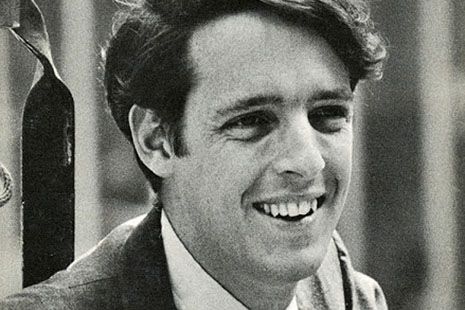

IN HIS MID-TWENTIES, the American writer Joe McGinniss created a landmark work that opened our eyes to how politics is marketed to voters. He was also the subject of one of the most surgically precise strikes in journalistic history when his ethics were compared – unfavourably – to those of a convicted murderer. In significant ways McGinniss’s work, and how it was received, illustrates just how far long-form journalism has come in the past four decades or so.

When McGinniss managed to inveigle himself into the team advising Richard Nixon in his quest for the presidency in 1968, Americans were accustomed to relatively perfunctory and superficial media coverage of such events. The shining exceptions were Theodore White’s book-length accounts of the 1960 and 1964 campaigns, both of which were simply entitled The Making of the President. White set out to take readers with him into the smoky backrooms where the human drama of the campaign was on show. For a book about politics to succeed, White wrote, it “must have a unity, a dramatic unfolding from a single central theme so that the reader comes away from the book as if he [sic] had participated himself in the development of a wonder.”

Phooey to that, said McGinniss, whose book The Selling of the President 1968, showed that the smoky backrooms had actually been devoted to developing a very effective advertising campaign to transform Nixon from a dour grump fearful of television to someone who could appeal to ordinary voters. Central to that transformation was Roger Ailes, now head of the Fox News Network. “Let’s face it, a lot of people think Nixon is dull,” says Ailes in McGinniss’s book. “They look at him as the kind of kid who always carried a book bag. Who was forty-two-years-old the day he was born.”

The importance of image-making and selling short, simple messages may be so commonplace today as to be a truism, but The Selling of the President 1968 played a pioneering role in shaping that perception. It became one of the top ten bestselling non-fiction books for the year, catapulting the youthful McGinniss to national fame.

Largely undiscussed at the time, except in those smoky backrooms, was the question of just how McGinniss gained such extraordinary access to the Nixon campaign and what exactly were the ground rules for that access. What was on the record, and what was off? Was there any distinction between the two in such circumstances? If anything and everything was fair game for the journalist, it did not take much imagination to see that in future only fools and narcissists would ever let any of them within cooee.

It was on these issues that Janet Malcolm, a longtime writer for the New Yorker, shone a light of laser-like intensity after McGinniss wrote about a horrific case in which an army doctor, Jeffrey MacDonald, was accused of murdering his pregnant wife and two small children.

The opening paragraph of Malcolm’s 1989 article, published in book form the following year, has since been called “one of the most provocative in American journalism” by Elizabeth Fakazis. It’s worth quoting in full:

Every journalist who is not too stupid or too full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he [sic] does is morally indefensible. He is a kind of confidence man, preying on people’s vanity, ignorance, or loneliness, gaining their trust and betraying them without remorse. Like the credulous widow who wakes up one day to find the charming young man and all her savings gone, so the consenting subject of a piece of non-fiction writing learns – when the article or book appears – his hard lesson. Journalists justify their treachery in various ways according to their temperaments. The more pompous talk about freedom of speech and “the public’s right to know”; the least talented talk about Art; the seemliest murmur about earning a living.

Malcolm’s words created a furore among journalists. They asked: what about less-than-credulous widows, or downright sneaky politicians who tried to manipulate journalists to write them up in flattering terms or to bury anything that made them look bad? How could Malcolm condemn an entire profession on a single case, asked others? Why did she not mention a libel suit in which her own journalistic practice was being questioned? And, finally, why did she write with such infuriating certitude?

Martin Gottlieb, writing in Columbia Journalism Review, said the vehemence of many journalists’ responses suggests Malcolm had hit a nerve. Fakazis noted that there had been little media interest in the libel suit that Jeffrey Masson had brought over her hostile profile of him in the magazine until after Malcolm’s article about McGinniss had been published in the New Yorker and then it had been overwhelmingly negative.

The journalists’ objections were not entirely misdirected, however. Malcolm doesn’t ignore the role of sources, but she does underplay the source’s role and power in their relationship with journalists. And she pins a great deal on this one case study of journalistic practice.

Malcolm did ignore in her article the lawsuit brought against her over an earlier article, and probably should not have. And the elegantly stinging certitude that characterises Malcolm’s prose points to a paradox in her work; she articulates, even delights in, the ambiguities of issues in prose of ringing unambiguity.

The dual effect of Malcolm’s approach has been to substantially create and influence a debate, both for better and for worse. Her insights were soon reflected in the academic literature, and are routinely cited, usually with a wry grimace, by working journalists today. The problem is that Malcolm’s writing offers an insight into journalist–source relationships rather than a framework for analysing the range of characteristics in such relationships in their complexity.

Her insight, I think, also applies less to daily journalism where practitioners rarely spend enough time with a source to develop an emotional relationship that might later feel like betrayal to the source. They are more relevant to those working on long-form or book-length projects, as Joe McGinniss was for his 1983 work about the MacDonald case, Fatal Vision.

MacDonald and his legal team approached McGinniss to write about his murder trial, offering unfettered access to MacDonald and the legal team’s strategy in exchange for more than a quarter of the US$300,000 advance and one third of any royalties from the book that McGinniss would write about the case.

When the book was published, MacDonald sued, not for defamation but for breach of contract. How did this happen? Well, McGinniss agreed to the insider access he would get to the MacDonald team, and to the handsome book advance, but during the trial he began doubting the innocence of his principal source. He didn’t share these doubts with MacDonald or his legal team, but by the end he agreed with the jury that MacDonald had murdered his family.

He had developed a close relationship with McDonald before the trial, staying at his home with him, drinking beer, watching sport on television, jogging together and, as Malcolm puts it, “classifying women according to looks.” But to write a book-length account he needed information about MacDonald’s childhood, his marriage and military career. Because he wasn’t allowed to interview MacDonald in prison, he gathered that material primarily by correspondence. The prisoner wanted to see the manuscript but McGinniss refused on the ground that he needed to retain editorial independence. It was only when Fatal Vision was published that MacDonald learnt unequivocally of McGinniss’s change of mind.

In his action against McGinniss, MacDonald cited a clause in their agreement exempting the journalist from libel claims “providing that the essential integrity of my life story is maintained.” The breach of contract case was heard in 1987 before a judge and jury. Intriguingly, according to Malcolm’s account, “five of the six jurors were persuaded that a man who was serving three consecutive life sentences for the murder of his wife and two small children was deserving of more sympathy than the writer who had deceived him.”

Malcolm quotes extensively from a series of around forty of McGinniss’s letters to MacDonald in jail and from his cross-examination at the trial. They showed in great detail the rarely exposed underbelly of journalistic practice. In his first letter, McGinniss sympathises that anyone could see MacDonald had not received a fair trial, and laments:

Goddamn, Jeff, one of the worst things about all this is how suddenly and totally all your friends – self included – have been deprived of the pleasure of your company. What the fuck were those people thinking of? How could twelve people not only agree to believe such a horrendous proposition, but agree, with a man’s life at stake, that they believed it beyond a reasonable doubt? In six-and-a-half hours?

If McGinniss often presented himself to MacDonald as a friend, he later told Malcolm that the former army doctor was clearly trying to manipulate him, and that he had been aware of this from the outset. “But did I have an obligation to say, ‘Wait a minute. I think you are manipulating me, and I have to call your attention to the fact that I’m aware of this, just so you’ll understand you are not succeeding.’”

MacDonald’s lawyer, Gary Bostwick, swooped on the switch in McGinniss’s behaviour. To some, it may appear axiomatic that a journalist is not a friend, but Malcolm interviewed four of the six jurors in the case, reporting that they were worried by the slippage between friendship and journalism. “The part I didn’t like was when MacDonald let McGinniss use his condominium, and McGinniss took it upon himself to find the motive for the murders,” said one of them. “I didn’t like the fact that McGinniss tried to find a motive for a book that was a bestseller, and that’s all he was concerned about.”

Well-known writers including William F. Buckley Jr. and Joseph Wambaugh testified in support of McGinniss’ practices, but they did not fare well under cross-examination. In his closing argument, Bostwick said that the practitioners’ argument that they would do whatever was necessary to write their book was one that had been used by demagogues and dictators throughout history to justify their actions.

Journalists’ ruthlessness in pursuing news is hardly news: what made Malcolm’s work of media criticism “newsworthy” was that she put under a microscope a rarely discussed aspect of journalist-source relationships. Journalists sometimes present a friendly face to sources before attacking them in their news stories, but the process is quicker, cruder and less ethically complex than in long-form projects where practitioners must go beyond a dazzling smile and create a deeper level of trust with principal sources.

The evidence suggests MacDonald was manipulative and deceitful. But so, too, was McGinniss when he befriended MacDonald and sent him letters giving him the impression he believed in his innocence. The publishing contract might have protected McGinniss’s editorial independence but once he agreed to share his book earnings with MacDonald he had, in effect, signed a Faustian pact. He would have known that a guilty finding was always on the cards, and when that eventuated he would have had to share his royalties with a convicted triple murderer. McGinniss’ editorial independence was crippled by the financial agreement with his principal source.

Where few were prepared to defend McGinniss in that respect, the question of when journalists might be justified in deceiving their principal sources, and the nature of the fine line between trust and friendship, are murkier subjects. But although Malcolm’s brilliant insight identified a key aspect of the journalist–source relationship, a close reading of The Journalist and the Murderer reveals that she believes there are only two ways for such relationships to go: either seduction followed by betrayal or a relationship kept at a safe distance.

She aims to avoid the seduction–betrayal fault in her own work, she writes, by always putting the needs of her “text” ahead of the “feelings” of her sources, but then she observes that McGinniss’s decision to stop being interviewed by her freed her from any “guilt” she might have felt in portraying him harshly. Malcolm rightly excoriates McGinniss for deceiving MacDonald, but she does not seem able to envisage the possibility of journalists openly disagreeing with principal sources while continuing to work with them. She actually describes the journalist-source relationship as “the canker that lies at the heart of the rose of journalism,” about which “nothing can be done.”

NOTHING? In studying the work of a range of writers and interviewing Estelle Blackburn, David Marr, Margaret Simons and other prominent Australian practitioners, I’ve found that a good deal has and is being done about this thorny issue. Those embarking on long-form or book-length projects can negotiate relationships with their principal sources that take on elements of the kind of informed consent that is commonplace among ethnographers, for example. The practitioner and the principal source can work out the ground rules, including how much access principal sources give to practitioners, how much editorial independence practitioners retain and how to negotiate the inevitable tensions that will arise in balancing the two.

Most writers are acutely aware of Joe McGinniss’s dilemma but many have said that they were willing to confront interviewees if they disagreed with them over an issue or when they believed they were lying. “If I’ve got criticisms, I find it useful to lay them out and see how they respond. It’s all good material,” says Michael Lewis, author of numerous narrative non-fiction books including Moneyball and The Blind Side. Richard Preston, author of the bestselling book about an Ebola virus outbreak, The Hot Zone, says he has learnt the importance of remaining calm in the face of lies when he was interviewing FBI agents for another book-length project. The agents simply “point out contradictions between the evidence and the suspect’s statements,” he told Robert Boynton for his book of interviews with nineteen leading non-fiction writers, The New New Journalism.

Where Lewis’s stance appears essentially pragmatic and Preston has learnt an effective way to confront difficult sources, Alex Kotlowitz told Boynton he keeps in mind the needs of his readers. At one point when he was researching the death of a black teenage boy found floating in a river running between a black community and a white community in south-western Michigan, Kotlowitz was told by one black woman it was inconceivable the boy had tried to swim because “we don’t swim. We don’t run to the water.” Kotlowitz says the comment brought to mind a remark made on national television by Al Campanis, general manager of the Los Angeles Dodgers, that blacks lacked the natural buoyancy to swim. He says he had to challenge the woman’s remarks “because otherwise I’d be left thinking, as would my readers, ‘Why didn’t I ask her the next logical question?’ I’d risk losing my connection to my reader.” Equally important, these statements prompted Kotlowitz to think about why such views prevailed. “And I learned much of it had to do with the ambiguous place of rivers in African American history.”

Richard Ben Cramer, author of a massive account of the 1988 presidential election campaign, What It Takes, told Boynton he learnt from his newspaper reporting work in Baltimore that if he needed to criticise a source in print he should let the source know ahead of deadline. “One politician who was my friend was sent to jail because of what I and others wrote in the paper. But I told him what I was doing every step of the way… I told him he might want to tell his wife before it hit. And he appreciated that. He sent me gifts from jail.”

Perhaps even more bracing are the lengths that Gitta Sereny went to inform Mary Bell about the likely additional problems she would face if Sereny agreed to her proposal to work together on a book in which Bell would give her account of how, at the age of eleven, she came to murder two small boys in Newcastle, England. It was a shocking crime that appalled a nation; three decades later, Sereny, who had covered the original trial as a young journalist, was interested in understanding how children come to commit such terrible crimes and how they might be prevented in future. Before her death in 2012, Sereny’s career had been devoted to exploring particularly difficult subjects such as the lives of Hitler’s confidante Albert Speer and the kommandant of the Treblinka extermination camp, Franz Stangl. Sereny asked Bell:

Did she realise… that such a book was bound to be controversial? That people would think she did it for money? That both of us would be accused of insensitivity towards the two little victims’ families by bringing their dreadful tragedy back into the limelight and, almost inevitably, of sensationalism, because of some of the material the book would have to contain? Above all, did she understand that readers would not stand for any suggestion of possible mitigation for her crimes?

Sereny’s deep compassion for Bell is evident throughout her 1998 book Cries Unheard but she does not hesitate from confronting her subject when she believes she is lying or being manipulative.

It is entirely possible, then, for journalists working on book-length projects to disagree with their sources and maintain a working relationship. It could be argued that openness between practitioner and principal sources about the project and a preparedness to discuss areas of disagreement are barometers of good practice. It is not inevitable, as Janet Malcolm, argues that everyone will end up doing a Joe McGinniss, though I would not for a moment suggest that the pattern of seduction and betrayal is defunct.

Sadly, McGinniss appeared to learn little from his dissection by Malcolm’s rhetorical scalpel. Via his website, he continued to defend his account of the Jeffrey Macdonald case in Fatal Vision. While it should be said that the justness of Macdonald’s conviction continue to be contested and that at least some of his criticisms of Malcolm’s book carry weight, McGinniss’s reputation suffered in recent years, especially for his 1993 biography of Ted Kennedy, The Last Brother, which was slated by Jonathan Yardley, the chief reviewer at the Washington Post, as “a genuinely, unrelievedly rotten book, one without a single redeeming virtue.”

Among its many sins, according to Yardley, was that McGinniss had, without Kennedy’s cooperation or consent, written an interior monologue for the senator the night in 1969 when he drove off the bridge at Chappaquiddick after a party and his companion, Mary Jo Kopechne, was drowned.

Can authors of narrative non-fiction write interior monologues for their subjects? Well, that’s another thorny question for long-form writers and their readers. •