Access Denied: A Bibliography of Suppressed Australian Literature

By Geoffrey Cains | Longueville Media | $49.95 | 310 pages

A few days after joining the University of Queensland Press as publishing manager in late 1983 I found myself threatened with criminal libel over a book UQP had released several weeks before. This was no idle threat: it came from Queensland’s chief justice, Sir Walter Campbell, who also happened to be chancellor of the university of which UQP was a department. The book in question was the meticulously researched second volume of Ross Fitzgerald’s landmark history of Queensland, From 1915 to the 1980s.

As soon as it hit the shops, copies were snapped up by the political and legal fraternity, and it wasn’t long before one of Campbell’s lawyer friends drew his attention to page 354. This summarised a long-running defamation case against Joh Bjelke-Petersen by 1976 Australian of the Year John Sinclair. For more than a decade Sinclair’s Fraser Island Defence Organisation had been a thorn in the side of the Bjelke-Petersen regime, which had expanded already extensive sand-mining leases on the island despite export bans imposed by both the Whitlam and Fraser governments.

In early 1977 the premier had questioned whether Sinclair could perform his work as a state government employee while leading the conservation campaign against sand mining. Within days of issuing his writ against Bjelke-Petersen over these comments, Sinclair learned that his job had been abolished and he’d have to move away from the Fraser coast. Four years later the Queensland Supreme Court finally awarded him $500 in defamation damages plus legal costs — a decision Bjelke-Petersen appealed.

Before this appeal could be heard, the position of chief justice became vacant. It was at this point in his narrative that author Ross Fitzgerald wrote a sentence he never realised would expose him and his publishers to the threat of criminal libel and even imprisonment:

On 21 May 1982, the Queensland Full Court, led by Queensland’s new chief justice, Sir Walter Campbell, who had been appointed to the position despite the opposition of the Queensland Bar Association and the Liberal attorney-general Sam Doumany, in a unanimous decision overturned the Supreme Court ruling and awarded costs against Mr Sinclair who was left with a $50,000 debt.

Even though Campbell had not been Bjelke-Petersen’s first choice for chief justice, Sir Walter read page 354 of Fitzgerald’s book as a serious libel on his judicial independence. UQP was ordered by the university to pulp all warehouse stock along with copies still on sale in bookshops and any review or complimentary copies that had gone out. It was a military-style operation that took our sales and marketing staff the best part of a week to carry out.

They were so successful that very few copies of the original edition escaped. I still have mine, which I showed to Geoffrey Cains when he was compiling Access Denied: A Bibliography of Suppressed Australian Literature. As he points out in his entry on volume two of Fitzgerald’s history of Queensland, when UQP reissued the book in 1984, Sir Walter Campbell had been surgically removed. I remember sitting alongside Ross at UQP’s beautiful silky-oak boardroom table one afternoon as we carefully defused that dangerous paragraph.

Access Denied has been a labour of love for Cains, a renowned book collector and bibliophile as well as a dermatologist and lecturer in medicine at the University of Wollongong. He established the annual National Biography Award in 1996 and his substantial collection of Australian literary manuscripts and correspondence is now held by the State Library of Victoria.

Based on his PhD thesis, Access Denied tells the fascinating stories of almost 200 editions that were withdrawn — before, during or after publication — by their authors or publishers, often because of the threat of legal action, as happened to me at UQP forty years ago.

Arranged alphabetically by author, the descriptive bibliography covers more than two centuries of Australian cultural history — from the 1770s to 2015 — and focuses on suppression rather than government censorship. Cains hopes that other scholars and bibliophiles, including booksellers, will add the stories of other suppressed books as they come to light.

For me, two of the most interesting authors in Access Denied are Indigenous. David Unaipon (1872–1967) was an inventor as well as an author and preacher who believed in the equivalence of traditional Aboriginal and Christian spirituality. In the mid 1920s he sold the copyright in his manuscript of Aboriginal myths to Sydney publisher Angus & Robertson who transferred the copyright to physician and anthropologist William Ramsay Smith.

British publisher Harrap asked Smith to put together a volume of Aboriginal myths, which appeared in 1930 as Myths & Legends of the Australian Aboriginals. Although this was Unaipon’s work, it was published under Smith’s name: strictly speaking, a case of the author rather than the book being suppressed. Fifty years later, scholars Adam Shoemaker and Stephen Muecke discovered this flagrant breach of copyright and edited a new edition for Melbourne University Press in 2001 under the title Legendary Tales of the Australian Aborigines, with Unaipon finally acknowledged as author.

A generation later than David Unaipon was poet, playwright, artist and Black activist Kevin Gilbert, whose first book was a collection of his poems written during fourteen years in prison. Illustrated by the author, End of Dreamtime was almost immediately withdrawn from sale in 1971 after Gilbert accused his publisher of bowdlerising and tampering with the text. The following year he helped organise the Aboriginal Tent Embassy but was forbidden to travel to Canberra because he was under strict parole conditions. A dozen years later he established and chaired the Treaty ’88 Committee in the years leading up to the bicentenary.

Other writers have suppressed their first books for more personal reasons. Nobel Laureate Patrick White’s first effort, Thirteen Poems, was published privately by his mother in about 1929. It was not so much suppressed by the author as invisible to literary scholars for many years, having been listed in the Mitchell Library catalogue under “P.V.M. White” rather than “Patrick White.”

Ruth White also arranged and paid for the printing of her son’s next book, The Ploughman and Other Poems (1935), in an edition of just 300 copies, few of which sold. It has become part of literary legend that White, later in life, tried to buy up and destroy any copies of The Ploughman that came on the market. He also refused to allow his first novel, Happy Valley, published by Harrap in London in 1939, to be republished. According to Cains, “White feared a libel suit from the family of one of the characters in the novel.” It was finally reissued by Text Publishing in 2012 — a decade after his death.

Other novels suppressed, and later reissued, include the pseudonymous Helen Demidenko’s Miles Franklin Award–winning The Hand That Signed the Paper (1994), Kylie Tennant’s Ride on Stranger (Angus & Robertson, 1943), and Come in Spinner (1951) by Dymphna Cusack and Florence James.

My own favourite suppressed novel is screenwriter Tony Morphett’s Fitzgerald (Jacaranda Press, Brisbane, 1965). Cains quotes from a newspaper article he found tipped into a proof copy of Fitzgerald when researching his bibliography:

Let us not forget the case of Tony Morphett whose novel about an artist was withdrawn when an artist of the same surname, who was unknown to Morphett, threatened a defamation action. The novel, rewritten, was published as Thorskald (1969), and Morphett had to suffer countless japing telegrams from friends, claiming that they were solicitors representing an artist named Thorskald.

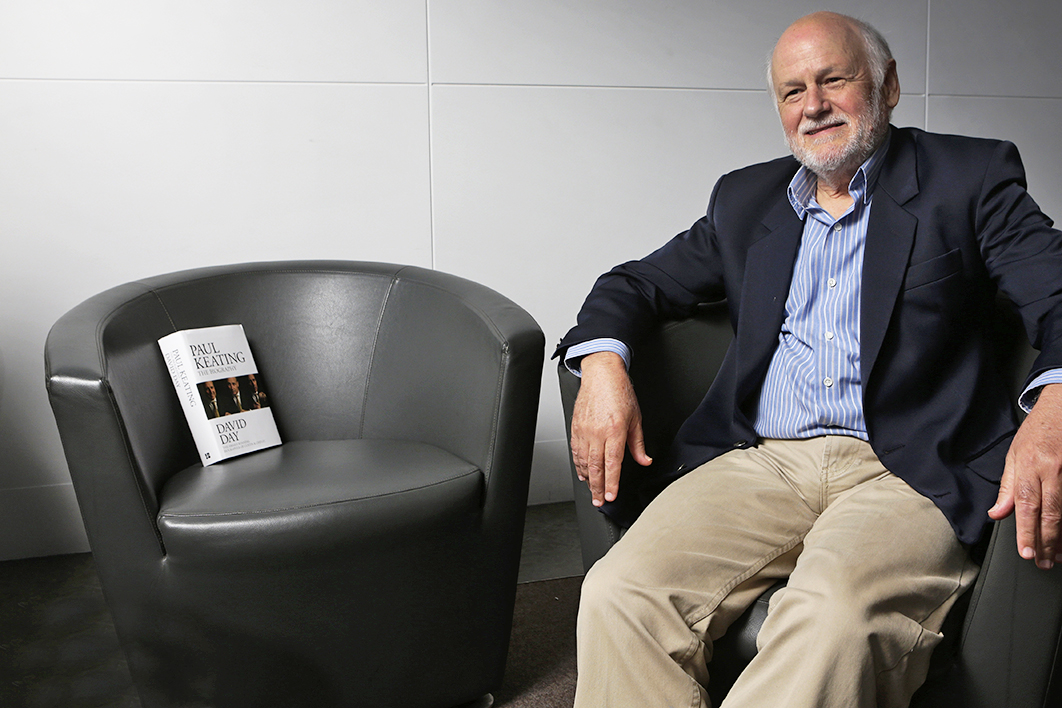

The most recently suppressed book in Access Denied is David Day’s 2015 biography of Paul Keating, published by HarperCollins in a print run of 8000 hardbacks but withdrawn from sale and pulped after a legal threat from the former prime minister. HarperCollins also agreed to meet Keating’s legal costs.

In the notorious case of Bob Ellis’s Goodbye Jerusalem: Night Thoughts of a Labor Outsider (1997), Liberal politicians Tony Abbott and Peter Costello brought a successful action for defamation on behalf of their wives against the publisher Random House. Cains helpfully tells his readers that the offending text was to be found on pages 472–73. The original edition was pulped, those pages amended, and the book reissued in a new edition three months later.

Printed full colour and beautifully produced by Longueville Media, Access Denied is a large-format hardback with dozens of illustrations, including book covers, photographs and rare manuscript items. It’s currently available from online retailer Booktopia for only $38.50. •