A hundred years ago Australia was preoccupied with the news from the wartime battlefront and still coming to grips with the appalling loss of life. Press coverage focused on the role of Australian forces in what by then seemed an interminable conflict. Buried deep inside the newspapers of the day, though, was another unfolding drama in a faraway country, a drama both puzzling and inexplicable: the months-long Russian revolution.

Early reports of the unrest in Russia, a key ally, focused on its implications for the war. But as 1917 wore on, and events moved at an ever-accelerating pace, avid newspaper readers found themselves in the uncertain predicament of Bob Dylan’s Mr Jones: something is happening here but you don’t know what it is, do you?

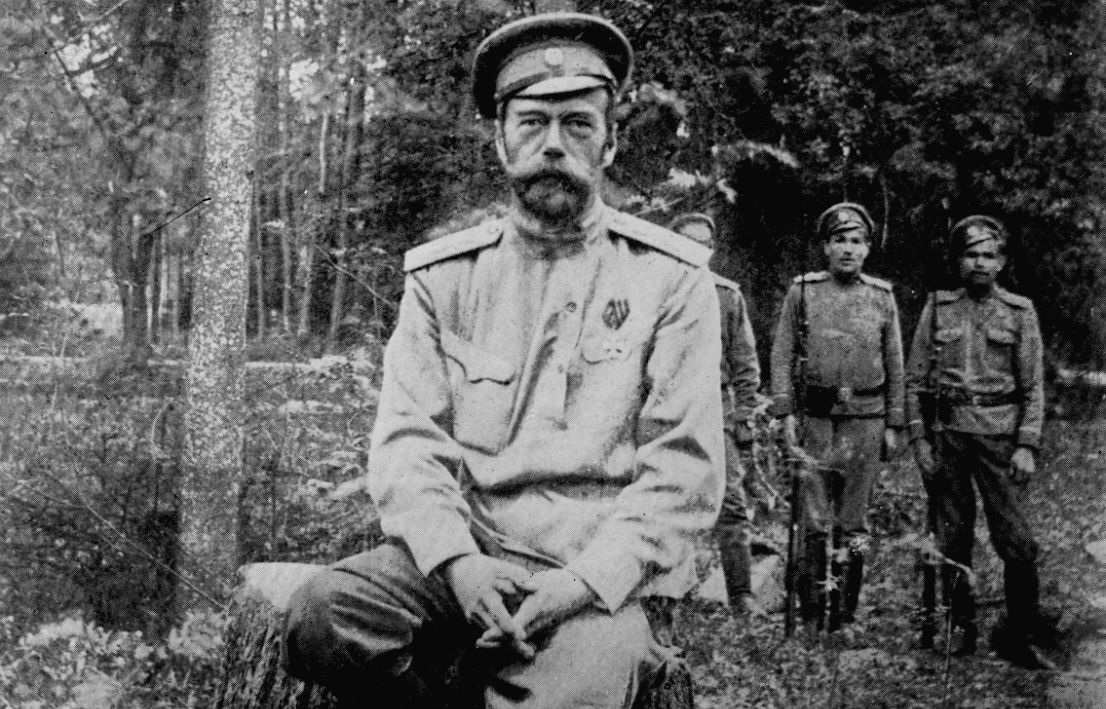

On 2 June 1917, the Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate told its readers that the unfolding revolution was “the most tremendous event the war has yet produced.” The paper advanced several possible causes, some of which lay deep in the past while others, such as food shortages, were very much in the present. But at the heart of it was the ineffectual leadership of Tsar Nicholas II, “a simple and honest, though weakly obstinate mystic,” who was said to be dominated by his melancholic wife. (The tsar had abdicated earlier in 1917; he and his family would be murdered by the Bolsheviks in 1918.) The revolution had popular support, said the paper, noting that “this upheaval would have been impossible were not all Russia solid for reform.”

On 9 June, the Catholic Advocate in Melbourne reported on “the general approval expressed by the press of Great Britain of the Russian Revolution” and the hope that a weak autocrat might be replaced by a stable democratic government. It was “certainly satisfactory to find that the Czar has been swept aside by the rising tide of democracy,” but what would happen next, the paper said, was difficult to predict.

The Advocate quoted a Russian émigré commentator’s remarks about a new movement, Slavism, which was the antithesis of the displaced autocracy. Slavism aimed to restore autonomy to all the smaller nations of Europe and, such being the case, “must be opposed to the Pan-German idea of world domination.” But the paper was sceptical:

We would be glad to share this optimistic view of the situation; but when the people who are to carry out this programme are considered, it will be found that there is room for misgiving. Even the optimistic view naturally taken of the position and intentions of the people of a great ally in the war cannot hide the fact that, taken as a whole, Russia contains the most ignorant of all the peoples of Europe.

The danger now, the paper said, was “that an irresponsible mob may get control.”

As for its impact on the war effort, there was still talk of a Russian advance westwards. “It appears that the most that can be expected, before the next winter settles down on Europe,” the Advocate reported, “is that the Russian armies will guard the eastern frontier, leaving the work of forcing the Germans back to the Allies on the other fronts.”

On 30 June, quoting a Sydney man whose brother was on the spot, the Singleton Argus carried a page-one story about German pamphlets being dropped behind Russian lines. The pamphlets warned Russians that they were being deceived, and that the English were to blame for deposing the tsar:

The English have deceived your Czar, and led him into the war in order to conquer the whole world with his help. At first the English went with your Czar — now they have risen against him because he did not agree with their cunning demands. The English have dethroned your Czar, who was given to you by God himself. Why has this happened?

The story was deepening. On 3 July, many Australian newspapers carried a despatch from the Times in London, quoting an English journalist who had reached Russia and, after talking to many people, was convinced that the revolution “was not only against the Czar but against the war.” Those leading the revolution held that capitalism was the root of all wars, and that no distinction existed between the sword-rattling German Kaiser and the pacifist American president, Woodrow Wilson. The correspondent warned that at the end of the conflict “delegates from ravaged States will have to discuss peace with idealists and fanatics, who are determined to put the whole world right.”

That month, as local skirmishes flared all over Russia with the final collapse of the old order, the short-lived provisional government of Alexander Kerensky took office. On 14 July, the Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate carried a graphic account of a British nurse in Petrograd (as St Petersburg had been renamed after the war broke out) at the time of the February revolution. The nurse, attached to the Red Cross, had travelled from Romania and, having been warned that revolution would break out any day, found herself “right in the heart of the uprising of a whole nation claiming its liberty.”

She described how a maid at the hospital she was visiting called her excitedly to the window to watch a procession:

The soldier patriots in their grey coats, on foot and in motor-lorries and motor-cars, were going down the street in a steady, orderly manner, protecting a crowd of starving men, women, and children, who were walking in the centre of the procession. At their head was a band playing the “Marseillaise” and a large red flag borne aloft…

[Then] there was a sudden outburst of fierce firing from above, and soldiers and women and children fell to the ground, and the street soon became a shambles. The firing was from machine-guns controlled by the police, who were in ambush on the roof of this hotel and who tried to bring about a wholesale slaughter of the people below. It was astonishing how self-possessed the crowd was in the face of this murderous attack. I saw the soldiers who had not fallen immediately enter the hotel and make their way to the roof, where they shot the cowardly police, captured the machine guns, and brought them down to the street and fixed them on the back seats of the motor cars and the lorries.

On 23 July, the Bendigo Independent in Victoria tried to tell its readers a little about this far-off place increasingly in the news, explaining that “the country that is known as Russia occupies rather more than half of Asia.” Seventy times the size of Britain, the country’s population was only four times greater. “Russia, in general, is a country of magnificent distances, sparsely inhabited by nations who widely differ from each other in their origin, language, modes of living, religion, education and intelligence.” The Russian upper and middle classes, the paper graciously conceded, “are almost on an intellectual level with the rest of Europe,” but “the Russian peasantry are far down in the list of civilised nations… Force and superstition were factors that held Russia together as an empire.”

Of the dethroned tsar and his family, who were now interned in the Winter Palace near Petrograd, the Independent opined that:

the dismal political history of Russia for hundreds of years past is repeating itself in the reports by cable that he is endeavouring to destroy himself, and has to be continually watched by attendants… But revolutions within revolutions are evidently pending, and the political future of the great, disorganised country of so many mixed nations and degrees of civilisation is dark indeed.

On 11 August, the Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate cautiously welcomed developments, but worried that “the Russian workers, who have just been emancipated from the rule of one of the absolute autocracies in the world, have not yet learnt to use their freedom. They are like prisoners who, after years in dungeons, are suddenly brought out into the sunshine and cannot bear the light.”

The paper urged statesmen and trade union leaders to go to Russia to help. “It is not too late for this proposal to be carried out,” it said, “and we are certain that it would be welcomed by none more heartily than by Russians who love freedom and their country, and who need all the help and guidance that the older democracies can give them.”

A fortnight later, the Sydney Morning Herald carried a review of Russia in Revolution, engineer Stinton Jones’s first-hand account of events in Petrograd. His enthusiasm over certain aspects of the revolution, wrote the reviewer, is “tempered with forebodings.” “In the earlier part of the book,” the review continues:

he is hopeful; later he begins to wonder whether the powers of law and order have the situation in hand; at the end there is a hint that the reformers, with a legitimate programme, may have invited the co-operation of forces that they cannot control; may have unsealed the bottle whence issues a baleful genie with an increasing sphere of malevolence.

In Melbourne, the Age reported on 17 September that a privately screened film about events in Russia, despite having apparently been heavily censored, allowed the “state of unrest” to be gauged “by the immense crowds in the streets.”

It was an accurate observation. The tottering remains of the provisional government were swept away by the Bolsheviks less than two months later. On 12 November, many Australian newspapers carried a widely distributed wire service account that read:

Yesterday’s revolution differed from the last. There was complete apathy amongst the population, who did not know another revolution had commenced until evening. The Ministers have taken refuge in the Winter Palace, where, with a small corps, they are pledged to fight to the last. In the evening the extremists had gained the approaches to the Palace.

Not surprisingly, the Brisbane Worker sided with the revolutionaries against Kerensky’s short-lived government. “From the chaotic accounts of the new revolution in Russia one fact now has become apparent,” reported on 22 November:

It is that the dictatorship of Kerensky is entirely overthrown, and that when calm has been restored government, both civil and military, will be in the hands not of the agents of compromise, but of the representatives of the masses. There has been bloodshed both in Petrograd and Moscow, but a neutral who has lately returned from Russia repudiates the stories of cruelty and atrocity. This man, M. Edstroen, president of the Swedish Electric Company, stated that he saw nothing of the bloody fighting chronicled in foreign newspapers. The military schools certainly were damaged, but he had heard nothing of the reported cruelties to the women’s battalion. On the contrary, the Bolsheviks, who are now in command, maintained excellent order.

By year’s end, commentators were trying to make sense of the tumultuous events. On 29 December, the Echuca and Moama Advertiser and Farmers’ Gazette worried that the world had turned “topsy-turvy” with all the “strange events brought about by the greatest war the world has ever witnessed.”

The anonymous writer feared that the Russian boast that the revolution had been brought about with less bloodshed than that of the French revolution of 1789 was not likely to be realised. “It is possible and probable that when full knowledge is gained of what has happened in Russia,” a tragic story outrivalling that of France might be revealed. “The mass of Russian people indeed seems to have been but little, if any, further advanced in enlightenment than those of France in those far-off days when Paris was a shambles and the whole land stricken to the core with fear and doubts.”

Presciently, the Daily Observer in Tamworth also detected the beginnings of the emergence of the United States as a world power. The year 1917 “has been more eventful than any other of which there is a record,” said the paper. “If only for the remarkable collapse of the great Russian Empire it would have stood by itself. But the Russian revolution is only one event, and not by any means the greatest. The intervention of America in the world struggle” — its entry into the conflict in Europe in 1917 — “will probably be reckoned by historians as the happening of greatest consequence in this war.” ●