THE party vote results of Saturday’s parliamentary election are now clear, though as is common in multi-party proportional systems, the final outcome will not be known until talks on the formation of government are complete. At the close of the provisional count on Sunday, just four of the twenty-one competing parties had cleared the 3 per cent threshold to be eligible for seats in the sixty-five-seat parliament.

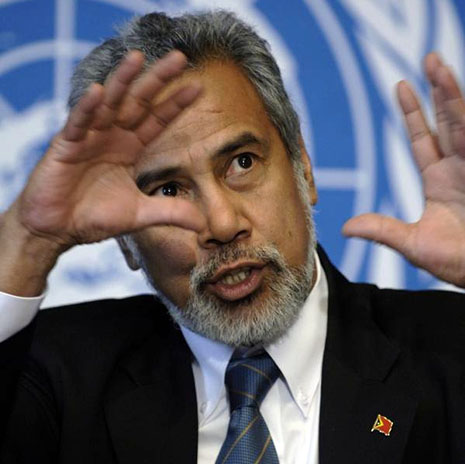

As expected, no single party gained an absolute majority of thirty-three seats. Nonetheless, prime minister Xanana Gusmao’s CNRT produced a dominant performance with 36.66 per cent of the national vote, followed by the current opposition Fretilin party with just under 30 per cent. The Democratic Party emerged as the new third party with 10.3 per cent of the vote, and Frente-Mudança, a small breakaway party from Fretilin, received 3.11 per cent. A new party, KHUNTO, with links to one of Timor-Leste’s martial arts groups, came close to qualifying for a seat with 2.98 per cent and will be hoping a recount finds them enough votes to get over the line.

The large number of small parties that failed to clear the threshold is significant. Their votes will be excluded in calculating proportional seat distributions, which will increase the number of seats flowing to the successful parties. With seventeen parties under the threshold this time, some 20 per cent of the vote will be ruled out. This means, for example, that CNRT’s 37 per cent vote share will bring the party closer to 45 per cent of the seats, putting it in a strong position to lead the next governing alliance. Unofficial calculations have CNRT on thirty seats, Fretilin on twenty-five, the Democratic Party on eight, and Mudança on two. The parties will be waiting for an official determination on seat numbers from the National Election Commission this week.

If KHUNTO were able to reach 3 per cent on a recount then it would receive two seats, with one coming from each of the two major parties. This seemingly small shift in the parliamentary carve-up might well be critical because, as we’ll see, the difference between Fretilin’s having twenty-four and twenty-five seats could prove a significant influence in the coming parliament. For this reason, caution is required in reading the provisional results.

Parties will now enter negotiations for the formation of a majority government. With such a commanding performance, CNRT is favoured to be the lead party in a new coalition government, suggesting one likely aspect of continuity with the 2007 result. Its partners this time, however, will only be clear once the inter-party negotiations are complete. While a new CNRT-led alliance with the Democratic Party and Mudança is regarded by many as more likely, party negotiations could yet throw up surprises. The likely division of seats allows for three potential combinations to make up a majority. None can be ruled out until the outcome of the negotiations is announced.

Frente-Mudança is almost certain to support CNRT, but this combination alone will likely fall one seat short of a majority. If indeed Fretilin does receive twenty-five seats, an alternative parliamentary majority of thirty-three seats with the Democratic Party is also available. This places the third party in a far stronger bargaining position with CNRT than if Fretilin receives twenty-four seats. Pending the final allocation of seats, the Democratic Party finds itself with considerable leverage in the kingmaker role, despite having underperformed slightly relative to 2007. The third possible combination is a “grand coalition” of CNRT and Fretilin. Though seen as an outside chance, it has been the subject of extensive popular rumours, and would also represent a symbolic unification of the east and west of the country. It would be unwise to rule any outcome out at this early stage, though this one would clearly require major and difficult compromise.

Whatever the final outcomes, the good news for Timor-Leste is that the existence of alternative majorities will do much to keep any new government accountable across the life of the parliament, whatever its complexion.

CNRT itself will be delighted with Saturday’s result, which saw it emerge ahead in nine of Timor-Leste’s thirteen districts, achieving a 12.5 per cent increase on its 2007 performance. For Fretilin, the small gain of 1 per cent will be a disappointing return on five years of campaigning, though it does at least appear that attempts to further splinter the party’s base are now meeting resistance. The party will find considerable consolation in having the pressure point of an alternative majority, and also in having led the count in one of the western districts beyond their eastern heartland, Manufahi. The party has been using its radio station to urge calm among its supporters. Whatever the outcome of negotiations, it is likely this result could lead to renewal in the party’s current leadership positions.

For the Democratic Party, the results give it a strong hand in negotiations for ministries despite a reduction in its 2007 vote, and it will likely be satisfied with that outcome. On the other hand, the potential availability of an alternative CNRT-Fretilin “grand coalition” sets some limits on its ability to make excessive demands with this new found power.

For the country, the focus must now be on peace and stability as the United Nations and the International Stabilisation Force prepare to withdraw later this year. Many also argue that it is time to review the government’s approach to the spending of Timor-Leste’s main resource, the $10 billion petroleum fund. The outgoing government’s large-scale expenditure on infrastructure to kick-start development – totalling some $3 billion over its term – has created a small wealthy class in Dili and produced impressive economic growth rates on paper, but it has also seen a growth in corruption, rising economic inequality and inflation, and increasing disparities between urban and rural development outcomes.

As one of Timor-Leste’s leading NGOs, La’o Hamutuk, argues, unless spending is made more sustainable, the incoming government may be the last to have access to the substantial capital wealth from the oil fields, with most revenue expected to flow over the next ten years. With these warnings in mind, regional development must be a priority for the incoming government, as Timor-Leste potentially heads towards the “perfect storm” of a massive demographic explosion in young adults entering the labour market, just as known oil revenues cease to flow in the mid 2020s. Without the ability to provide young people with adequate opportunities in the districts, social and economic problems within Dili will be magnified enormously. By the next election in 2017 it may be too late to contain these problems. •