FOR MANY people the fall of the Berlin Wall on 9 November 1989 was the moment when communism in Europe came to an end. But important events were still to come, including the meeting between Soviet president Boris Yeltsin and his counterparts from Ukraine and Belarus in Belovezhskaya Forest on 7–8 December 1991, at which they proclaimed the end of the Soviet Union. And the main links in the causal chain had been fashioned years earlier.

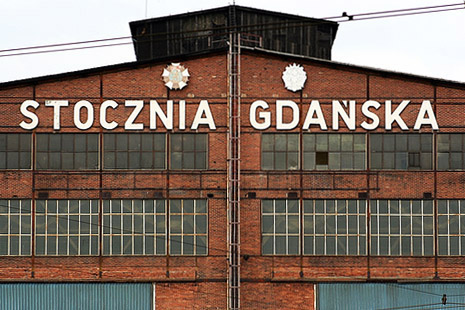

In August 1980, the outside world had watched with growing amazement as a wave of strikes swept across Poland. Such a comprehensive workers’ revolt had not been seen before in the Soviet bloc, not even during the Hungarian uprising of 1956. The strikers maintained a remarkable discipline, avoiding violence or other provocations, and the huge support they enjoyed in the whole country was palpable. On 21 August, just a week after the outbreak of the first strike in Gdansk, the authorities sent senior party emissaries to negotiate with the strike leaders. Within a fortnight, several wide-ranging agreements had been reached with key regions; within a month, a national free trade union federation called Solidarity had been established under Lech Walesa.

Events like these always seem inevitable in retrospect, and it’s difficult for younger people, especially those without experience of tough regimes, to comprehend just what would-be reformers of communism were up against. Most people on either side of the iron curtain feared that serious reform would not come without terrible bloodshed. Many found the prospect either unimaginable or too terrifying to contemplate seriously.

All previous attempts had ended badly: Berlin in 1953; Poznan in 1956; Budapest in 1956; Warsaw in 1968; Prague in 1968; and Gdansk and other Polish Baltic cities in December 1970. These events – particularly the crushing of the national uprising in Hungary in 1956 and the suppression by Warsaw Pact armies of Dubcek’s “socialism with a human face” in 1968 – left people feeling that all protest was ultimately futile. As a semi-dissident Polish group calling itself Experience and the Future said in May 1979, Poles had the “bitter conviction” that in the socio-political system they lived in, “radical change was absolutely necessary and at the same time totally impossible.”

But the transformation of August 1980 was less abrupt than it seemed. Poles had a long tradition of uprisings against Russian authority, and since the bloody suppression of the spontaneous demonstrations on the Polish Baltic coast in 1970, small groups of workers and intellectuals had been working together to prepare for the next round. After the Gierek regime again put down workers’ protests in several cities in 1976, dissident intellectuals formed the Workers’ Defence Committee to offer advice and support to working-class leaders. In 1979, the recently elected Pope John Paul II (previously the Archbishop of Cracow) returned to his home country on a visit that produced gigantic crowds across the country. Already the eerie consensus and exceptional discipline of future Solidarity mass demonstrations were apparent.

In the year or so after the agreements of September 1980, as Poles revelled in their new freedoms while the economy staggered further into crisis, the regime was forced to cede ever more ground to society. The workers’ demands, already quite expansive, became broader and more political. And the rest of Polish society joined in.

Communist one-party systems worked on a mixture of propaganda, intimidation, extreme concentration of power and the creation of elaborate structures of regime-controlled organisations designed to supplant and pre-empt genuine civil society. There were official trade unions, women’s groups, writers’ groups, student unions, publishing houses, professional associations and so on, all of them – with some Catholic exceptions – run by the party or its trusted nominees under tight central direction. Poland also had two parties ostensibly representing the peasantry and urban middle classes but in fact serving as top-down conveyor belts that did not dilute the one-party reality in the slightest.

Many of these phony bodies either were displaced by emergent Solidarity organisations or, in self-defence, began genuinely to represent their constituencies. Seeing these stooge organisations suddenly acquire real life was an odd experience, as unnerving – in the memorable phrase of the distinguished British journalist Neal Ascherson – as watching the ripening of wax fruit. The regime was progressively losing most of its instruments of power.

Even the party, security organs and army were influenced by the ferment, but they remained more fully under the leadership’s control than other institutions. As Solidarity’s demands for total democratisation became more insistent, the regime prepared its response. In October 1981, the defence and prime minister General Jaruzelski became party leader as well. With impressive secrecy in a society by then awash with information and opinions, he prepared a massive counter-revolution. Declaring martial law on 13 December 1981, he closed down nearly all communications and media for several weeks and “interned” thousands of Solidarity leaders all over the country. Solidarity, which had always been essentially an open and non-violent movement with little capacity for self-defence, was ill-prepared for this turn of events, and for several months seemed stunned.

But Jaruzelski, despite martial law, was not a gratuitously brutal leader or without patriotic scruples. In any case he realized, like Kadar in Hungary after 1956, that the regime could only be rebuilt on the basis of some modus vivendi with society. As normality returned, Solidarity revived both below the ground and later, increasingly, above it. A plethora of illegal, uninhibited publications burst forth. The movement’s leaders were gradually permitted back into the public domain.

During the 1980s, the economy, as in much of the Soviet bloc, went from bad to worse. Poland looked like a country where crises and revolts were perhaps only a price hike away. And with the accession of Gorbachev to the Soviet leadership, glasnost and perestroika were added to the mix.

As public resentment began spiking again towards the end of the decade, Solidarity reasserted itself, and in 1988 launched strikes and issued demands. Though the situation was less explosive than in 1980, the regime felt less able to resist or coerce. It agreed to commence in February 1989 what became known as the Round Table Talks, as a result of which partly free elections were held. Solidarity won with a crushing majority, which led by stages to the dismantling of the communist regime.

Solidarity radicals, a clear minority, were not happy that Walesa and his advisers had agreed to a negotiated solution that allowed the communist establishment to escape reprisals, squirrel away funds and, before long, stage a political recovery as born-again social democrats. The post-communists went on to win democratic victories, in large part by criticising the economic “shock therapy” adopted by the Solidarity government to transform the command economy and tackle the hyperinflation and other economic crises the communists had left in their wake.

The argument about whether the conciliatory Round Table approach was the right course has continued ever since, through all the kaleidoscopic mutations of parties and personnel in Poland’s volatile post-communist politics. But the results were good. The Polish communist establishment always had a strong liberal wing, which took to democratic politics skilfully and accepted the new dispensation. As a result, bloodshed was avoided both in 1989 and subsequently. But the argument among post-Solidarity politicians about who won the victory and who let the nomenklatura off the hook still rages.

As Poland became a normal, open society, the original raison d’être of Solidarity as a national all-encompassing body faded. Like that of the Catholic Church, its political influence has waned from the high point of 1989. While a Solidarity-led government held sway in the late 1990s for a time, the organisation has shrunk to become more of a trade union than a national cause or party, though it participates vigorously in Poland’s fractious politics.

SO WHAT is Solidarity’s legacy? During last year’s celebrations of the events of 1989, much public comment seemed to accept that the decisive moment in the fall of communism was the spontaneous demolition of the Berlin Wall. But the fall of the Wall, though spectacular and cinematic, was nonetheless a minor link in the causal chain. It came about in part by accident when a senior East Berlin official, Gűnter Schabowsky, sent a mistaken signal to the East German population that the Wall was about to be thrown open. And its dismantling had in any case been largely pre-determined when Gorbachev made clear that he would not bring tanks to the rescue of the regime, and when Hungary’s reformist communists decided to let East German tourists visiting their country escape en masse across the Hungarian–Austrian border.

In the downfall of communism, there were thus many causes and many heroes, most of them unsung, and some of them at first glance unlikely or indeed unintentional, like Schabowsky, or only partially intentional, like Janos Kadar of Hungary. Kadar’s decision to chart a liberal course after his brutal suppression of the uprising of 1956 enabled pluralism of a sort to develop in Hungarian society. Within Kadar’s Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party, a strongly reformist leadership group emerged that helped ease him into retirement, proclaimed the need for a “democracy without adjectives” and quite consciously set about undermining the East German regime.

Another partly unintentional hero, who remains sadly very much unsung in his own country, is Mikhail Gorbachev. Gorbachev came to reform communism, not to bury it. But it was his vision, political skill, courage, resolution and basic decency that not only transformed the system within his own country but also made it possible for reformers elsewhere, including in Poland, to achieve what they did.

Outside Russia, however, Solidarity’s non-violent example (compare Czechoslovakia and the Baltic states, for instance) was probably the largest single cause of the momentous events of the 1980s and early 1990s. Looking nostalgically back to Solidarity’s glory days, many Poles mourn the passing of an era of great national idealism and unity. But Solidarity’s contraction to more modest dimensions does not reflect tragic decay, just mundane democratic normality. And that too is an important part of its legacy. It would be good if all post-Solidarity politicians accepted that the age of righteous heroism has passed and that sweeping pronunciamentos are no longer required. •