Australia needs the best and brightest in teaching. But it won’t happen if dangerous myths about teachers’ pay go unanswered. In the past few weeks we’ve been told, yet again, that Australian teachers are among the highest-paid in the world, this time based on new figures from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. It’s a misleading claim that damages teacher quality and therefore student performance.

The right way to look at teachers’ pay is to ask whether it is high enough to attract the people we want and need into teaching. In Australia the answer is no.

Australia is a rich country. Our incomes are high in comparison with many other countries. But our education system is competing with other industries to attract the best talent.

A more meaningful international comparison is to look at how teachers’ pay lines up with the incomes of other professionals in their own country. While Australia’s pay for young secondary teachers relative to other professionals stacks up well internationally, our pay for secondary teachers in their mid-thirties and their forties is below the international average.

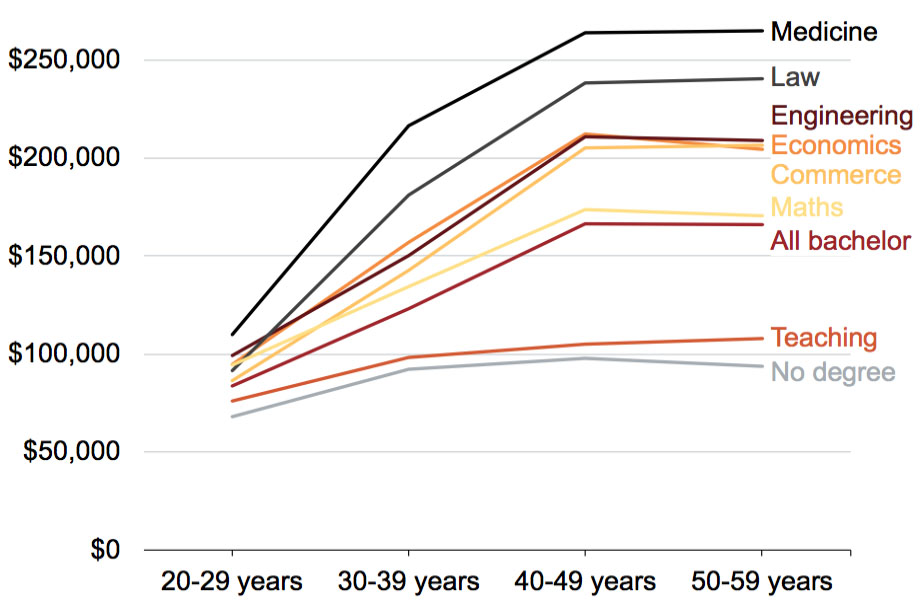

Chart 1. Teachers quickly fall behind their peers in other professions

Total yearly personal income of full-time workers holding a bachelor degree, by field of study, 2016, at the eightieth percentile of the income distribution

Notes: Includes people who studied a teaching degree but now work as principals or outside teaching. Four-digit fields of education chosen because they have the highest median ATAR. “No degree” includes all levels of education below bachelor.

Sources: Australian Bureau of Statistics; Grattan analysis

In other words, Australia’s young teachers are paid well, but the pay scale is flat. Teachers’ pay at the top is only 1.4 times as much as their starting salary, below the OECD average. An Australian classroom teacher’s pay stops rising within ten years, whereas the incomes of his or her peers in other professions keep rising well into their thirties and forties.

Chart 2. Since the 1980s, teachers’ pay has fallen well below pay in other professions

Average teacher salaries as a percentage of all professionals, 1986 to 2018

Notes: Salaries measured as the average weekly cash earnings of full-time non-managerial adult employees. In 2006 the ABS started including salary-sacrifice income and changed the definition of “professional.” For years 2010–18 aggregate incomes for all professionals were not available, and so they were calculated using the weighted average of all professional occupations. The weights were derived from the number of full-time workers in each occupation and gender category in the 2016 census.

Sources: Australian Bureau of Statistics; Andrew Leigh, “Teacher Pay and Teacher Aptitude.”

But average pay is not the only factor. More important — especially for attracting young high achievers — is the potential to earn a very high income if you do a good job. Bright young Australians have a good chance of earning a high income in many professions, but teaching is not one of them. More than a third of engineering or commerce graduates in their forties working full-time earn more than $3000 a week ($156,000 a year). But for graduates with a teaching degree, that share is only 2.3 per cent.

A Grattan Institute survey of almost 1000 young high achievers (aged eighteen to twenty-five and with an ATAR of 80 or higher) shows that 70 per cent are open to becoming teachers. But university enrolment data show that, when it comes to the crunch, only 3 per cent of high achievers actually choose teaching for their undergraduate studies. Our survey shows that a major barrier is teachers’ pay.

Australia’s young bright people are being asked to make a big financial sacrifice if they choose teaching as their career. They know they will be staring down the barrel of a lifetime of pay much lower than that of their classmates who choose degrees such as engineering, science and law.

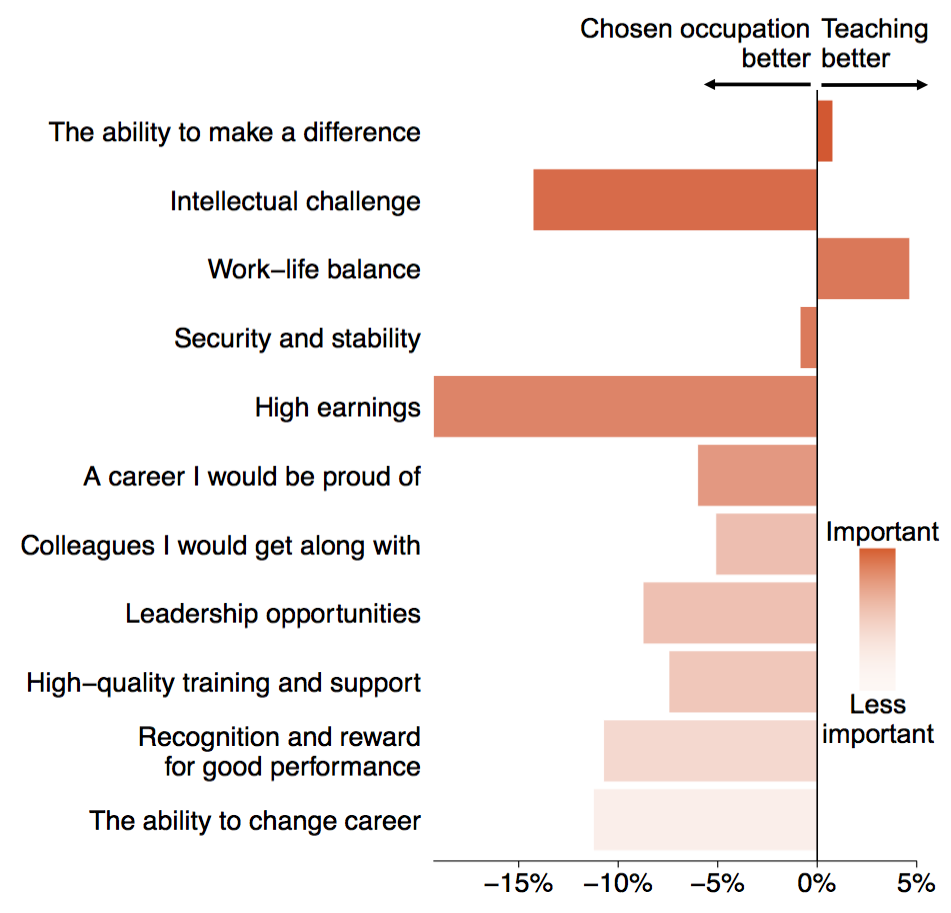

Chart 3. High achievers say teaching falls short on intellectual challenge, and pay

Young people who state that a career in teaching is more likely to provide a given attribute than their chosen occupation

Note: Career attributes are ordered top-to-bottom from most to least important. The data in the chart show the difference (teaching minus chosen occupation) in the percentage of respondents who answered that a given career was likely or very likely to provide each attribute.

Source: Grattan Institute survey of high-achieving young Australians.

This is a big problem. Teacher “smarts” matter. Evidence shows that people with strong academic records do a better job teaching in the classroom. Yet over the past forty years, teachers’ pay has been declining in Australia relative to other professions, and with it fewer bright young people have chosen teaching as a career.

The fact that only 3 per cent of high achievers choose to study teaching compares very unfavourably with 19 per cent for science, 14 per cent for health, and 9 per cent for engineering. Over the past decade, high achievers’ demand for teaching fell by a third — more than for any other undergraduate field of study.

Australia’s school education system is not in a good place. Our kids are falling behind. In international tests, the typical Year 9 student performs at a much lower level than a similar-age student in 2003 — lower by twelve months in maths and nine months in reading.

We can never know for sure what is causing our students to fall back, but it’s difficult to ignore the fact that Australia’s test-score decline has coincided with the retirement of many of the teachers who were recruited when salaries were much more competitive with other professions.

If Australia is to catch up, bold action must be taken. A new Grattan Institute report, Attracting High Achievers to Teaching, proposes a $1.6 billion reform package for government schools to double the number of high achievers who choose to become teachers. It would increase the average ATAR of teaching graduates from 74 to 85 within the next decade.

The package includes $10,000-a-year scholarships for high achievers who take up teaching, and new career paths for leaders of the profession, with pay of up to $180,000 — about $80,000 more than the current highest standard pay rate for teachers.

If governments were to implement this blueprint, it would send a strong message to Australia’s best and brightest: if you want a challenging career where expertise is paid accordingly, choose teaching. In the long term it would pay for itself many times over, because a better-educated population would mean a more productive and prosperous Australia. •