Does “stopping the boats” count as a success? Boats carrying asylum seekers to Australia are being returned to Indonesia; asylum seekers intercepted on their journey are being detained and processed offshore; asylum seekers who pass through Indonesia are being denied any chance of resettlement in Australia even if they are found to qualify as refugees. Together, these measures have reduced the incentives for asylum seekers and refugees to depart from Indonesia on a boat bound for Australian territory.

The extent to which this seems like a positive development depends on what we ignore. Offshore detention clearly comes at a staggering human and financial cost, and the ongoing needs of the asylum seekers and refugees who remain in Indonesia are far from resolved. Indonesia now faces the challenge of responding to the long-term presence of asylum seekers and refugees, rather than merely responding to their transit through the archipelago. Given the degree of internal displacement and economic and social pressures within Indonesia, the plight of asylum seekers and refugees may not be a high priority. Government minister Tedjo Edhy Purdijatno’s recent threat to release “a human tsunami” of “illegal immigrants” into Australia nevertheless suggests a willingness to exploit the issue (and Australia’s sensitivity about it) for strategic gain. There are good reasons, in other words, to doubt that the “stop the boats” policy has been a success.

At the end of 2014, 4270 refugees and 6916 asylum seekers were registered with the Jakarta office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, an organisation whose resources have been stretched, worldwide, by the largest number of people in refugee-like situations since relevant data started being collected. UNHCR’s Jakarta office is chronically underfunded and Australia’s policy changes have added to the pressure by reducing the exit options for refugees and asylum seekers in Indonesia either by boat or via resettlement. According to the UNHCR, the waiting period between initial registration as an asylum seeker and a first-round interview ranges from eight to eighteen months. Further interviews are usually required to determine refugee status. For people found to be refugees, the wait then continues until a country willing to offer resettlement is found. The longest wait-time we are aware of is eleven years in total.

During that period, asylum seekers and refugees are expected to find and pay for their own accommodation using their own savings or remittances from family and friends. They are not permitted to work in Indonesia. The latest figures show that 1123 children registered with the UNHCR were either unaccompanied or separated from their parents during the journey, an increase of 40 per cent from the previous year. The UNHCR can offer shelter to just eighty of them. More broadly, the organisation’s budget can provide direct financial support to only 340 people (equivalent to 3 per cent of the total number of registered asylum seekers and refugees in Indonesia). Recipients are chosen according to criteria of vulnerability, with preference given to unaccompanied minors and women at risk. The UNHCR is well aware of the inadequacy of its budget: with dozens of asylum seekers and refugees sleeping in the alleyway in front of the entrance to their workplace, staff of the Jakarta office are reminded every day. Boys as young as fourteen can be found sleeping in the street and in mosques at night.

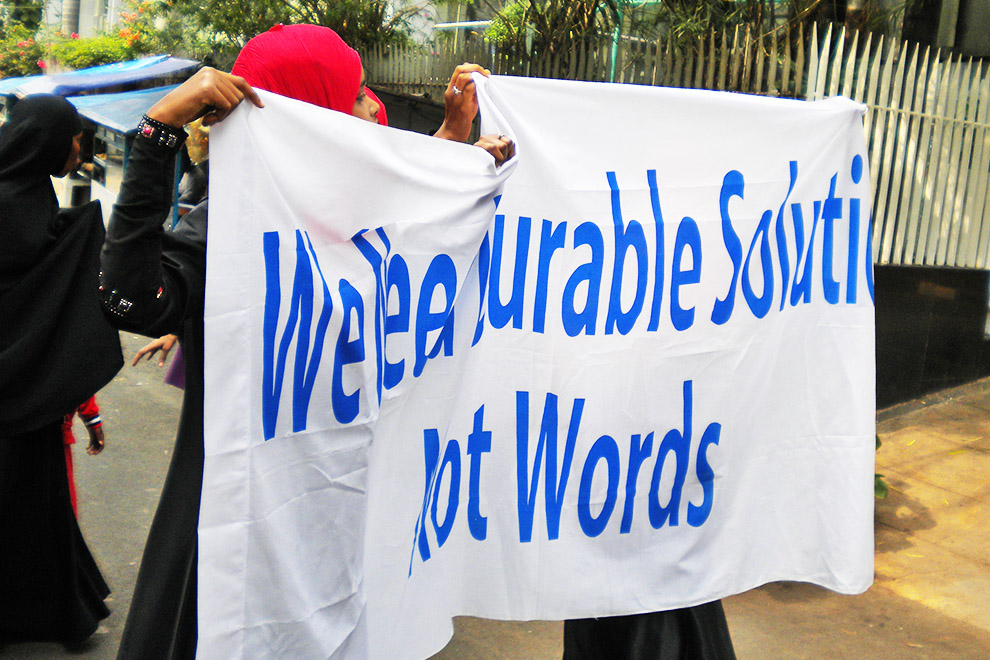

Daily reminder: asylum seekers waiting in an alleyway next to the office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees in Jakarta, where some of them spend the night sleeping on cardboard.

Although some refugees and asylum seekers are able to pay to enter the private rental market, landlords are either reluctant to rent to outsiders or do so at inflated prices. In Puncak, an hour’s drive from Jakarta, we met asylum seekers who were fearful of leaving their houses at night. In the past, they had been beaten and robbed by locals on the street, or extorted by others posing as authorities. Similar stories have been reported in the Indonesian press. In August 2014, for instance, an elderly Afghan man accompanied by his wife and children had his nose broken by a group of youngsters in the nearby town of Cisarua. The asylum seekers with whom we spoke felt powerless to report incidents to police, whom they suspected of extorting asylum seekers in general. “We cannot punch back; we cannot do anything,” they told us. “We have to let them do whatever they want to us.”

The only other avenue of assistance for asylum seekers and refugees is through the International Organization for Migration. Since 2001, the IOM has provided various forms of “care” to refugees and asylum seekers in Indonesia under the terms of a tripartite agreement with the Australian and Indonesian governments, funded largely by Australia. The organisation funds community housing projects for recognised refugees and vulnerable asylum seekers in several locations, and provides a stipend of RP1,200,000 per month to those under its care (just under half of the average income in Jakarta). As of 31 January 2015, the IOM was assisting 7678 people. Of these, 2874 were based in community housing projects and 2237 in temporary interception sites; the remaining 2567 were immigration detainees whose food and essentials were billed to the IOM by Indonesia and for whom the IOM provided occasional language classes, sports activities and other forms of distraction. The cost of food alone for the current cohort of detainees amounts to approximately A$11,500 per day.

Eligibility for IOM assistance is not automatic. The necessary referral from Indonesian immigration authorities normally occurs only once a person has been detained or has been released from detention. Officially, registered asylum seekers and refugees in Indonesia are only detained if they are found in areas designated as off-limits (ports, beaches or transport hubs, for instance) or if they fail to comply with specific reporting conditions. In reality, they have been subject to the threat of arbitrary detention by corrupt officials who see an opportunity to extort money from them.

Previously, asylum seekers and refugees paid bribes to avoid detention. Since late 2013, though, destitute asylum seekers and refugees have begun to arrive at detention centres, or approach immigration officers, seeking to be detained. With private resources exhausted, this is the only way to obtain basic food and shelter and a referral to the IOM. Immigration officials in Balikpapan, Kalimantan, for instance, have reported that they receive a handful of people every week who ask to be admitted to the immigration detention centre.

Most of the detention centres are terribly overcrowded. Indonesia has a total capacity of 1300, but in March 2015, according to immigration authorities, the number of detainees reached 2552. Conditions in some centres are worse than others, dependent largely on the resources available and the discretion of the officer in charge of each centre. Their reputations have spread quickly and asylum seekers opting for detention appear to make well-informed decisions about which centre to choose. In some cases, detainees sleep in the corridors, while those who can afford to pay a little extra might gain a spot in an overcrowded room. Both IOM staff and the Indonesian Human Rights Commission have at times been denied entry to certain detention centres. In others, detainees are free to receive visitors, use mobile phones and even make trips to the ATM or the supermarket.

In some cases, local immigration authorities have sent away asylum seekers attempting to self-report for detention. As a consequence, a perverse market in brokerage and bribes has evolved. According to those we interviewed, it can now cost as much as US$500 to be “accepted” into detention. Other fees change hands for information about better and worse detention centres, to facilitate domestic travel to more favourable centres, or, once an asylum seeker is in detention, to transfer to a less crowded facility. Immigration authorities bill the IOM for the costs of transfers.

For asylum seekers in detention, a referral into the “care” of the IOM is at the discretion of immigration authorities. Single male asylum seekers are unlikely to be released into the hands of the IOM before they have been recognised as refugees. Female asylum seekers, and those with families, may be released earlier. In January 2015, eight births took place in detention. For those released into the IOM’s community housing projects, conditions are usually much better, but not without difficulties. In 2012, for example, community housing in Puncak prompted complaints from local residents, fuelled by concerns about cultural differences, alcohol consumption and allegedly predatory sexual behaviour. When locals heard nothing from the central government in response to their complaints, vigilantes threatened to raid the housing area themselves. The threats prompted many asylum seekers to leave of their own accord; others were relocated by the IOM to temporary accommodation on the outskirts of Jakarta. Given these tensions, Indonesian authorities are increasingly concerned to organise housing for asylum seekers that allows for minimal contact with Indonesian locals.

The acute shortage of accommodation has caught the attention of industrious insiders. Anecdotal reports suggest that among those building private accommodation and renting it to the IOM are former immigration officers and local heads of police. When we visited one such custom-built two-storey shelter two hours from Medan, Sumatra, it appeared from the outside to be in good condition. On the inside, it was unbearably hot, with only sporadic ventilation and no air-conditioning. A malfunctioning generator caused frequent blackouts and an open sewerage system offered a fertile breeding ground for mosquitoes. Nevertheless, a room for two people earned the property owner RP100,000 a night, a little less than the cost of a cheap backpacker hotel. With seventy residents, the owner could earn over A$10,000 a month in rent. Partly in response to the difficulties of the private rental market, and partly as a means of maintaining greater control, immigration authorities have started to use empty state-owned dormitories and shelters as temporary accommodation.

Industrious insiders: custom-built shelters rented by the International Organization for Migration near the city of Medan, Sumatra.

None of the available options for accommodation – detention centres, private rentals or state owned dormitories – is likely to be sufficient for demand. Three national ministers recently resurrected a mothballed plan to house asylum seekers and refugees on an uninhabited island in the eastern part of the archipelago while they wait to be processed by the UNHCR. The plan reflects a degree of nostalgia for the former detention island of Galang, near Singapore, which served as a transit point for Indochinese refugees awaiting resettlement from the late 1970s to the mid 1990s. The idea of a “new Galang” was first circulated some years ago, but was set aside twice for funding reasons and a lack of support from Canberra. According to Indonesian sources, the regional immigration authorities in the province of East Nusa Tenggara have already acquired 5000 square metres of land on the island of Sumba for potential development. Sumba is one of the poorest and most isolated areas in Indonesia. It is also less than 700 kilometres from the Australian coast. The Australian government feared that a shelter on the island would attract people smugglers and preferred an island on the western side of the archipelago. In either case, the relocation of asylum seekers to a remote island for an indefinite period is unlikely to yield an effective system of protection.

Indonesian authorities are attempting to grapple with what has become a permanent or semi-permanent condition of transit for asylum seekers and refugees. Those who can’t return to their home countries for fear of persecution are also unable to secure any kind of dignified life as they wait indefinitely for potential resettlement. Stuck in cycles of bureaucracy, corruption and destitution, their plight reveals one of the unseen impacts of the focus on “stopping the boats.” The larger challenge of establishing a sustainable regional mechanism for refugee protection remains. •