In the current environment, Labor’s win in Queensland is unusual. It is the first time a Labor state or federal government has been re-elected unequivocally anywhere in Australia since Anna Bligh’s historic breakthrough in March 2009. Are the times shifting Labor’s way? Or is this, as Malcolm Turnbull tells us, a result peculiar to Queensland?

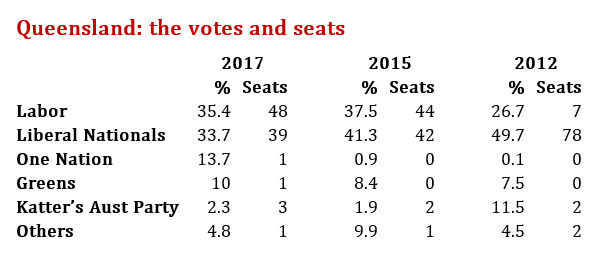

It may seem overblown to say that Labor’s win was unequivocal. It attracted only 35.4 per cent of the vote, not normally a winning number. In a proportional representation system like New Zealand’s, it would have won only thirty-five seats in an expanded ninety-five-member parliament. (One Nation would have won thirteen and the Greens ten, instead of getting one each.) But in a system of single-member electorates, with the voters having plenty of choices, 35.4 per cent of the vote gave Labor forty-eight seats, a three-seat majority in a parliament of ninety-three seats.

In the end, only Townsville was really close, with Labor holding on by 214 votes. At last year’s federal election, late counting of postal, pre-poll and absentee votes swung Queensland seats like Flynn and Capricornia to the Liberal National Party. That didn’t happen this time; the LNP vote rose overall, but Labor pulled clear in the seats that mattered.

Is this telling us that Labor has regained the momentum across Australia? This year it has won a sweeping victory in Western Australia, won re-election in Queensland, and even attracted a swing, relative to last year’s federal vote, of 5.3 per cent in the recent Northcote by-election in inner Melbourne.

From late 2010 to early 2014, Labor hardly won an election outside the Australian Capital Territory. Since the Turnbull government scraped home last July, Labor has won every election: taking government in Western Australia and the Northern Territory, and holding it in Queensland and the ACT. Are voters taking out their frustration with the Turnbull government on its state partners?

In a sense, Annastacia Palaszczuk’s was a normal victory. Since the fall of the Bjelke-Petersen government, the state has reverted to its old pattern of voting Labor at state elections and Coalition at federal ones. Between 1990 and 2020, the Coalition will have spent just five years in government in Brisbane, and twenty-five in opposition, the worst record of any major party anywhere in Australia. Even the ACT Liberals have spent more time in government.

This loss reflects an extraordinary shift since Campbell Newman’s record landslide win in 2012. Newman’s arrogant, elite-driven style of government saw him lose thirty-six seats, and power, after just one term. The LNP has now lost further ground, with its vote shrinking from 41.3 per cent in 2015 to 33.7 per cent now. One Nation is only part of its problem.

In another sense, the result is extraordinary. Take out the ACT, where Labor and the Greens have won five elections in a row and are now rusted-on as the government. Take out South Australia, where Labor has lost the last two elections on the votes, but won them on the seats. Since the 2007 election, Labor lost power everywhere else — Western Australia (2008), Victoria (2010), New South Wales (2011), Queensland (2012), the Northern Territory (2012), Federal (2013) and Tasmania (2014) — yet it went on to win back power in Victoria, Queensland and the Northern Territory after a single term, and on the latest EMRS poll this week in Hobart’s Mercury, the Tasmanian Liberal government looks like being the next one-termer, with just 34 per cent of the vote now, down from 51 per cent at the 2014 election.

On that poll’s findings, the government Tasmanians elect early next year will be a minority government. Labor too has just 34 per cent of the vote (up 7 per cent from 2014), the Greens 17 per cent, Jacqui Lambie’s party 8 per cent and others 7 per cent. Are Labor and the Greens ready to form a harmonious coalition government in Tasmania — or is that politically impossible?

South Australia, too, goes to the polls early next year. While the bookies have the Liberals as favourites, that too will almost certainly be a minority government — assuming that, in the three-party contest, both sides preference Nick Xenophon’s SA-BEST rather than each other. If Xenophon sticks to his pledge to form no coalitions and sit on the crossbenches, it will be a novel and possibly unstable experiment, whichever side “wins.”

The Andrews government in Victoria will face the voters in November, and the infrequent polls are coming up with very different results. The latest, by Essential Research, gives Labor a 52–48 lead, whereas polling by Galaxy and ReachTel in the first half of the year for the rabidly anti-Labor Herald Sun reported the Coalition with landslide leads, 53–47 and 54–46 respectively. I suspect the odds are more like 50–50.

The next NSW election is not until March 2019. Two recent polls, by ReachTel for Fairfax and Essential for the Guardian, suggest that Gladys Berejiklian has won back some ground after Mike Baird’s premiership imploded. They report the Coalition’s two-party lead as 52–48 and 51–49 respectively, suggesting that Labor is certainly in the contest.

Then there’s the Turnbull government. Believe it or not, it’s still less than halfway through its term. Yet even the punters (who tend to overstate Coalition chances) have Labor as odds-on to unseat it when the next election is held. Except in the ACT, and perhaps Western Australia, it’s an unstable political environment for governments all over Australia.

Queensland’s election was unusual in another way: it delivered a majority government. But only just, and only because the system of electing MPs in single-member electorates favours the major parties over contenders from the fringes.

The Greens exploited Labor’s ambivalence over the Adani coal mine to win 10 per cent of the vote, their best result in a Queensland state election. Yet they won just 1 per cent of the seats — the new inner-suburban seat of Maiwar, taken from the Liberals — and were competitive in only two other seats. It’s interesting to note that all three seats, although adjoining, are in separate federal electorates.

Katter’s Australian Party picked up the coastal seat of Hinchinbrook, giving it the complete set of the three state seats that roughly make up Bob Katter’s federal seat of Kennedy. But it won nothing else, and theirs was not the brand that rebellious voters were looking for outside Katter country.

That brand was One Nation. Its 13.7 per cent vote is misleading; it stood in only two-thirds of the seats, and Pauline Hanson is correct in saying that her party averaged 20 per cent of the votes where it stood. (Of course, the seats it bypassed were mainly in inner/middle Brisbane and the Gold Coast, where it has little support. Hanson herself won just 2 per cent of the Senate vote last year in inner Brisbane.)

But even in its best areas, One Nation’s primary vote was too low for it to top the poll anywhere. To win seats, it needed preferences. Its best vote was 34.4 per cent in Lockyer, the seat Pauline Hanson almost won in 2015. But to overtake the LNP, it needed Labor preferences — and while most Labor voters in 2015 ignored the ticket and preferenced Hanson, not this time. Throughout the state, Labor put One Nation last on its how-to-vote cards.

That meant any gains One Nation made had to be in Labor seats, on LNP preferences. They proved to be unreliable. In Mirani, where central and north Queensland merge, LNP preferences pushed One Nation’s Steve Andrew ahead of Labor to win the seat. But in Logan, its next best prospect, Hanson’s candidate was former Hell’s Angels bikie Steve Bannon — so the Liberals preferenced Labor.

In Thuringowa, the LNP directed preferences to One Nation’s candidate, sex shop owner Mark Thornton, but many Liberal voters deserted the ticket, and preferenced Labor. In Maryborough and Keppel, the preference flows from the Coalition must have been tighter — no details have yet been released — but not tight enough. Labor won both seats by 2.5 and 3.1 per cent respectively. One Nation finished second in twenty seats, but these were its two closest misses. And in this game, silver medals don’t matter.

The decision to direct LNP preferences to One Nation in most seats where it mattered ended up giving only one seat to Hanson’s party. What about the quid pro quo? Did One Nation preferences help the LNP?

No, screams the Australian, once again blaming One Nation for any losses by its favourite party in Queensland. It claims that One Nation preferences “handed” three seats to Labor — Aspley, Mansfield and Redlands — yet provides no evidence. Nor could it: no preference counts have been released. At last year’s federal election, most One Nation voters ignored the party ticket (indeed, probably never saw it) and did what they liked. Whatever the how-to-vote ticket said, they split their preferences roughly 50–50.

Seat by seat, the LNP’s share of those preferences last year varied from 58 per cent in Maranoa to 43.5 per cent in Longman. Longman was the only seat where One Nation’s how-to-vote card decided the outcome, pushing Labor above former junior minister Wyatt Roy. (Preferences from One Nation voters gave Labor a paper-thin victory in Herbert — but that choice was made by the voters, not the party, which issued a split ticket.)

At this election, excluding the One Nation vote, the Coalition was trailing Labor in all of Aspley, Mansfield and Redlands. To win any of them, it probably needed 60 to 70 per cent of One Nation preferences. Last year, One Nation couldn’t deliver that even in a safe outback seat like Maranoa, even when it directed preferences to the Coalition. Yes, it’s a bigger party now, and its preferences may be more disciplined, but where’s the evidence?

It wasn’t there in the inland north Queensland seat of Burdekin, where One Nation directed preferences to Labor. Yet its voters’ preferences clearly flowed to the LNP’s sitting member, Dale Last, pushing him above Labor to take the seat. The Oz didn’t even notice that.

In almost two-thirds of the seats it contested, One Nation in fact directed preferences to the LNP ahead of Labor. The only seat in which its preference directions clearly changed the result was Pumicestone, between Brisbane and the Sunshine Coast, where they gave the seat to the LNP. It’s possible that that also happened in Bundaberg. The Oz didn’t report any of those facts.

Nor did it report the obvious explanation for the LNP’s defeat: since 2015, it has lost six of its eleven seats in Brisbane, two from the redistribution, and four at the election. It now holds just five seats in and around the Queensland capital; Labor and the Greens hold thirty-six. No party can hope to run Queensland with such a puny base in Brisbane.

Mark the contrast. In Brisbane and the Gold Coast, the LNP lost four seats, and gained none. North of Brisbane, the party lost two seats — Hinchinbrook to the Katter party, Noosa to a local independent, Sandy Bolton — but picked up three: Bundaberg, Burdekin and Nicklin.

It didn’t lose the election in regional Queensland. It lost the election in Brisbane — and many believe its decision to give preferences to One Nation was one reason for that. It is in Brisbane that it needs to lift its vote. A decision by the Turnbull government to help fund the Cross River Rail project would be a good start.

The federal Coalition needs to scrape off the barnacles, and start again. There is no left-wing or right-wing infrastructure. Voters turn off when the PM and his ministers argue that any major projects proposed by Labor state governments are bad, and deserve no federal funds, while any proposed by Coalition state governments are good, and deserve billions. I’m sure most voters would welcome ministers being capable of speaking for a minute without attacking Labor. The PM himself should lead the way. •