Covid anti-vax conspirators offer a thriving line in coffee and cookies on the east coast of Australia, running alternative cafes from Cairns to Nimbin and down the spine of the Great Dividing Range to Katoomba and points further south. Local customers complain about big government, big capital and (intriguingly) the New York–based Council on Foreign Relations.

A sign in the window of one anti-vaxxer hangout, across from Katoomba’s railway station, reads “We stand united against government tyranny!!” Bill Gates smiles threateningly from a silk-screen print, vaccination needle in hand, alongside an advertisement for Chakra group-healing sessions. In this part of town, conspiracy theories and alternative healing are served with coffee and cake on what appears to be a sustainable anti-vax business model.

Falun Gong pamphlets can be picked up nearby. Adherents of Falun Dafa (as they call their faith) promote healing through religious chants and breathing exercises and work to expose the brutality the Chinese government inflicts on believers back in China. They certainly are persistent, and they were in the news again recently when Communist Party general secretary Jiang Zemin died in Shanghai.

Thirty years earlier, Jiang had taken fright when a peaceful phalanx of Falun Dafa practitioners queued outside his official residence in the old imperial palace district of Beijing petitioning for recognition of their faith as a religious community. Infuriated by their presumption, he branded them a superstitious cult and banished them outright. Thousands perished in the persecution that followed and others languished in prison awaiting forced organ transplants, if adherents’ claims are to be believed.

There’s no viable business model for superstitious belief in China, where science and rational planning carry the day and the apparently irrational desires of common people count for little.

But here’s the thing. China is opening up again after three years of intermittent but severe Covid lockdowns. Over that period it managed to keep the virus in check but failed to prepare the country’s people for a timely transition from epidemic lockdowns to a more flexible model of pandemic management. Why this neglect, if China’s government is as rational, capable and forward thinking as it claims to be ? Why lift lockdowns heading into winter rather in the warmer months earlier this year when the virus was less active? As a result of this series of policy failures, China could be heading for a health crisis on a scale the world has not seen since the crisis that shook India in 2020.

Some analysts say the party erred in abandoning its long-held commitment to science by succumbing to an anti-vax syndrome of its own devising. The historian Adam Tooze recently argued that China’s government undermined public confidence in readily-available Sinovac and Sinopharm vaccines by allowing vaccine conspiracy theories to flourish online. It’s true that the government tolerated efforts to counter criticism from abroad that Chinese vaccines were inferior to Western ones (they are reported to work reasonably well after three doses) but the effect of that campaign was more likely to have enhanced confidence in Chinese vaccines than undermine it.

If anything, China’s problem is that its system of government is obsessed with science and rational planning to the point that it fails to take account of what people want. Doubt is essential to science. The science scepticism of Falun Dafa practitioners and anti-vaxxers may be over the top, but the lack of scepticism in China is no less troubling.

Democracy wears a lab coat

Big Whites, as they are called, are the neighbourhood cadres, volunteers, medics and enforcers who carry out the central government’s Covid lockdown policies clad in bulky white hazmat coveralls. The term refers to the robot in the Disney film Big Hero 6 programmed to perform medical procedures using instruments built into its bulky white-clad body. It’s a neat comparison. China’s Big Whites administer Covid tests, police entry and exit to residential compounds, and patrol streets, distribute food and detain anyone who gets in their way — by force if necessary.

The way Big Whites methodically patrol neighbourhoods in their white hazmat uniforms captures something missing from the Disney film. This is the role of science as a strong arm of politics and public policy in China and in the everyday directives of China’s Communist Party. The party does not just believe in science, it embodies and enforces it.

As a party, the communists trace their ideological foundations to scientific socialism, which they place on the same plane as the science that underpins maths, physics and chemistry. More than that, Marxism is considered foundational to all other sciences: “The intellectual foundation of science is the scientific theory of Marxism,” Xi Jinping told national educators in December 2016. The party’s ideological commitment to science lends science a place in the governance of China matched only by its place in Stalin’s Soviet Union. This is an early-twentieth-century pre-quantum kind of science in which everything is certain and quantifiable and open to precise and predictable explanation. The connection of science with Marxism can be read to mean that whatever keeps a Marxist–Leninist party in power has to be good science.

This science of political certainty can be traced to the founding of the Communist Party in the early 1920s, when “Mr Science and Mr Democracy” (as they were called at the time) first entered the country. They came smartly dressed, faddishly foreign and unabashedly modern, and seemed destined to set the country aright. Mr Science didn’t arrive lumbered with the doubt and questioning that comes with scientific method but brought instead a modern kind of certainty to displace the older certainties of the Confucian canon. Any democracy modelled on such a science had to be certain too.

One outcome was that the new leaders of modern China expected more of democracy than it could possibly deliver. Winston Churchill’s complacent remark about the imperfections of democracy — “It has been said that democracy is the worst form of government except all those other forms that have been tried from time to time” — is widely read among China’s communists not as a concession to the uncertainties of the human condition but as a shameful acknowledgement of liberal democracy’s failure to achieve perfection.

As the editor of one of China’s leading journals of international relations remarked of Churchill’s comment, “for a statesman of the capitalist class, it must have been really difficult to express this opinion.” That was a revealing comment: only a party committed to scientific socialism would imagine it could achieve perfection or deny it had a problem dealing with the uncertainties of everyday social and political life.

The Communist Party and its state bureaucracy are structured hierarchically to achieve a certain kind of perfection in relaying messages and commands and assigning responsibility up and down a many-layered command structure grounded in scientific socialism. Atop the structure, the central leadership embodies scientific rationality and sits beyond criticism or reproach. Beneath the leadership sit the cadres.

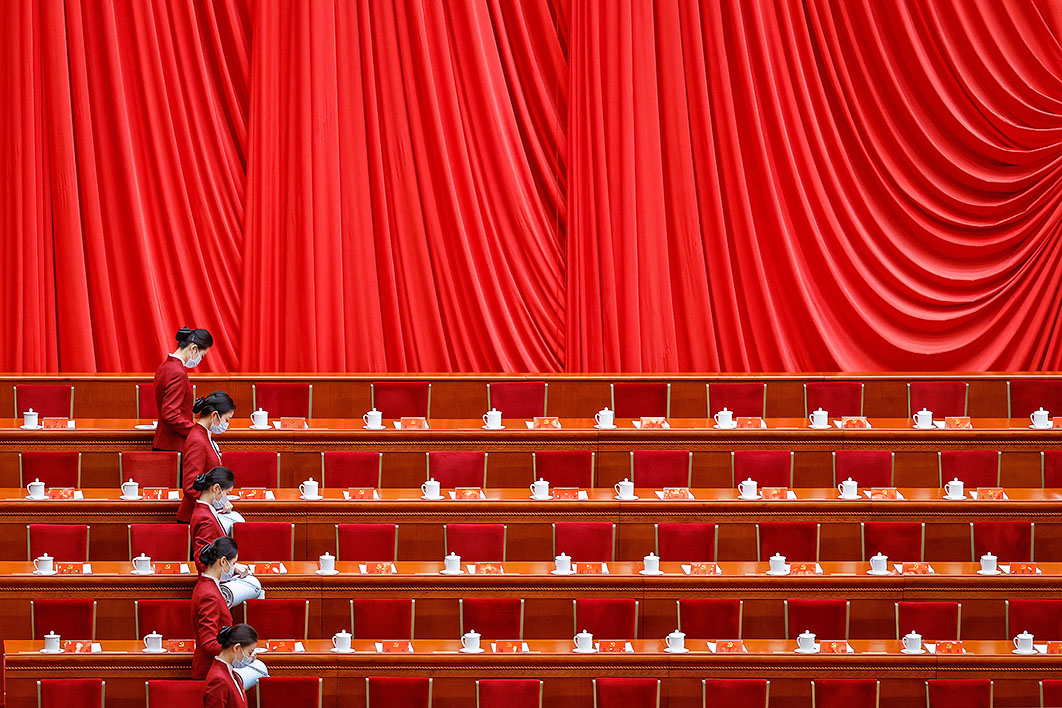

In this system, the rituals surrounding appointment of a supreme leader such as Xi Jinping are performed with such precision that nothing can be allowed to spoil them. The capital all but grinds to a halt ahead of a five-yearly national party congress as industry is silenced, streets closed off and other meetings and events cancelled. This is not the time to announce a national policy shift that could spell uncertainty. So the summer leading into the party’s twentieth national congress in October, when Xi was appointed supreme leader for as long as he liked, was no time for modifying his “dynamic zero” Covid policy.

On this model of scientific government, there’s room for cautious policy experimentation at the margins — on local finance for example — but where experiments succeed all credit is attributed to the farsightedness of the leadership, and where they fail, local cadres are left wondering what happened and picking up the pieces.

With few regulatory or legal instruments to guide them, those cadres often end up making arbitrary decisions about who was at fault, who should be put away, whose property should be confiscated and what should be done next. When things go terribly awry, they themselves are targeted for punishment. Overall, the structure makes little provision for heeding the wishes of common people or holding cadres accountable to the communities they govern.

Science and people

Churchill’s defence of democracy was a comment on human nature as much as it was on democracy: he prefaced it with a comment on the difficulty of governing “in this world of sin and woe.” Scientific socialism has no patience for such a world. Much has been written about elite attempts to remake China’s people or, in party terms, to elevate the “quality” (suzhi) of commoners to match the expectations the leadership places in them. In the meantime, the party makes up for the shortcomings of ordinary people by creating a quasi-nation out of its own cadres, as I argue in my recent book Cadre Country, to be perfected in place of the people as instruments of party rule.

Here’s where things get interesting in Covid-afflicted China. If the party’s tens of millions of cadres are to carry out their leaders’ instructions in every corner of the land — north, south, east, west and centre as Xi Jinping is fond of telling them — then China’s cadres need to be as finely attuned to the commands of the leadership as a lab technician to the instructions of a lead scientist.

The words “science” and “precision” pepper XI Jinping’s speeches on his cadre force. Still they constantly disappoint him. When things don’t work out as the leadership plans, and communities take their anger and frustration onto the streets, it’s not the fault of the leaders who drafted scientific policies and issued clear instructions. It’s the fault of the cadres for failing to follow instructions with the precision science demands.

That’s the way communist cadre systems work. Russian historian Moshe Lewin traced the habit of communist leaders turning on and blaming the cadres beneath them to Stalin’s 1925 lecture to trainee cadres at the Sverdlov Party Institute. “The only problem is cadres,” Stalin told the trainees. “If things are not progressing, or if they go wrong, the cause is not to be sought in any objective conditions: it is the fault of the cadres.” It is this Stalinist science of government that has landed China in the mess it finds itself.

Science and Covid policy

Stalin’s management science has been playing out in China’s recent pandemic policy dilemma. On 10 November, not long after the close of the twentieth national party congress, Xi Jinping presided over a meeting of his new Politburo Standing Committee to receive a report on “Twenty Measures” for the prevention and control of the most recent Corona virus epidemic. The following day, the State Council issued a statement on the Twenty Measures, explaining that they called for “scientific and precise” prevention and control at the local level. The new formula calling for “scientific and precise” prevention and control was not a relaxation, the statement continued, but an unswerving affirmation of Xi Jinping’s standing policy of dynamic-zero control.

Alongside the State Council’s statement, official newsagency Xinhua reported that China’s experience managing Covid had shown the leaders’ polices to be “completely correct” and that all measures taken were “scientific and effective.” The new policy encouraged local officials to calibrate risks according to the needs of their neighbourhoods, and to adjust their behaviour by abandoning “unscientific practices” such as over-prescribing Covid tests. Cadres should strive to “overcome formalism and bureaucratism and put an end to incrementalism and ‘one-size-fits-all’ approaches,” they were told. Even so, this was not a time for relaxation of prevention and control.

What was a provincial leading cadre to make of this central directive? Online is a record of the Heilongjiang Provincial party group receiving the central directive and disseminating it to cities, districts, counties, and townships across the province. On 18 November, provincial governor Hu Changsheng convened the province’s Leading Small Group on Covid Work and urged his subordinates to “resolutely implement the spirit of the important instructions of General Secretary Xi Jinping’s scientific, precise and uncompromising implementation of epidemic prevention and control measures.”

Hu instructed the provincial government to “conscientiously implement the Twenty Measures of the State Council… and adhere to scientific and precise prevention and control.” Local party and government officials were told to adhere unswervingly to the national “dynamic zero” Covid policy and, in case anyone had missed it, to avoid formalism and bureaucratism.

Judging from the published record of the meeting, Heilongjiang provincial officials had no idea what central authorities expected of them under the new Covid management regime, other than to repeat its vague formulas and implement them as bureaucratically as possible.

Some local governments thought they knew better. The city government of Shijiazhuang, in Hebei Province, tried to escape formalism and bureaucratism by lifting restrictions on local residential compounds, only to find itself in trouble when local citizens objected to its “scientific, precise and uncompromising” measures for implementing the new policy. The city’s party secretary and mayor were reportedly dismissed and lower level officials were left baffled.

At the neighbourhood level, mixed signals from on high were paired with disincentives for local officials trying to implement the new policy with something like scientific precision. “We were told to relax the overly strict Covid prevention rules [but] could still get fired for not stamping out cases on time,” the Financial Times reported a county-level cadre as saying.

If local cadres were hoping to find sympathy or support from on high, they were disappointed. It was all their fault. On 1 December, Xinhua issued a detailed explanatory note on what central authorities had intended with the announcements coming out of the Politburo Standing Committee meeting of 11 November. “The correct meaning of scientifically precise prevention and control,” according to Xinhua, could be summed up in the phrase “quickly seal and unseal — and unseal wherever possible” (快封快解 应解尽解). For good measure, it added that any confusion over the centre’s directive was the fault of local cadres, not the fault of the policy or the leadership, since implementation of the “quickly seal and unseal” policy was the “responsibility of cadres.” It all came down to the quality of cadres and cadre management in Xinhua’s authoritative account.

Around the same time, the recently appointed head of the party’s Central Organisation Bureau, Chen Xi, published a major statement in People’s Daily extolling Xi Jinping’s visionary leadership and calling for the recruitment of a higher calibre of local cadres — “loyal, clean, and responsible” — than those Xi found himself commanding at present. Again, the solution lay in science: what the country now needed was a “scientific path [科学路径] for cadre management.” Heading into winter, the situation was set up for failure, with cadres trying to implement a central policy for which no one was prepared to take responsibility (certainly not Xi Jinping), while party leadership doubled down on its search for a more scientific path for cadre management.

To achieve the precision his policies require, Xi Jinping has to replace the cadre force he actually commands with a body of more faithful and responsive cadres. For the past three years he has been railing against the forty million cadres under his direction, complaining that they are prone to “kneeling before their leaders to flatter and fawn” while mistreating their subordinates; sitting on their hands rather doing anything useful; and complaining that their workload is too onerous and higher management too demanding.

By 2019 Xi had endured enough of their complaints. He called for a thorough cleansing of cadre ranks and their replacement by a team of “loyal, clean and responsible cadres” who could be relied upon to follow his directions unswervingly.

China has an enduring problem if its supreme leaders go on pretending that they are all wise and that their system of government can attain perfection. A little more doubt and lot more democracy would probably go some way to fixing it. •