The Dismissal Dossier: Everything You Were Never Meant to Know About November 1975

By Jenny Hocking | Melbourne University Press | $16.99

The Dismissal: In the Queen’s Name

By Paul Kelly and Troy Bramston | Viking | $39.99

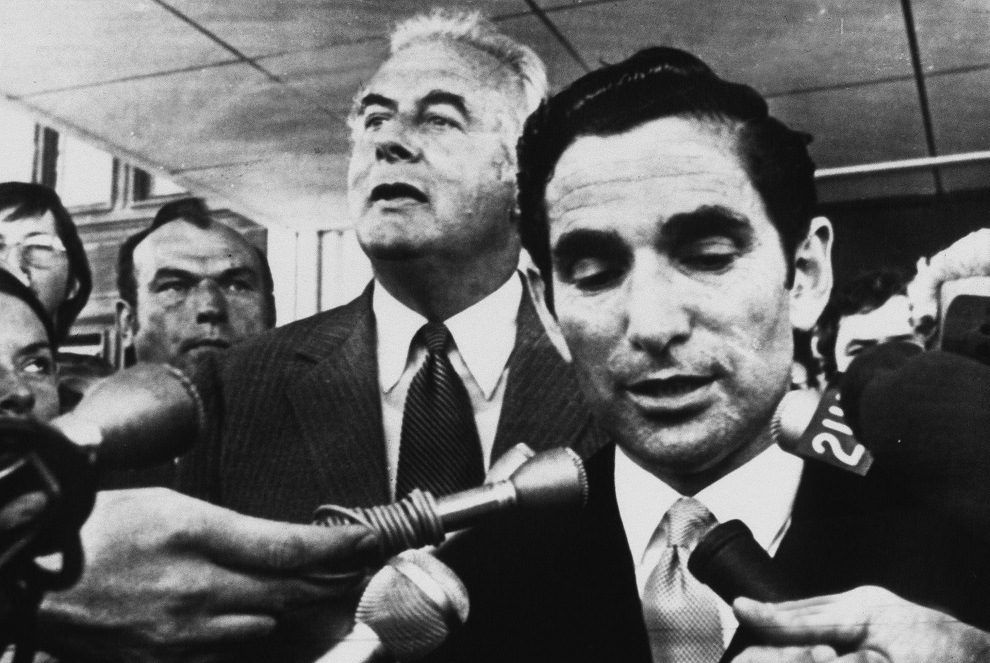

The dismissal of the Whitlam government by governor-general John Kerr is probably the most dramatic and controversial event in Australian political history. So it’s no surprise to find two new books published to coincide with the fortieth anniversary, each using previously unpublished material to advance an argument about what happened during the weeks before 11 November 1975.

In her slim book (at ninety-one pages, essentially an addendum to her two-volume biography of Whitlam), political scientist Jenny Hocking uses new material to argue that there was a conspiracy to overthrow Australia’s first federal Labor government in twenty-three years. In their more substantial contribution (310 pages, plus detailed appendices), journalists Paul Kelly and Troy Bramston access a wider range of sources, in Australia and Britain, and draw on new interviews with nearly forty participants in the crisis.

Hocking’s most contentious claims concern the role of Buckingham Palace. In his papers, Kerr claims that he was in written contact with the Queen and her private secretary, and in oral and written communication with Prince Charles, about the prospect of having to dismiss the Whitlam government. According to Kerr, the Queen expressed (via her private secretary) a willingness to “delay things” in the event that Whitlam pre-empted Kerr and sought to have Kerr dismissed.

But Kerr’s version of events, conveyed in a handwritten journal from 1980, is Hocking’s sole evidence for this point. Kerr, whose concern for his own tenure runs through the narrative, is hardly the kind of witness whom Hocking and other critics of the dismissal would normally use to advance their case. Indeed, his endless quest for self-justification should surely prompt any author to seek independent verification.

This is the approach taken by Kelly and Bramston, who have drawn on Kerr’s papers, interviewed Palace staff and used journal notes made by former governor-general Paul Hasluck, who discussed Kerr with some of those staff in 1977. Far from endorsing Kerr’s actions (let alone conspiring in them), Palace interviewees regarded Kerr as having acted prematurely; after the dismissal, indeed, the Palace was keen for his early departure from the post. As for a willingness to “delay things,” this appears to have been Kerr’s take on the Palace’s advice that his own dismissal could not simply be effected by a prime ministerial phone call to the Queen: documentation would be required. Kerr, by contrast, could dismiss Whitlam at the stroke of a pen. Instead of being reassured by the advice, Kerr remained obsessed about his own job security, and this was his main explanation for ignoring the Crown’s duty to warn the chief minister.

In her biography of Whitlam, Hocking has detailed the hitherto largely unknown role of High Court justice Anthony Mason in advising Kerr, especially in the period prior to the dismissal. This included, bizarrely, Mason’s organising of ANU law school members to tutor Kerr on aspects of vice-regal power (raising the question of why lawyers are appointed as governors-general if they have to drop by the local campus for a refresher course in Constitutional Law 101). Hocking now takes this part of the story further, revealing that Mason helped reinforce Kerr’s resolve on the afternoon of 11 November, advising him that the House of Representatives’ vote of no-confidence in the new Fraser government was “irrelevant,” a curious interpretation of a fundamental tenet of the Westminster system.

Hocking’s elaboration of Mason’s role leads her to conclude that chief justice Garfield Barwick was, in effect, the judicial fall guy – that he entered the drama (to advise Kerr) later than Mason but was prepared to take the flak in order to protect “the younger man” (as Kerr and Barwick cryptically described Mason). This protection was of no minor significance as it is scarcely conceivable that the Hawke government would have elevated Mason to the position of chief justice had they known of his role in advising and fortifying Kerr (as Hawke and several former cabinet ministers confirmed in interviews with Kelly and Bramston).

A vital feature of the constitutional crisis was Malcolm Fraser’s apparent confidence that events would unfold as they did. Did Fraser have private, unauthorised discussions with Kerr in the weeks before the dismissal? While Kerr and Fraser initially denied any pre-dismissal hints, both were later forced to admit to telephone contact on the morning of 11 November. Kerr maintained that he was merely establishing that the opposition’s position had not changed, but Fraser (supported by witnesses) claimed that Kerr had asked a series of questions relating to his being commissioned as prime minister. Only a fool or a sophist could deny that such questions presaged the imminent course of events.

In terms of earlier contact between Kerr and Fraser, Hocking considers a claim by former Liberal Senate leader Reg Withers (in an oral history interview in 1997) that he witnessed a phone conversation in which Fraser exchanged private phone numbers with someone who could only have been Kerr. This conversation, in early November, constituted a clear breach of Kerr’s undertaking to Whitlam that he would only contact or meet Fraser with the prime minister’s knowledge and approval.

Kelly and Bramston go back even further. They located a note of Kerr’s concerning a state dinner on 16 October, at the beginning of the crisis. In the note, Kerr records two detailed conversations with Fraser that night, at the end of which Fraser could have been in no doubt that Kerr’s fear of his own dismissal was a major concern, and that his trust in Whitlam was non-existent. These sentiments, improperly conveyed to Fraser, ensured that the opposition leader held a significant advantage over Whitlam for the duration of the crisis: he knew Kerr’s thinking; Whitlam did not.

Fraser denied that these conversations ever occurred, but Kelly and Bramston regard Kerr’s account as credible. Moreover, Fraser had form in this sort of fudging, having previously denied the phone call from Kerr on 11 November – until he was “outed” in 1987. A key theme in the dismissal saga is Fraser’s astute reading of Kerr, a complete contrast to Whitlam’s naive overconfidence and mishandling of the relationship. So confident was Fraser that on 6 November 1975, in an off-the-record chat with Kelly, he confided his belief that Kerr would sack Whitlam.

The least convincing part of Hocking’s case concerns Whitlam’s plan for a half-Senate election, which he proposed to recommend to Kerr on 11 November. She is convinced that had that election been called, opposition senators would have capitulated and supply would have been granted. But Fraser had advised Kerr that supply would not be available for a half-Senate election (only for an election involving the House of Representatives). It is of course possible (albeit not probable) that the announcement would have had the effect claimed by Hocking – just as it is possible that one or two Liberal senators might have caved in over the next few days even without the half-Senate election being called – but it can’t be treated as anything but speculation. This possibility is of such little consequence that it is not even mentioned by Kelly and Bramston, the former of whom was a Canberra press gallery member at the time.

In any event, there was a reason why Kerr would have been within his rights to question Whitlam about the proposal for a half-Senate election and, indeed, why he should have done so days earlier when Whitlam first signalled his intention. (By this stage, of course, Kerr had long passed the point of frank discussion with his prime minister.) Under section 12 of the Constitution, it is the state governors who “cause writs to be issued” for the election of senators from their states, and the conservative state governments, in support of their federal colleagues, had indicated their likely intention to advise their governors not to do so. Ironically, it was taken as a given that the governors would act on the advice of their chief ministers. Kerr could have sought to discuss with Whitlam the merits of approving a half-Senate election that might only take place in the two Labor states and in the territories. Kelly and Bramston are correct in asserting that any attempt to pressure the opposition with the threat of a half-Senate election would have needed to come at the start of the crisis, not at a stage when the exhaustion of government funds was such a live issue.

Interestingly, Hocking reveals Fraser’s admission (in an oral history interview in 1987) that securing supply was not a condition of his appointment as prime minister. Had supply not been secured, Kerr would still have allowed him to proceed to the 1975 election. This revelation should at least render largely irrelevant the speculation about what Labor senators might have done on 11 November to frustrate the passage of the budget by the new government.

Both books deal with the parliamentary drama of the afternoon of 11 November, as well as Kerr’s indifference to the passage of a no-confidence motion in the new prime minister and his delay in granting the speaker an audience until the parliament had been dissolved. One wonders what Kerr thought Whitlam would do after his dismissal: go away and write his election campaign speech? He certainly appears not to have anticipated Whitlam’s parliamentary tactics. Any expectation that Kerr would recommission the dismissed prime minister was surely misplaced, though, as this would have involved deceiving Fraser on a grander scale than Kerr had deceived Whitlam. It was gripping parliamentary drama on ABC radio that day; it would surely have been brilliant television.

Together, these books add to our knowledge of the most controversial event in Australian political history. Kelly and Bramston’s is the more important contribution, but they observe that lack of access to key materials (especially relating to the Kerr–Palace communications, vital to evidence the collusion claimed by Hocking) still hinders a more complete understanding of the crisis and its resolution. Broadly, access to a range of relevant documentation will be denied to the interested researcher until at least 2025 and 2037. This is completely unsatisfactory, and Kelly and Bramston deserve support in their representations to the federal government to overturn these embargoes.

There is much in both books to reinforce the view that Kerr behaved dishonourably in misleading and deceiving his prime minister. Even dismissal supporters such as Anthony Mason were adamant that a warning should have been provided to Whitlam, advice Kerr chose to ignore. And Kelly and Bramston do well to remind us that, in contrast with his soft left persona in post-parliamentary life, the Fraser of the constitutional crisis “engaged in the serial smashing of conventions that had long underpinned stable government in Australia” and “resorted to a mixture of persuasion and intimidation in the quest to have Kerr dismiss Whitlam.”

Thus, for some readers of a certain vintage, forty years after the dismissal, there is still reason for some rage to be maintained.