No recession since 1974–75 has done less damage to the Australian economy in the short term. Yet, amazingly, the recession of 2008–09 has knocked the economy off its long-term track more damagingly than any other downturn for more than half a century.

And now Reserve Bank governor Glenn Stevens is pondering aloud whether this marks a permanent downward step in Australia’s potential growth rate. His thoughts are more than a little confusing, though, as the variety of media interpretations attests.

It might be best if we start by looking at what has actually happened.

First, the recession. You didn’t know that Australia, too, went into recession in 2008–09? No problem: “recession” doesn’t have a precise definition. The theory that two quarters of negative growth make a recession is a newspaper invention. In the United States, a committee of wise economists issues authoritative but inevitably subjective rulings on when the American economy enters and exits a recession. We have nothing comparable here.

But the noun “recession” comes from the verb “recede.” It means “going backwards,” which, to my mind, is exactly what happened to Australia in the wake of the global financial crisis. In just over a year, a net 200,000 people became unemployed. A net 240,000 others became underemployed: mostly because their full-time jobs suddenly became part-time.

The unemployment rate rose from 4.1 per cent in early 2008 to 5.8 per cent by mid 2009. The underemployment rate rose from 5.9 per cent to 7.8 per cent. Close to half a million extra people either had no work or not enough. If that’s not “going backwards,” what is?

On the national accounts’ bottom line – the trend measure of output, or gross domestic product, or GDP, per head– Australia went backwards for three consecutive quarters. The total fall was less than 1 per cent, whereas in Greece, so far, the slide has been 25 per cent. But our economic performance clearly receded, which is why it seems to me a recession.

But it is what followed that really matters.

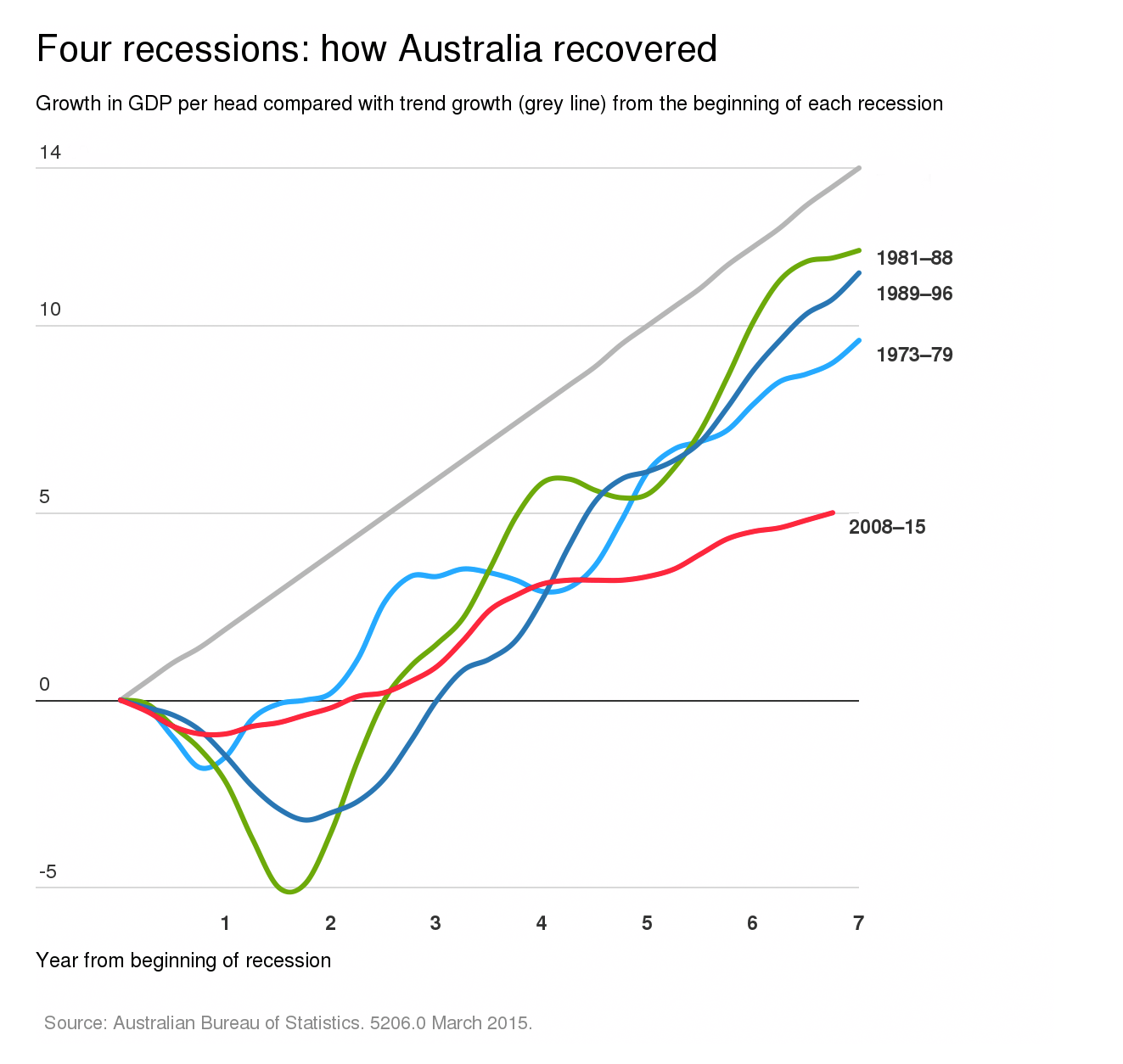

As the graph shows, this downturn, although the shallowest since the 1974–75 recession that doomed Gough Whitlam, has been followed by the weakest recovery Australia has seen since quarterly national accounts began in 1959.

The latest national accounts, those for the March quarter, show that since the pre-GFC peak in June 2008, our output per head – a pretty rough measure of economic living standards, but the best we have – has risen just 5 per cent over a period of almost seven years.

That is less than half the average growth recorded in the same period during and after the previous three recessions. Back in the Fraser years we thought the recovery was hardly worth the name, yet at this stage of that revival, GDP per head was already 9 per cent above its pre-recession peak.

After the 1980s recession, GDP per head had recovered by this point to almost 12 per cent above its pre-recession peak. Even the 1990s recession, which was protracted by poor policy decisions, saw output per head up 10.75 per cent by this time.

Over the thirty-five years before the GFC, despite three recessions, Australia’s output per head grew on average by 1.9 per cent a year. Since the GFC, almost seven years now, it has averaged growth of just 0.7 per cent. That is a sharp change.

But hasn’t Australia grown faster than just about any other developed country over the past few years?

Nope, that’s a well-recycled claim, but it’s a myth.

It is true that Australia was one of just a handful of developed countries to record positive growth in 2009, yet the economy grew less (1.6 per cent) than the population (2 per cent). Our living standards still went backwards.

Because our population keeps growing far more rapidly than most, ministers and officials usually focus on the raw growth figures, not the per capita ones. Why? Because we look much better that way, and to the sales team, presentation matters more than performance.

The International Monetary Fund estimates that between 2007 and 2014, Australia’s per capita GDP grew 6 per cent, which puts us just tenth among the thirty-six countries the IMF groups as “advanced economies.” You’d rather be tenth than twentieth or thirtieth, but we’re not world leaders.

The East Asian tigers were way out in front: Taiwan’s per capita output grew 21 per cent in that time, and South Korea’s 20 per cent. Even Germany, in the heart of the eurozone, marginally outpaced us, its output per head growing 6.4 per cent.

Similarly, Australia’s unemployment rate of 6 per cent is around the middle of OECD countries: equal fourteenth out of thirty-four members. Among the larger Western economies, we are actually in the worst half for unemployment: it’s 5.5 per cent in the United States, 3.3 per cent in Japan, 4.7 per cent in Germany, 5.4 per cent in Britain, and 3.9 per cent in South Korea.

In the southern German states of Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg, which together have a population similar to Australia’s, unemployment is now less than 3 per cent. Don’t let anyone tell you that we have full employment when unemployment is 5 per cent.

Our employment-to-population ratio is a little better: 71.6 per cent of Australians aged fifteen to sixty-four have a job, the twelfth best of the thirty-four OECD countries. But that is partly because of our extraordinarily high rate of underemployment – what the OECD terms “involuntary part-time employment.”

The recent OECD Employment Outlook 2015 shows Australia in 2014 had the fourth highest underemployment rate in the OECD, 8.6 per cent, behind only the disaster cases of Italy, Spain and Ireland. It is stunning that 11.6 per cent of all women with a job, or one in nine, were forced to work part-time because they could not find full-time work.

We escaped the GFC more lightly than most Western countries. But almost seven years on, we have experienced our most prolonged period of weak growth for eighty years. In the past three years, despite the population growing by 1.1 million, or 1.6 per cent a year, our GDP growth has averaged just 2.4 per cent, way below the 3.5 per cent we might have expected with such rapid population growth in the pre-GFC era.

Is that why Reserve Bank governor Glenn Stevens warned last week that our “normal” growth rate might be lower now than it used to be?

Possibly. Frankly, I’m not sure what he meant. The speech appeared to me and others to make the case for all actors in the economy – politicians and others – to focus on the need to lift our rate of productivity growth. But in question time, he declared himself optimistic about future productivity gains.

The speech approached the issue via an apparent anomaly in the statistics. In the past year the labour market seems to have picked up, with employment up sharply and unemployment down slightly, even though GDP growth has been coughing along at little more than 2 per cent growth. How can this be?

The Guv posed four possible explanations:

- The jobs and unemployment figures might have overstated the real strength of the labour market.

- The GDP figures might have understated the real strength of the economy.

- Our unprecedented low wage rises may have encouraged business to hire more workers despite the weak economy.

- Something has happened to lower our potential growth rate.

Most of his speech focused on the last option, but we should not rule out the first two as likely contributors.

First, anyone addicted to studying the labour force figures will know that they tend to move in surges: one year will record what seems like unrealistically high jobs growth, the next year it will seem unrealistically low. From 2011 to 2014, the figures showed three years of very weak jobs growth; maybe the data understated the reality, and some of the jobs created in those years have shown up in the figures just now.

Second, national accounts junkies know that the Australian Bureau of Statistics revises the growth figures up more often than it revises them down. At one point, it almost revised away the 1990–91 recession. It wouldn’t surprise me if it concluded that our growth rate over the past year was a bit higher than the 2.25 per cent shown in its March accounts.

Stevens’s third possible explanation – that employers are taking on more workers because of low wage rises – seems unlikely. Three-quarters of Australia’s GDP growth is now coming from exports, mostly mining exports, which employ few workers. The bulk of us work in the domestic economy, and domestic demand grew by just 0.6 per cent in the past year. While consumer demand is doing better, there's not much incentive to hire.

But our GDP growth per head since 2008 has been less than half of its traditional pace. Does that mean our sustainable growth rate has changed?

Possibly. Economic growth is produced by increasing productivity and/or increasing the total working hours of the population. Since the GFC began almost seven years ago, total working hours have grown just 0.7 per cent a year, compared to an average of 1.75 per cent over the previous thirty years. That almost exactly matches the slowdown in growth in GDP per head.

The reverse has happened with labour productivity. Since the GFC, the value of output produced by each working hour has grown by 1.7 per cent a year, an increase on its long-term average of 1.5 per cent.

The contrast is sharpest if you exclude sectors where our output is mostly not sold on the market – healthcare, education, government, etc. Since the GFC, hours worked in sectors competing in the market have grown just 0.3 per cent a year, whereas output per working hour has swollen 2 per cent a year. Work intensification? You bet, and that’s why Glenn Stevens said labour productivity is not a long-term problem. He’s right, but it makes it hard for this little head to understand what his real point was.

Population growth is not the issue. Since the GFC, it has averaged a bustling 1.7 per cent a year, causing problems for the four cities where most of it is happening, but not for the economy. It has slowed recently, but is still above its long-term average of 1.3 per cent.

An ageing population is gradually slowing the potential growth of the labour force, but there is still lots of spare capacity, an immigration tap that can be turned up if needed, and increasing willingness by older people all over the Western world to keep on working. (In the past decade, despite the shortage of jobs, the number of over-sixty-fives in the workforce has more than doubled from 178,000 to 419,000.)

It was an unusual speech for Stevens, who has spent most of his long period as governor trying to avoid saying anything that treasurers might see as unwanted advice on how to do their jobs better. Possibly he is becoming bolder before his retirement next year, or possibly, like the rest of us, he is just fed up with the degradation of public debate under the Abbott government, and its aversion to doing anything politically hard to achieve long-term reform.

The bottom line is that we could be doing a lot better. I would just respectfully ask the Guv to be a bit clearer about exactly what we need to do better. •