Has any government activity been as closely scrutinised as the eight-year-old Murray–Darling Basin Plan? One of the most ambitious natural resource management schemes in the world, the plan was intended to claw back water from irrigators and put an overallocated river system onto a sustainable footing. It has been causing political pain since the day it was released.

At the end of this month, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission will issue an interim report on water markets. The government is also due to release the findings of an independent panel assessing the social and economic impacts of the plan, which is already with the minister, Keith Pitt. Meanwhile, the Australian National Audit Office is looking into water buying by the Commonwealth, and the NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption is examining allegations of corruption and water theft in the northern basin.

Each inquiry is likely to conclude that it lacked some of the information necessary to reach firm conclusions. And this, correctly understood, is a national scandal.

What experts describe as all-pervasive and “nightmarish” flaws and inconsistencies in the data, combined with manipulation and special pleading, are fuelling the toxic politics of the Murray–Darling. Already, it is beginning to have an impact on the jockeying ahead of the 2022 federal election.

One of the architects of the Murray–Darling Basin Plan and the water-trade system is Mike Young, who holds a research chair in water and environmental policy at the University of Adelaide. Having worked with the then water minister Malcolm Turnbull when the plan was being devised, he now says the data on water is so flawed that it poses “serious problems” for managing the basin.

“You don’t know which data systems to trust,” he says. “There is not even agreement on the systems… and if you’ve got flawed data and you’re trying to manage the system, you’ve got a serious problem. It’s nightmarish.”

Adelaide-based natural resource consultancy Auricht Projects has assembled data from a range of sources on climate, inflows, trading and crop water use, and in the process found numerous irregularities in government datasets. These have resulted in mistakes and a lack of consistency not only in the work of lobby groups and consultants but also in official reports.

Some errors are minor, says managing director Chris Auricht, but others have led to “misinformation and myths… that allow for rent-seeking and cost-shifting.” Some reflect a failure, including by highly paid consultants advising government, to acknowledge the assumptions behind the data or recognise how a dataset has been updated or modified over time.

Of even more concern, the water-trade data provided by the Bureau of Meteorology’s national water markets dashboard is not always internally consistent. The dashboard, says Adam Loch of the University of Adelaide, is the equivalent of the Australian Stock Exchange for water, and should be the gold standard for information on water trades.

With $3.7 billion of water trades in 2019–20, according to the bureau data, it’s a huge industry, and that means data problems can have big implications. According to Loch, discrepancies of up to $100 million become evident depending on how and when you dip into the data, with no explanation as to why.

The multifaceted water-data problem has been highlighted in recent months by the work of the interim inspector-general of Murray–Darling Basin Water Resources, Mick Keelty. Keelty, a former commissioner of the Australian Federal Police, was appointed commissioner for the northern basin as part of the political management of Four Corners’s 2017 revelations of water theft. He was touted as a “tough cop for the basin.”

Since then, his role has expanded well beyond enforcement and compliance, leading him into areas where even the experts struggle. The then water minister, David Littleproud, gave him his current basin-wide role last year. It sits at the intersection of water data and politics but, one suspects, tends to lean into the politics.

Then came the Can the Plan protests of last December, led by NSW irrigator Chris Brooks. About 1000 people and one hundred trucks converged on Parliament House in Canberra, protesting at the fact that they’d had no allocation against their water licences for two years running.

Brooks, a former chief executive of Glencore, the giant global commodities trader, is one of rural Australia’s most aggressive and effective political players. His wealth is built on resources and land, and he has duked it out at the highest levels of politics.

Spurred by anger over the Murray–Darling Basin Plan and what he understood to be its impact on his region, he spearheaded and financed successful campaigns by Shooters, Fishers and Farmers Party candidates to win National Party seats in the last NSW election. He was also behind the Voices for Farrer campaign, in which former Albury mayor Kevin Mack grabbed votes from the Liberal incumbent, Sussan Ley, in the 2019 federal election.

During the Can the Plan rally, Brooks was called in to speak to Littleproud. Mick Keelty was there, too. In an apparent piece of ad hoc political management, Littleproud told Brooks that Keelty would immediately investigate the way states share water.

It was an odd announcement, not least because it was well outside Keelty’s area of expertise. It also came as a surprise to the head of the Murray–Darling Basin Authority, Phillip Glyde.

Brooks, addressing the protesters outside parliament, pronounced it a win. He and his supporters put about the idea that Keelty’s review would lead to more water for the irrigators of the NSW Murray — which would have been a perversion of policy and a massive compromising of the Murray–Darling Basin Plan.

One of the Can the Plan organisers, Darcy Hare, told rural press outlets that Keelty would “find buckets of water that are locked away and not utilised due to archaic rules.” Brooks said, “We have turned the corner; the future is looking brighter. I am hoping we now get a better and fairer allocation of water in the new irrigation season.”

Keelty’s report was released in April, and at first it seemed that the integrity of existing policy had held and Brooks had failed. For those in the know, it contained few surprises. No spare water was lying around to be reallocated, and the reduction of inflows was the main reason for reductions in water allocations. Brooks and his fellow protesters had no water, whereas their Victorian neighbours on the other side of the river did, simply because of different state government approaches to allocations. New South Wales was running the system hard, with less in reserve to cope with dry seasons.

So why did the southern NSW irrigators believe that “buckets of water” were “locked away”? The answer comes back to data, and to work by an agricultural consultancy called RMCG and its principal, Rob Rendell. RMCG has done work for the dairy and rice industries, both of which have been losers during the drought because of cuts in allocations and rises in water’s price.

Rendell’s core assertion, backed by extremely complex calculations using contested data, is that years of decisions about how carryover water, conveyance water and evaporation are calculated have resulted in a short-changing of NSW and Victorian Murray River irrigators. (Carryover water is held in public storage by irrigators who don’t use all their allocation in a single year. Conveyance water is the amount calculated as necessary to run the river.)

Rendell says that his calculations reveal “underused” or “unused” water in the system, leading to flows into South Australia greater than the amounts agreed under the Murray–Darling Basin Plan. Keelty dealt with this allegation very briefly in his report, noting that the Murray–Darling Basin Authority was investigating the allegation and recommending that the results be clearly communicated.

Weeks later, though, the overheated world of water was rocked when Keelty attended a webinar held by Adelaide’s Stretton Institute on 26 May and gave the ”underused water” narrative another run, using strong language to attack the Murray–Darling Basin Authority. According to Keelty, the authority had initially told him that the “underused” water amounted to about fifty gigalitres of water each year for seven years, making a total of 350 gigalitres. After he queried its figures, it “readjusted” to 350 gigalitres a year for each of the seven years.

That’s quite a readjustment. To put it in perspective, as Keelty noted, the Can the Plan protesters had been after just 200 gigalitres to allow them to plant an autumn crop.

Keelty said he had hoped, at first, that the 350 gigalitres a year might be allocated to the southern basin irrigators Brooks represents, or alternatively “put on the table” at a ministerial council meeting with a view to reducing the amount of water going to South Australia. In other words, if this water was really sloshing around the basin, available to be reallocated, it could transform the dynamics and the politics.

But Keelty already knew it wasn’t that simple. The water couldn’t easily be reallocated; it was locked up in many different locations. Rendell, on the other hand, told me that he believed “some of it” could be reallocated.

Keelty said at the Stretton Institute that his lack of faith in the authority’s figures had led him to consider recommending that it should be split up, as a previous Productivity Commission report had recommended.

“If you trust the Reserve Bank to help us through a global financial crisis… we’re going through a similar crisis in terms of water and water availability,” he said. “And we need to have confidence in the organisation that takes us through. You’ve heard me saying here tonight that I’m worried about some of the data that the MDBA has produced.”

The idea of “underused” water was contested during the webinar by Mike Young, who said the term was a misnomer. At most, the water might have been misallocated, he said. The idea it was simply flowing into South Australia and then out to sea was wrong. The Murray Mouth still needed dredging to remain open, even though avoiding the use of this simple indicator of system health was one of the main aims of the Murray–Darling Basin Plan.

Young also referred to concerns among “colleagues of mine” that some of the data in the Keelty report was simply incorrect. He was talking about Chris Auricht and his team.

So why had Keelty changed his tune in the weeks between the release of his report and the Stretton Institute appearance? After initially saying he may be available to talk to me about these matters, his office fell out of touch. We are left to join the dots.

Not surprisingly, Brooks and his supporters were bitterly disappointed by the failure of the Keelty report to find more water. “We went to Canberra and we were disarmed by Keelty,” Brooks told the Deniliquin Pastoral Times. “He seemed to say all the right things, but this report is disappointing. We’re all shattered.” The NSW government, which is increasingly sensitive to Brooks’s concerns, also slammed the report.

In the same week that Keelty addressed the Stretton Institute, a disappointed Brooks announced that he would form his own “well-resourced” political party and stand “very credible candidates” in four government-held federal electorates: Mallee, Nicholls, Farrer and Riverina. ABC election analyst Antony Green has said that minor parties and independents stand a real chance of splitting the National Party vote in these seats.

This was the context in which Keelty began to pick up the underused water narrative. At the Stretton Institute, he described Rendell and RMCG as having presented him “a series of cogent, quite unemotive analyses that there was anything in the order of 900 gigalitres of water that was not accounted for properly in the system… So we met again with them in Melbourne… and they had adjusted their calculations.”

Again, quite some readjustment.

Asked to respond to Keelty’s criticisms of its figures, the Murray–Darling Basin Authority’s acting executive director for water resource planning and accounting, Peta Derham, said in a statement that work continued to analyse the “patterns of underuse,” and “targeted consultation” was taking place with stakeholders. As I understand it, the authority has identified “underuse” — although nobody seems entirely clear what that term means — but doesn’t understand the cause, and is speaking to growers to get more information.

But the authority insists there is no spare water. Any water not used is put back into the “consumptive pool” and reallocated.

The real scandal, as the wild variations in figures and the difficulties of finding an answer attest, is that the data isn’t up to the job of determining who is right. Or not in a way that can be scrutinised and assessed.

So is there “underused” water? You might think it would be a simple question. Water use in the southern basin is closely metered — unlike in the northern basin, where meters are often dodgy or missing.

We know how much rain there is. We know how much water is extracted. And since the Murray–Darling Basin Plan was legislated in 2012, the cap-and-trade system has included an agreed “sustainable diversion limit” on how much water can be taken, both in the basin overall and in each catchment.

Under Labor, water was bought back for the environment. Under the Coalition, the emphasis has been on introducing taxpayer-funded “efficiency measures” implemented on private farms to claw back water for the environment.

But the underused water allegations reveal how little we really know about how much water exists, who is using it and, ultimately, whether the Murray–Darling Basin Plan is working. In fact, the world of water data leads you down a rabbit hole — or perhaps a plughole is a better metaphor. Complexity and the lack of transparency lead to a lack of scrutiny. And, in an atmosphere devoid of trust, that causes political problems.

This is the context in which Chris Auricht and his colleagues, Adam Loch and David Adamson, both of the Centre for Global Food and Resources at the University of Adelaide, have been tracking the data, using what they say is information sourced from both government and industry sources, crunched and analysed. In a full disclosure, Auricht, who has worked with the World Bank and the United Nations on datasets, acknowledges he hopes to win work helping to sort out the data mess. “We have a strong track record in this area and think we are well placed to do that.”

He says that inconsistencies in the way states collect data, together with a lack of understanding of the datasets involved, have led to “what could be termed… misinformation and fake news.” Added to this, he says, is a lack of care by those who use the data. Important inconsistencies in the way states collect and present data mean that lobbyists can choose whichever version fits their narrative.

Auricht says he has found contextual issues and potential errors in almost all the key recent government reports on the Murray–Darling, including Keelty’s, and in the submissions and reports of key lobby groups. He is reluctant to call them out in public — “I’m not interested in pulling anyone’s pants down” — but he is deeply concerned about the implications.

It means, he says, that almost any question you might ask about the management of the Murray–Darling is impossible to answer with confidence. Chris Brooks and his supporters can run an election campaign alleging their region has been dudded, and it is almost impossible to say with certainty whether they are right or wrong.

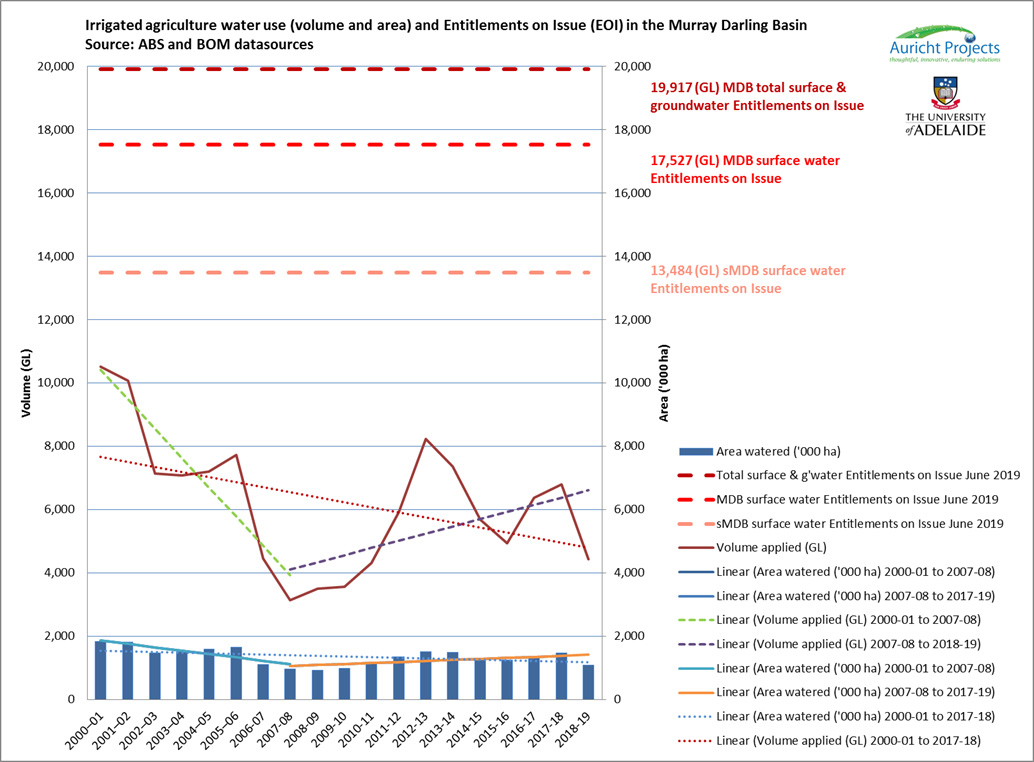

There is a bigger picture. This graph, provided by Auricht and the Adelaide University researchers, is drawn from publicly available data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics and the Bureau of Meteorology. The same data has been used by some of the current inquiries into Murray–Darling Basin matters, but they presented the information differently, and without the potentially devastating trend lines.

The graph reveals that despite the Murray–Darling Basin Plan — which is all about saving water for the environment — the trend over the past twelve years, regardles of annual variability, is an increase in the volume of water applied for irrigation.

Granted, the overall picture since 2001 is a decline — but that relates to the period before the Murray–Darling Basin Plan was legislated in 2012. As well, the closure of many irrigation businesses — dead and torn-up trees and grapevines litter the Riverina and Sunraysia districts — has been more than outweighed by new developments.

It’s not as simple as the plan failing to peg back water use. How much water is used is naturally driven by water availability, with the millennium drought hitting hardest in 2007, creating a low base for increases since then, and a surge in water use in the flood year of 2012. Given this variability, it may be that thirteen years is too short a time from which to draw trends.

What is clear is that the passing of the Water Act in 2007 and the legislating of the Murray–Darling Basin Plan in 2012 has had no discernible impact on total water use for irrigation so far, despite the fact that water has been variously bought and saved for the environment. And, with a current basin-wide cap of 11,586 gigalitres, use can increase further before any breach.

The dotted lines at the top of the graph show the total current entitlements to water in the basin, and the southern basin, including irrigation, cities and towns, and the 2800 gigalitres being returned to the environment under the Murray–Darling Basin Plan. This shows that the system remains massively overallocated, says Auricht — or, to put it colloquially, “more tickets have been sold than there are seats in the water stadium. There is not enough water in the system to satisfy total entitlements.”

Some say this doesn’t matter. Taking a broad brush to great complexity, irrigators buy licences that are either high security, low security or — the most common — general security. They are then allocated a percentage of their entitlement in each growing season. Only in a very wet year, or following a wet year when storages are high, would people expect to get 100 per cent of their allocation. So it’s less a case of too many tickets having been sold, and more that we have sold a bunch of tickets that everyone agrees will never be used.

Asked to comment on this graph, the chief executive of the Murray–Darling Basin Authority, Phillip Glyde, said in a statement,

@@

We expect variability in water use from year to year within the limits set by the Basin Plan. Irrigators are using the water made available to them under allocation frameworks — that is their right and has ensured production can continue.

There has been an increase in water used in the past decade because people are accessing more of the water available to them, which is a factor of the overall dry conditions we have experienced. We expect irrigators to use more of their allocated water in dry years.

Water held in the dams after the 2010–11 and 2016 floods was called on by irrigators in subsequent years as it was almost the only water available to them. If conditions had been wet, use of water allocations would have tapered off as rainfall would have sustained crops instead.

@@

The idea that the overallocation doesn’t matter because licencees won’t ever get their full allocation doesn’t cut much mustard with the irrigators in South Australia, who stand to lose if Brooks persuades too many people that water is sloshing over the SA border, unseen and unaccounted for.

Chris Byrne is the executive director of Riverland Wine, which represents more than 900 grape growers. He says that if you have a ticket in the water game, you expect to be able to use it, and the continuing overallocation is the cause of the pressure on South Australia.

“When you can’t use your licence or you don’t get your full allocation, you look across the border and say, ‘Look, all that water going into South Australia. Why can’t I have an allocation?’… And that’s exactly what’s happening and that is behind the politics here.”

The chair of Riverland Wine, Brett Proud, agrees. “Local irrigators suffer nightmares over water markets and water security fears. Their ability to manage risk is limited due to a lack of confidence with current information. Unless the research is comprehensive, independent and the data analysis relevant to the risk management of water users, the vast sums of money spent so far will be of little use.”

The graph also shows that despite all the taxpayer-funded efficiency schemes, irrigators overall are applying water more intensively — more litres per hectare — than before the plan. Why? Auricht says his datasets point to many new almond plantations, initially funded under the tax-dodging managed investment schemes of the 1980s and 90s and now backed by big corporates.

Almond trees are thirsty, and the plantations are governed by research that precisely calibrates how much water is needed for a maximum crop. (The short answer is “more.”)

Another reason why more water is being used is likely to be a greater number of hot days. They will increase further, and inflows will fall, as a result of climate change and changes in land use. And, says Auricht, water markets won’t necessarily sort it out. In the face of high prices for water, irrigators have not accepted market outcomes, instead calling for ministerial intervention, demanding water be reallocated and insisting that water taken for the environment be given back to them.

Auricht says the real cost of unreliable data, together with political manipulation of that data, is that irrigators are not being encouraged to manage their risks, or given the tools to do so.

“That means their standard adaptation approach is always going to be seeking some form of government intervention or assistance, which is unsustainable. When water isn’t available in the future, they are not going to be ready, and will fail, with taxpayers having to pay the price via bailouts that shouldn’t have to occur.”

What should be done? The Murray–Darling Basin Plan was originally scheduled for review in 2026. Mike Young says it is clear that needs to happen much sooner. “The simple story is that someone needs to be given full responsibility for the production of datasets that are trusted,” he adds. “Trust comes from accuracy and careful revelation of assumptions and the nature of the estimates made.”

Keelty clearly agrees. He has spoken several times about the need for a “single source of truth” on water data.

In the meantime, if we ask whether the Murray–Darling Basin Plan is meeting its objectives, the hard answer is that it depends on which data you choose to look at, which consultant you have paid to help you make sense of it, and what you mean by success.

Beneath the plughole lies uncertainty, fake news and a looking-glass world in which truth is elusive. Another water academic, Quentin Grafton of the Australian National University, has described the implementation of the Murray–Darling Basin Plan as taking place in a post-truth world.

Its results will play out at the next federal election. •

Funding for this article from the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund is gratefully acknowledged.