What a Life! Rock Photography by Tony Mott

State Library of New South Wales until 7 February 2016

Alphabet A–Z Rock ’n’ Roll Photography: Some Rock, Some Roll, Some Other Things!

By Tony Mott | Tony Mott Photography | $90

Two exhibitions held over the northern summer – one at the annual photo festival at Arles in France, the other at the Photographers’ Gallery in London – concentrated in different ways on the changing nature of music photography. Is it, as many fear, turning into a closed shop? Or is it going through a healthy and reinvigorating process of democratisation? Is it a dying art, being killed by the cult of amateurism, or is it reinventing itself and opening up new opportunities for talented photographers?

The exhibition at Arles, Total Records: The Great Adventure of Album Cover Photography, emphasised the historical link between the illustrated sleeve and the disc inside, both of them physical objects, the one contained within the other, the aural within the visual. The curators decided to show the album covers, some 600 of them in all, complete with overprinting and artwork, rather than the images alone, thus making the point, if it needed to be made, that the covers are artefacts from another age. The message on the archived website is clear – the age of the LP cover, the second half of the twentieth century, was a time when “photography mattered more than anything else,” and when there was a clear and mutually reinforcing link between the image and the sound: “looking at an album cover, you can almost hear what you see.”

It’s a definition of music photography – the image evokes the sound –that raises as many questions as it answers. Indeed, the very term “music photography” contains an implied question mark. How, in the end, do you photograph music? The implication of the Arles exhibition is that the direct link that once existed between photograph and music, so characteristic of the late twentieth century – when you could look at an album cover and hear what you saw – is now lost among a complicated mix of new technologies, new business models, new ways of listening, and changing notions of stardom, both photographic and musical.

In London, We Want More: Image-Making and Music in the 21st Century concentrated on the originality and inventiveness of the past fifteen years of music photography. As the exhibition’s website notes, “The traditional frameworks that once upheld a distance between photographers, fans, stars and their labels have collapsed to allow for new routes and territories in which music photography is produced, shared and consumed.” Musicians now routinely commission or enter into direct partnerships with photographers, not simply recording or ratifying a musical identity controlled from elsewhere (typically the record labels or that catch-all category of “management”) but rather partnering with the photographer to take charge of building and regularly rebuilding the visual brand. In contemporary music photography, the image does not so much evoke the music as concentrate on the endlessly fascinating subject of performance itself, on what it means for a musician to create and sustain a visual, as much as an aural, identity.

While some would lament the disappearance of a traditional system of financial and creative support for photographers – magazines buying and commissioning photographs, labels using images to create identities for their music – We Want More sees the change as essentially a good thing, empowering photographers, musicians and audiences alike. Instead of being bound to the commercial priorities of the magazine or the label, photographers “are now more in control of context and creative direction.” It’s a new world, in which everyone – the musician, the photographer and the audience – has a share in creative control.

Writing in the August issue of the British Journal of Photography about her experience of putting the exhibition together, the curator Diane Smyth notes how the final display seemed to fall of its own accord into two halves, one containing images of musicians and the other images of fans. As photographic access to musicians becomes ever more controlled, aspirational photographers turn their attention, almost by default, to photographing the audience. Rather than leading to second best, there may be a sense in which audiences are the new big subject, as photographers, almost invariably fans themselves, explore the nature and the attractions of fandom. Just as Lady Gaga, to take an obvious example, dresses up, then so – crucially – do her fans, turning themselves into photographic subjects.

In other words, the golden age of music photography is over and isn’t coming back, or another golden age has just begun, fuelled by the shifting relationships of musicians, photographers and audiences. Take your pick. At first impression, What a Life! Rock Photography by Tony Mott seems to plump squarely for the former. Along with a comprehensive photobook, Tony Mott’s Alphabet A–Z Rock ’n’ Roll Photography, published to coincide with the exhibition, this enjoyable and lovingly constructed overview of Mott’s work makes clear that there was indeed a golden age, that it peaked during the 1980s and the early 1990s, and that Tony Mott was very much at the forefront.

Less convincingly, the notes to the exhibition adopt an elegiac tone that sits rather oddly with the life and energy of the photographs themselves. For the curator, Louise Tegart, Tony Mott’s highly successful four-decade career has been due to a happy conjunction of talent and the times, and the times have been changing. “Rock photographs,” she remarks in the free broadsheet catalogue that accompanies the exhibition, “have become harder to sell now that everyone at a concert has a digital camera or a mobile phone. The scene has become more competitive, and skill levels have gone down.”

The rock journalist Toby Creswell puts the same sentiment more trenchantly in an entertaining essay in the catalogue. “Now everyone is a photographer,” Creswell laments. “Perhaps there is a Tony Mott app. Music is everywhere. Everyone is a critic and everyone is a musician so the world has become flooded with amateurism.” It is a familiar argument – photography mattered once, but it doesn’t quite matter any more, largely because everyone is doing it and standards have slipped. Against this gloomy assessment is the belief that there will always be opportunities for talent to make a mark, no matter how many people are taking photographs or making music (or writing, for that matter, another creative activity in which the lines between amateur and professional have become increasingly blurred).

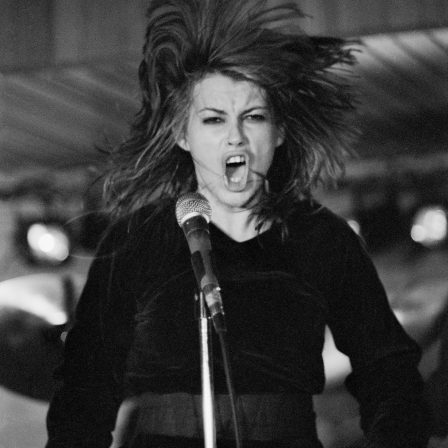

Tony Mott was born Anthony Moulds in Sheffield in 1956. By the early 1980s, after a peripatetic decade working mainly as a chef, he settled in Sydney and began spending all his free time combining his twin interests of music and photography. “On Monday nights,” Tegart tells us, “an unsigned band, the Divinyls,” featuring the then pre-legendary Chrissy Amphlett, “had a regular gig and twenty-eight-year-old Tony started to take photos of the band in action.” Mott recalls of this period that “for four months, I practised, on Chrissy Amphlett, the art of rock ’n’ roll photography.” One of his images of Amphlett – in Mott’s judgement, “the greatest female performer in the world” – was taken up and used by the Divinyls as a publicity poster, and Tony Mott was on his way from being an enthusiastic amateur to an in-demand professional.

To mark the happy conjunction between his twin obsessions of photography and music, he changed his surname to Mott, after what was and still is his favourite band – Mott the Hoople. By this act of homage, Mott was signalling his own fandom, marking himself as someone who could record the world of rock music from the outside while simultaneously being totally immersed in it. What this has meant in terms of recognisable style is an approach that is deferential in the best sense, allowing the personalities of the subjects to come through without the art-directed look of much rock photography of the 1970s and 80s.

The digital revolution, when it came, had little initial effect on Mott’s practice. When he did embrace the new way of doing things (if embrace is the right word), it was an unsettling experience. Speaking of images he made of Rihanna in 2008, he recalls that it “was the first gig I shot with a digital camera. I was shocked I got so many great shots that I had a sense I was cheating.” Elsewhere, he has referred to digital photography as “too easy,” rather reinforcing the idea inherent in the construction of the exhibition that something irreplaceable about photography has been lost.

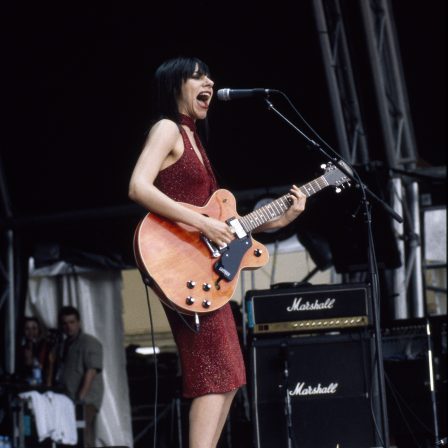

And yet, by providing this opportunity to look at Mott’s work as a whole – a mood-lifting mix of album and magazine covers, posters and flyers, interspersed with a large sampling of individually mounted images – the exhibition also shows how Mott’s work prefigures the casual, seemingly accidental approach that is characteristic of much digital photography. And on the evidence of the more recent images included in the exhibition, Mott has not lost his touch. He has responded to changes in the industry by taking on more work in film and television, but he also continues as a practising music photographer. The recent in-concert shot of P J Harvey (2011), fighting back against the visual weight of her guitar and the microphone, keeps drawing the eye, and an image of Daniel Johns, taken this year against a characteristic background of blurred, post-industrial grime, is a model of sympathetic portraiture. “He looks wise,” Mott comments of Johns in this image and he’s right, he does.

But simply being sympathetic, and involving subjects as collaborators, doesn’t always work. In Mott’s offstage photographs, there can sometimes be a bit too much face-pulling on the part of the subjects, which is meant to signal spontaneity but can come across as contrived. Mott is aware of the risks. He aims for naturalness and a strong sense of the individuality of his subjects, and can be hard on his own work if he feels that it does not meet these criteria. His portrait of the Clouds from 1999 has an intriguing air of formality that contrasts with the majority of the images on display, the backdrop curtain evoking a photographic studio – unusually for Mott, who generally prefers “found” locations. (Taken “at Central Railway Station,” he says of his 1996 image of Smudge, “as good a location as any.”) The plain, unpatterned clothing worn by the two members of the band in the left of the frame forms a satisfying visual contrast with the two on the right, both of whom sport more striking patterns. Yet for Mott, this image, perhaps because of its suggestions of deliberate construction, doesn’t quite work. “I shot the Clouds many times for Australian and US record companies,” he remarks in the wall notes, “but never felt I captured the essence of the band despite my love of ’em.”

Like all professional photographers, Mott had clients to please. In a funny and self-deprecating talk delivered at the State Library of New South Wales during the opening weeks of the exhibition, he referred to the standard and clichéd shot, often favoured by magazines, of the musician’s hair swirling in the air, the kind of shot he has taken on more than one occasion. His photograph of Lenny Kravitz (1994), displayed in the exhibition in larger than life-size format, in which Kravitz’s expression seems to suggest a high degree of self-consciousness about the hair, is a good example. “A bit of a Hendrix wannabe,” says Mott, in an unusually astringent comment. On the other hand, in that early image of Chrissy Amphlett from 1983 (“the first photo I ever sold”) the wildness of Amphlett’s hair seems at one with her look of total, unselfconscious absorption in the song. The thing about standard shots is that sometimes they work.

Mott’s photographs eschew glamour. Certain kinds of backgrounds occur again and again. Often they seem random in the extreme – a security grille, a brick or a sandstone wall, a sick-looking shrub. For location shots, he favours empty theatres or run-down railway stations or the disused warehouses that were common in the former industrial areas of Sydney in the 1980s. “Taken in a derelict warehouse in Chippendale,” says Mott of his 1997 image of the band Front End Loader, a warehouse “that was destined to become another block of flats like so many buildings I’ve used as backdrops.” Often the background, in the onstage and offstage images alike, is so blandly unglamorous as to be unidentifiable, appearing either blacked out or blurred. When Mott uses recognisably iconic structures – the Harbour Bridge or the Opera House or, in the case of a 2010 photograph of Angus and Julia Stone, the Harbour Bridge and the Opera House – these photogenic feats of architecture and engineering are made to seem ordinary, somewhere on a par with a brick wall.

Mott’s world is almost exclusively urban, but he does occasionally photograph his subjects against a natural background. “It is a dramatic setting,” he says of a 1988 shot of the Venetians in which the band is standing in front of the Kiama blowhole, but in fact this dramatic setting looks more like a painted backdrop, against which the band members stand out all the more. “We were waiting for a beautiful sunrise,” Mott comments laconically in Alphabet, “but it never happened.” This characteristic downplaying of the background encourages the viewer to concentrate on the main subject.

In his group shots, Mott elicits the personalities of each of the band members, who will often be positioned at some distance from one another. In some of the images – The Vines (2003), for example – each individual occupies a different depth of field. Yet despite this internal distancing, these images still manage to convey a strong sense of interconnectedness. In the Vines’ portrait this effect is enhance, as in many of his other images, by Mott’s use of a favourite device, the fisheye lens, which helps to link the band members by placing them on a continuous curve and enclosing them within the same visually distorted space.

For Mott, the photographic encounter is generally a positive experience. As we learn from the wall notes to the exhibition and from the captions in Alphabet, the musicians Mott photographs almost invariably impress him as likeable and funny and charming, even on the occasions when he doesn’t necessarily expect it. Lou Reed, for example, is “surprisingly pleasant company.” There is no reason to doubt these positive assessments, but they also suggest something about Mott’s manner as a photographer and his ability to put his subjects at ease. Unlike actors or professional models, musicians may not feel comfortable with the camera, or even like having their photograph taken at all, particularly when they are starting out on their careers. “Relaxing them is imperative,” he says in Alphabet.

Mott’s capacity to draw the best out of the musicians he photographs is evident; the exceptions all the more striking for their rarity. “My father always told me,” he says in the wall note to his 1992 image of the Beastie Boys, “if you have nothing positive to say about someone say nothing, so what I’d like to say about the Beastie Boys is…” The ellipsis is Mott’s. Yet even without the benefit of the commentary, the effect of the image is less than warm. A stretched-out, sneakered foot takes up the bottom half of the frame; the Beastie Boys themselves adopt poses that are both defensive and aggressive. And yet, for all that, it is an effective composition, demonstrating that a bit of tension, between difficult subjects and a photographer who maintains his equilibrium, is not necessarily a bad thing.

One of the many inspiring aspects of this exhibition is how Mott’s vast portfolio of photographs reflects the many definitions of success. His subjects range from superstars to musicians whose fanbase never extended much beyond inner-city Melbourne or Sydney. “Why, oh why are they not bigger?” he asks of You Am I. The same question could no doubt be asked of many photographers, then as now. By his own account, Tony Mott did not set out with a deliberate strategy of becoming a successful rock ’n’ roll photographer. Instead he set out to pursue his twin enthusiasms for music and photography, and by a combination of commitment and good fortune and, of course, talent, was ready to grab the opportunity, when it came along, to turn himself into a professional.

He didn’t so much fall into photography (an expression commonly used by people when reflecting on their successful careers, and almost never exactly true) as throw himself into it, becoming so absorbed in the intricacies of his chosen medium that it took somebody else to show him he could make a successful living out of it. It is probably the case, as the exhibition catalogue suggests, that there is little chance of quite such a scenario developing today in quite the same way, when the competition is greater and ambition is more conscious and more overt. Yet there are still many photographers who manage to break through from amateur to professional, navigating new commercial realities and distribution platforms to get their work out there. And in that respect, though the times were different then, Tony Mott’s work provides a template. •