If song lyrics were treated as poetry, Taylor Swift would be the most popular poet in history. She even invokes the romantic image of the poète maudit — the cursed poet; the poet who is mad, bad and dangerous to know — in the title song of her latest album, The Tortured Poets Department.

Swift’s songs are said to be confessional, but as a literary academic of advanced years I exist so far outside her fan base as to be blissfully ignorant of her biography. The lyrics in this case appear to allude to a relationship with a self-destructive partner, but I read them as an ironic fable of the troubled relationship between poetry and song itself. Swift is aware that it’s easy to fall for the louche but charismatic boy poet, yet she knows that his masculine image is passé — like writing your poems on a typewriter — and that he no longer has the cultural authority he once possessed: a cultural authority that she has in spades.

Even so, for all their personal differences, because she still enjoys his “show” and can “decode” him (her words), it’s apparent they retain a creative connection. Towards the end of the song he moves a ring from her middle to her ring finger in a gesture of commitment. Although — as a universally acclaimed, fabulously wealthy, multi-award-winning singer-songwriter — Swift may not be quite so tortured, she implies that she belongs in the same department.

Another literary academic, Sir Jonathan Bate, a Shakespeare scholar no less, has admitted to being a Swiftie, praising the singer’s linguistic flair and literary allusions. “This isn’t just high-class showbiz,” he wrote in Britain’s Sunday Times, “Taylor Swift is a real poet.” But my new book, The Wild Reciter, is not about Taylor Swift and, although the ways in which poetry and song lyrics relate are a significant theme within it, its range is wider and more eclectic.

I begin with Swift because, like Bob Dylan before her, while her obvious skills as a wordsmith invite comparisons with high culture, her phenomenal success as a popular singer simultaneously casts doubt over the value of her words. That’s why Bate’s claim that she’s “a real poet” seems less like a statement of acknowledged fact and more a provocation. Like the image of the tortured poet, poetry still carries page-based, typewritten, elite connotations — even though this privileged meaning has long been underwritten by more popular forms of verse that often, in the past especially, involved performance (including singing).

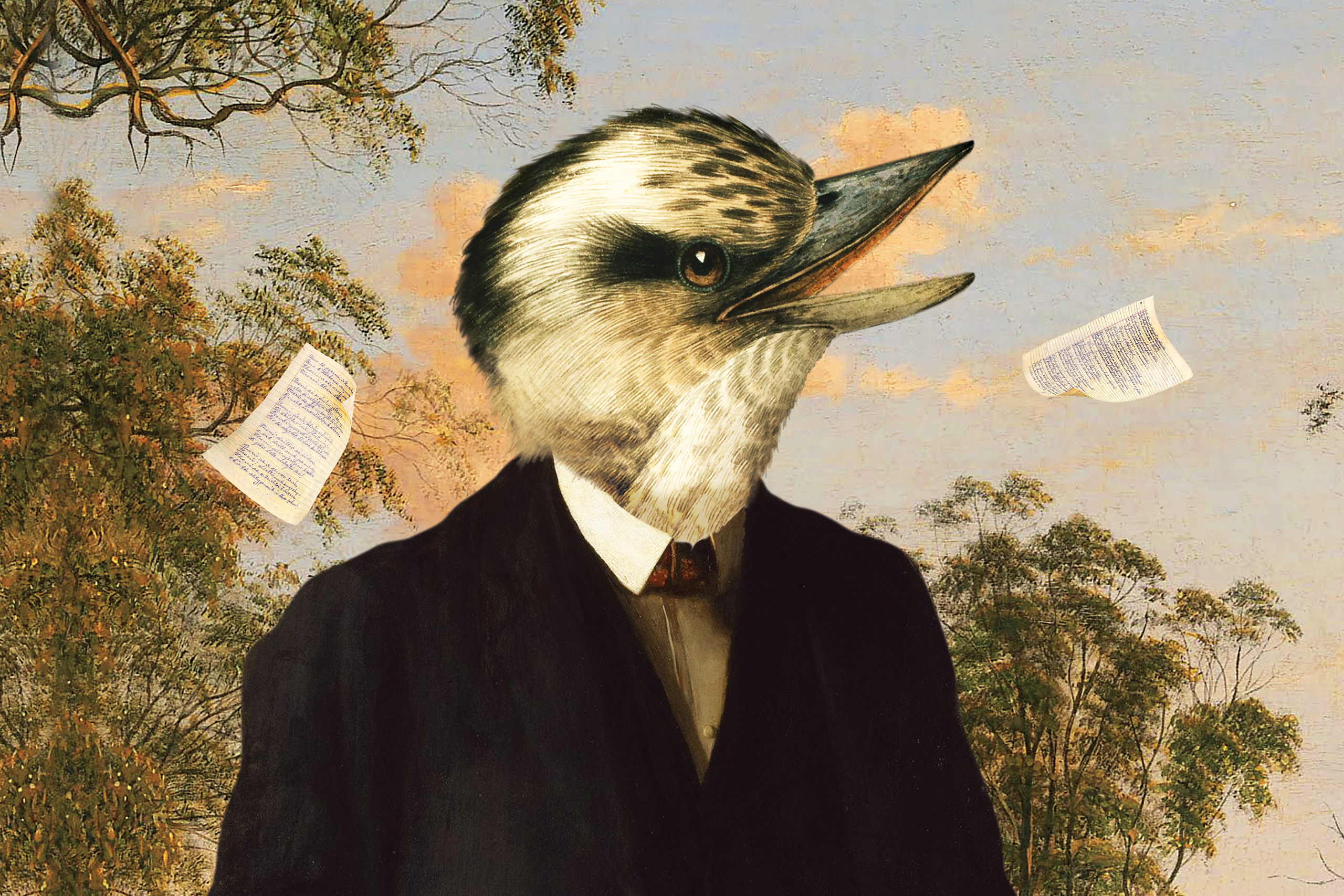

Against the tortured poet I invoke the amateur reciter, sometimes called an “elocutionist,” who is an equally old-fashioned and eccentric figure, and today almost wholly forgotten. Unlike the typical poète maudit, reciters could be female as well as male, and when delivering their favourite verses in front of an audience could become so unrestrainedly histrionic as to attract the epithet “wild” from one local wit in the 1920s — hence my title, “the wild reciter.”

Now an extinct species, the wild reciter was once so common as to be a pest. For my purposes, he or she is not so much the hero of this book as a symbol of a time long gone when poetry had mass appeal, and was everywhere read, memorised and performed. In other words, a motif for something presumed lost: poetry as a social activity; poetry as a form of entertainment.

Light-years behind Taylor Swift in terms of high- class showbiz professionalism, the wild reciter represents poetry’s neglected and — in the best possible sense of the word — vulgar past, offering a perspective that might also speak to its present and future as a demotic art.

In Australia today most people have hardly any use for poetry in the elite sense at all. If we encounter it in school, it’s apt to be ransacked for its paraphrasable content, or made otherwise assessable in the mandated fun of a creative project, rather than read and enjoyed, privately or in performance, in and of itself as a special arrangement of language and sound. Some of us encounter it at university in comparable ways, to much the same effect perhaps. To approach poetry from a literary-critical perspective can sometimes feel like entering a conspiracy theory that invites you to take the red pill by insisting, “You may think this poem means X, but you’ll soon find that it really means Y.”

Yet, for all that academic study dominates its reception, poetry is undoubtedly still read and still performed in this country without becoming either a hermeneutic exercise or piece of work to be graded, and I dare say that it remains a significant medium through which the young, especially, are given to express their experiences, emotions and identities. Witness the appeal and success of poetry slams, and of Instapoetry. The trouble is that, like casual risk-taking, most people soon grow out of it.

Instead, or in any case, everybody currently hears what amounts to poetry in the words of popular songs, which, facilitated by the gramophone and radio, began to replace page verse as the most common form of lyrical utterance during the early twentieth century. The rhymes of hip-hop imply a still stronger kinship. If few people can now quote from well-loved poems, a great number will recall lines or whole verses of favourite song lyrics — often in the phrasing and intonation of the original singer. (Hence the phenomenon of the mondegreen, or misheard lyric. How many think Jimmy Barnes in “Khe Sanh” sings “The last train” — instead of plane — “out of Sydney’s almost gone”?) For many in the music industry, however, trying to isolate the lyrics of a song from its performance is on a par with murdering in order to dissect.

Similarly, poetry written expressly to be performed is different, more diminished, less vitalised, when read on a page rather than heard as part of a spoken word or slam event. The historic link between song and poetry reminds us that all language was once embodied, that embodiment — through volume and tone of voice, bodily movement, gesture and facial expression — is fundamental in oral communication, that words that are spoken or sung generate different possibilities of meaning than those which live only on the mute page, and that poetry remains an oral, as well as a literate, art form. Candy Royalle (1981–2018) was a headlining performer of her poetry on the Sydney scene, but her posthumous collection A Trillion Tiny Awakenings (2018) can offer only a shadow of her luminous live presence.

I am interested in the ways in which poetry has been created, communicated and consumed within everyday life in this country from around 1890 until the present day: from bush ballads to slam. Of course, “everyday life” is not a static category any more than “poetry” is, and both continue to change with the advent of transformational new technologies. Although the internet now massively facilitates the publishing and performance of poetry, it’s a melancholy truth that, for all this healthy diversity, poetry is no longer regularly consumed across all ages and classes. In that sense, it’s no longer indisputably one of the arts of everyday life, as the genres of popular music are.

That this has occurred shows the ways in which new communication technologies — sound recording, cinema, radio, television, the internet — have transformed audiences as much as they have transformed the ways in which poetry is made. By tracing the changing modes of creation, communication and consumption of poetry over the past 135 years, and by taking account of those new technologies and the audiences generated by them, I’ve aimed to arrive at a larger, more capacious notion of what poetry is.

The Wild Reciter ends with a famous quotation from a well- known British-American poet backhandedly celebrating his art, so by way of sounding a cautionary note I’d like to bookend it here at the start with another well-known example that queries the cultural value of poetry — or, more precisely, what we mean when we say poetry. For, to be brutally frank, it’s very easy to be put off by the stuff. As the American modernist Marianne Moore declared, “I too, dislike it: there are things that are important beyond all this fiddle.” And fiddling is what much high literary poetry can seem like: aridly introverted, wantonly obscure or leadenly “playful,” and at times a combination of all three. I myself have long enjoyed an antipathy to any form of “visual” or concrete poetry. In contrast, my partner is very fond of photographing poetic graffiti around inner Sydney. Here’s just one example, stencilled in cursive script in a back lane in St Peters:

This wall has a soul beneath her mission brown skin,

Formed of colour and spray, stencil and sprawl.

She howls of political protest and whispers of loves lost,

A cultural pin-up with stories etched deep in her flesh.

My academic soul might chafe at the sentimental clichés, but this is perfectly effective in its place, and even moving. And its handwritten look and its location are intrinsic to its meaning. By making direct reference to the surface upon which it appears it may be classed as playful, but it’s neither introverted or obscure, and it reads exactly like what a great many people who don’t like “poetry” would, for want of a better word, call poetry. If I have a problem with this, I’m part of a tiny elitist minority, and I need to get over myself if I want to understand the interrelationship that necessarily exists between “poetry” as a specialised genre of interest to a few and poetry as a familiar art form accessible to everybody, as close as graffiti or the lyrics of a Taylor Swift song.

Another sample of poetry written on property, below a rear window overlooking a lane in North Newtown, maybe helps to explain why:

ALICE

RULES

(I WAS NAK’D

WHEN I WROTE THIS)

Somehow this manages to be both sweet and creepy in about equal measure. Yet whatever the author was or wasn’t wearing when they wrote it, the fact is that nobody is ever really naked when they write, because we’re clothed in language as social beings from the moment we begin to speak. The history of poetry is immemorial, but I want to show that — just as a can of spray-paint is able to shape written language in wholly new ways — through wholly new media technologies, poetry also possesses a modern popular history very different from its past.

But can this last example of graffiti be classed as poetry — with or without inverted commas? For its author there were evidently things more important beyond such a fiddling question. As Marianne Moore ultimately conceded about her art, “Reading it, however, with a perfect contempt for it, one discovers in/ it, after all, a place for the genuine.” Again I start to chafe, and want to ask, What is genuine? But then, if it’s a quality to be uniquely attached to poetry, I guess the answer will depend on what you understand by that word too. •

This is an edited extract from The Wild Reciter, published earlier this month by Melbourne University Press.