the events that it covers, and presents the facts and figures relating to boat arrivals. Subsequent chapters focus on the government’s efforts to control the refugee story presented to the Australian electorate, the methods employed to ascertain whether the asylum seekers had a valid claim to refugee status (almost all were allowed to remain) and how resettlement was used as a means of limiting spontaneous arrivals.

The book concludes with an analysis of Australia’s relations with countries of first asylum in the region, an account of the country’s engagement with the international community on refugee issues, and an examination of the debate that took place within government and parliament on the fraught issue of detention. As chronicled by Higgins, a decisive point was reached in 1989, when an impending influx of Cambodian people prompted the authorities to place two newly arrived families from that country under house arrest. It was a first step towards what was to become Australia’s most infamous refugee policy: mandatory and indefinite incarceration.

There is a great deal to admire about this book. It is engagingly written, carefully avoiding academic or bureaucratic jargon. It tells a gripping story while providing key insights into the many variables and different stakeholders that played a role in determining Australian refugee policy during the period under review. It makes excellent use of archival sources, some of them previously unexplored.

Asylum by Boat also raises a series of questions that remain highly relevant today, not only in Australia but also in many other parts of the world. Do states have an obligation to admit refugees, or can they legitimately be intercepted and turned back? Should countries of origin and transit be persuaded (or bribed) to prevent the departure and onward movement of asylum seekers? And to what extent can creating safe and legal routes avert the need for people to embark on difficult and dangerous journeys from one country and continent to another? ●