The Russian analyst could not have been more explicit: “The lessons of the intervention in Syria are clear,” he wrote on 8 December in the business daily Kommersant, “First of all, it demonstrates the enormous limitations of Russia’s ‘great power’ politics and the politics of interventions abroad”:

Moscow does not have enough military strength, resources, influence and authority for effective military intervention outside the former Soviet space… After [the full scale invasion of Ukraine in] 2022 this became even more apparent. It is completely possible to bluff about your power and abilities on the international stage, but one should not start to believe in one’s own bluff.

He’s right. Russia’s claim to be a great power, maybe even a superpower, is based on historical memory rather than current objective reality. As I argued in my 2023 book, Russia is a regional power, not a global one. Its economy is slightly bigger than Canada’s and Italy’s, about half the size of Japan’s, one-twelfth America’s and an eighth of China’s. Tiny Australia has an economy 75 per cent of mighty Russia’s. The population Putin rules over is significantly smaller than Bangladesh’s, Brazil’s or Nigeria’s, to say nothing of China or the United States. India has ten times as many people.

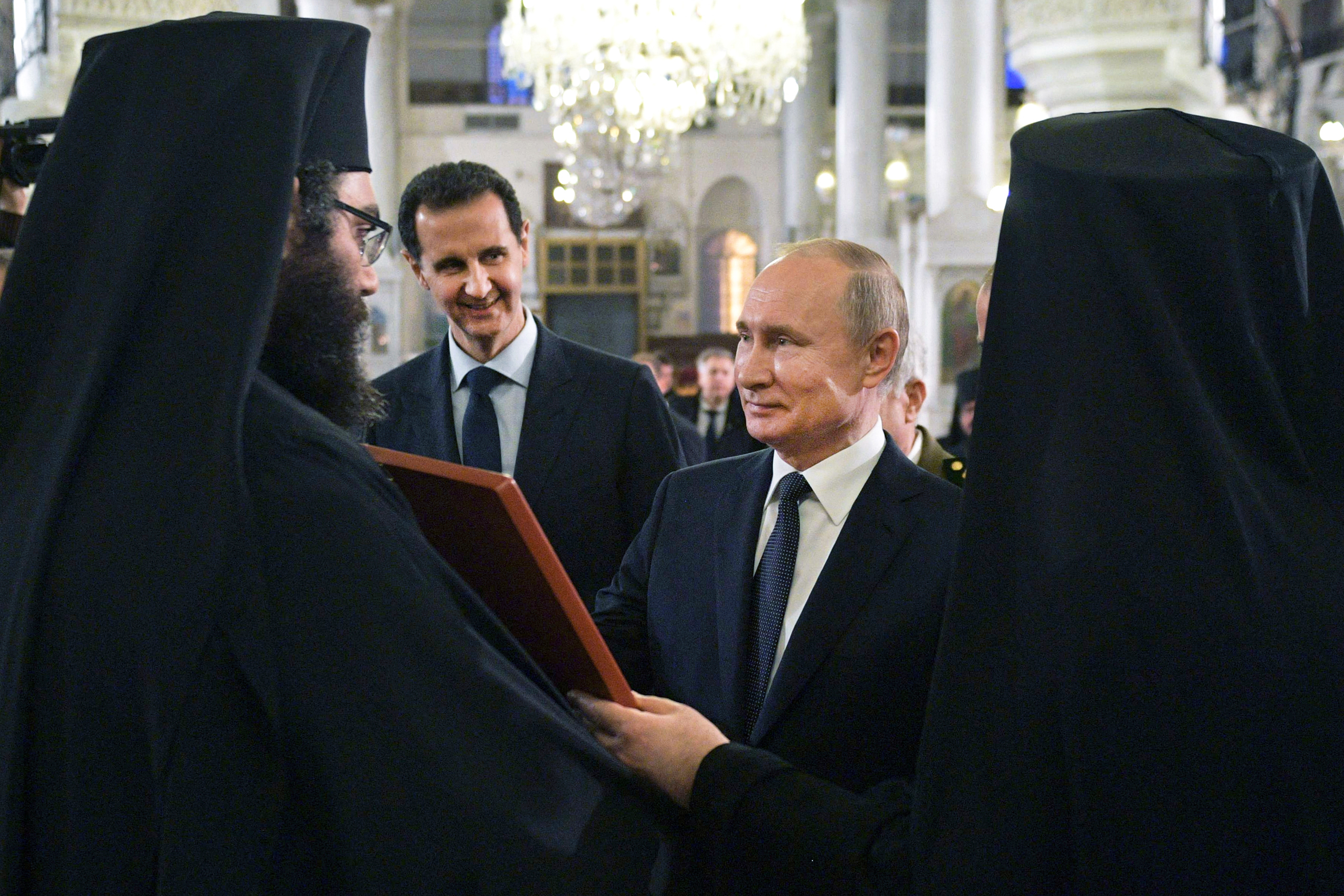

Given its relatively meagre resources, Russia has punched significantly above its weight over the past decade. President Vladimir Putin is an excellent tactician who is willing to leverage the nuclear threat he possesses. He has repeatedly confounded Western leaders who had grown used to the idea that the era of wars of conquest was over.

The economic base of Putin’s power play is oil, which Russia produces at a rate only exceeded by Saudi Arabia and the United States. It has allowed him to build a military significantly larger than that of the US. In terms of number of soldiers, Russia comes sixth in the world, with nearly as many people under arms as China (but less than half the number of troops North Korea keeps at the ready).

This claim to great-power status came at a price, however. Today, Russia is over-extended and its position is potentially perilous.

As the opposition forces marched on Aleppo and then on Damascus, the Russian airforce targeted them with several sorties, as usual hitting civilian targets including a hospital and a refugee camp. But Russia no longer had the assets and the time to bomb them into submission, as they did in 2015–16 when its aviation and ground troops played a major role in securing Assad’s survival. The war in Ukraine took precedent and the destruction of mercenary leader Yevgeny Pigozhin left fewer boots on the ground in Syria.

After Assad’s fall, with Russian commentators wringing their hands, the government tried to limit its losses by establishing working relations with those it had only days earlier condemned as “terrorists.” At stake are a naval base and an airport, both essential to Russia’s projection of power in the region and beyond.

Syria is one site of Russia’s multi-pronged assault on perceived US hegemony over the globe. If the attack on Ukraine was meant to rebuild the Russian empire, the intervention in Syria was to establish a bridgehead for power projection into the Middle East and Africa. It was a central step in the attempt to challenge the status quo and build a multipolar world order fit for mid-sized dictatorships like Putin’s.

The assault on the status quo gained momentum a decade ago. In 2013–14, Russia lost political control over Ukraine, where a popular revolution ousted the pro-Kremlin government. Putin reacted by annexing Crimea and fostering a war in the east of Ukraine, sometimes fought by proxies, sometimes by Russian troops themselves. In September 2015, Putin transformed his longstanding support for Assad into a military intervention, which gave him an airbase as well as a forty-nine-year lease on the naval base in Tartus, established during Soviet times in 1971. It is Russia’s only port in the Mediterranean.

With Syria stabilised and Russia’s role secure, Putin faced more unrest at his doorstep in 2020–21, when the brotherly dictatorship in Belarus was rocked by large-scale protests. These were clubbed out of existence by a well-entrenched regime supported by Russia. At home, Putin had protests repressed in early 2021, sparked by the return and arrest of opposition leader Alexey Navalny, who had survived an earlier assassination attempt by the regime. Some analysts see the 2021 clashes with the opposition as part of the motivation for attacking Ukraine a year later: a successful little war to distract from troubles at home.

That, of course, did not go as planned. Nearly three years later Russia is bogged down in a war of attrition so terrible that Putin had to accept Iranian and North Korean support. The two fellow dictatorships provided drones, shells and, in the case of North Korea, soldiers. Russia is advancing, but slowly. As of late October 2024 it occupied just over 18 per cent of Ukraine’s territory, down from 27 per cent at its greatest extent in 2022. Ukraine still clings on to Russian territory in Kursk region, which it seized in a surprise attack in August.

Since the start of the war, Russia has lost enormous numbers of men, maybe 198,000 of them dead and 550,000 wounded. Ukrainian forces have destroyed more than 9000 tanks, twenty-eight warships and boats, nearly 700 fixed and rotary wing aircraft, 2500 cruise missiles and more than 18,000 drones.

At present, Putin’s best hope is that Donald Trump will pull the rug out from under Ukraine by refusing to further support its war effort. This remains to be seen — and whether that would mean the end of the war is yet another matter.

As of late 2024, then, Putin’s position is more precarious than often appreciated. He has lost Syria, and whether he can keep his military bases there is an open question. These are important to his wider strategy: as the Guardian’s Pjotr Saur wrote this week, the two Syrian bases “hold an outsized importance to Russia: the Tartus facility gives… access to a warm water port, while Moscow has used the Khmeimim airbase as a staging post to fly its military contractors in and out of Africa.” That continent, in turn, is a major site of Russia’s projection of power, where “mercenaries, disinformation, election interference, support for coups, and arms for resources deals” combine to secure support.

African backing, in turn, is crucial for the wider goodwill Russia tries to foster in the global south. Losing the Syrian bases would have “major implications for Russia’s ability to project power in the Mediterranean Sea, threaten NATO’s southern flank and operate in Africa,” assesses the Institute for the Study of War.

Closer to home, in the southern Caucasus region, Putin’s success in securing a pro-Russian government in Georgia might also be under threat, although at this stage it is difficult to predict whether Georgia will go the way of democratic and anti-Russian Ukraine or of dictatorial and pro-Russian Belarus. Further east, the dictatorships in Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan) have meanwhile pivoted to a “multi-vector foreign policy,” designed to carve out a space for their own agency in international affairs. While not breaking fully with Russia, they certainly are no colonial dependencies of the former metropole any longer.

Things might still turn out well for Putin. But as Syria suggests, dictatorial military ventures can be like personal finances: they collapse “gradually and then suddenly.” The Russian analyst cited above is certainly concerned that Russia’s failure to secure Syria might point to things to come in Ukraine: “if not today, then tomorrow or the day after tomorrow.” •