Almost eighty years ago a small New York publishing house put out a new book of cartoons by Saul Steinberg, then a rising cartoonist at the New Yorker. That volume, All in Line, initiated the career of one of the most puzzling of all twentieth-century artists — one whose unclassifiable work included six other books, innumerable drawings and paintings on every imaginable subject, a series of spectacular murals, and many wildly successful exhibitions on both sides of the Atlantic. At the time of a retrospective in 1978 the critic Harold Rosenberg argued that the questions raised by Steinberg’s work unsettled the accepted bases of the aesthetic realm. This remains true: Steinberg’s work dragged the idea of art — Art with an honorific capital letter, the art of the galleries, museums, collectors, and critics — under the shadow of an enormous question mark (a favourite Steinberg motif).

A new edition of All in Line, published by New York Review Books with an introduction by the cartoonist Liana Finck and notes by the Saul Steinberg Foundation’s Sheila Schwartz, offers viewers the chance to catch Steinberg as he sets off on a mid-century journey that would be punctuated by delight, surprise, and many an unexpected jolt. This is my afterword to this new edition.

— Iain Topliss

Saul Steinberg’s All in Line was a triumph when it was first published in June 1945. The New York Times praised it, there was a positive notice in Art News, and LIFE magazine reproduced examples of the drawings with comments from the artist (making a drawing “is… like walking along an edge… if you lean in a little too far… you are lost”). In the first month of publication alone it sold around 6000 copies. There followed a second printing, selection by the Book of the Month club, and a Penguin Books (London) reprint on austerity paper for distribution in Great Britain. Within a year Steinberg reported sales of 20,000. In 1947, Penguin Books (New York) issued a much-modified paperback edition with a bastardised cover image for the American popular market. Already well-published in the United States, Steinberg stood on the brink of what would develop into a truly brilliant career.

All in Line emerged from a tumultuous phase in Steinberg’s life. In 1933, following the rise of nationalist and anti-Semitic politics in his native Romania, Steinberg moved to Italy to train as an architect at the Regio Politecnico, Milan. While there, he found his gift as a comic artist, publishing to acclaim in two humour newspapers. But the promulgation of racial laws by the Italian fascist state in 1938 made him an outcast, and by 1940 he was seeking refuge in another country.

Following a six-week internment in a camp on the Adriatic coast in spring 1941, he spent a year in the Dominican Republic awaiting a US visa. In February 1943, now in New York, he received a commission as an ensign in the US Naval Reserve (along with American citizenship), thanks to the machinations of New Yorker editor Harold Ross, already an admirer of Steinberg’s work. Then, after a six-week layoff in Calcutta, he served fifteen months in China, North Africa, and Italy assigned to the propaganda arm of the Office of Strategic Services. By early October 1944 he was back in the United States. Although he remained on active duty for more than a year, eventually being promoted to the rank of lieutenant, his war was effectively over.

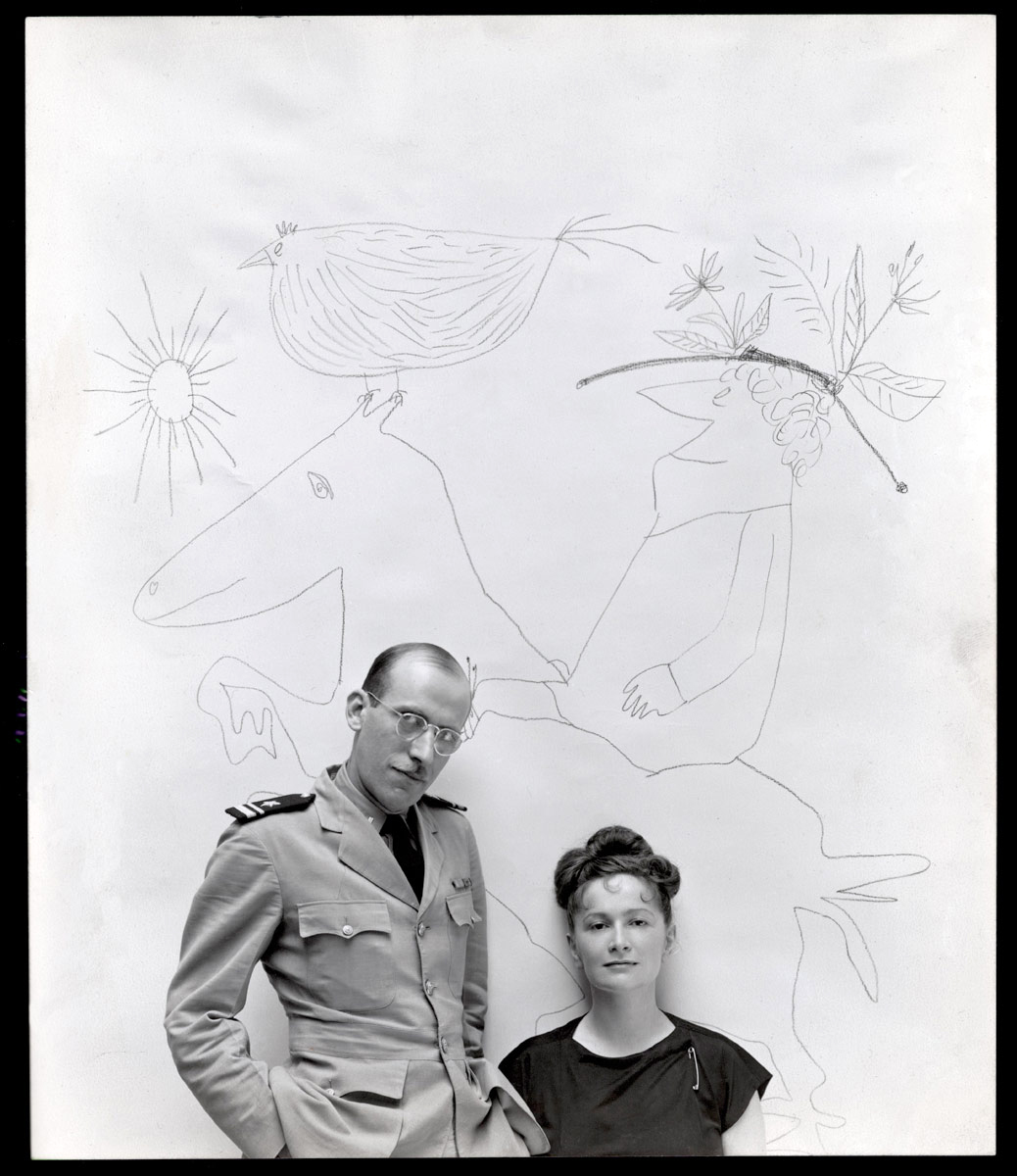

Steinberg and Ross apart, three other people helped in the making of All in Line: Victor Civita, at the time acting as Steinberg’s agent; James Geraghty, art editor at the New Yorker; and Hedda Sterne. Sterne, a fellow Romanian expatriate who was making her way in the New York art scene, agreed to take care of Steinberg’s artistic interests during his absence overseas. She and Steinberg had already begun a tentative love affair.

Civita’s role was a vexed one. In an October 1943 meeting with Sterne in New York and later in letters to Steinberg in China, Civita gave the impression that he had come up with both the idea for the book and the publishers, Duell, Sloan & Pearce. Months later, Sterne found out it was the other way round — the publishers had thought of the collection and contacted Civita through Geraghty. This small deception was typical of Civita’s way of pushing himself forward. The publishers couldn’t bear him, Sterne disliked his “noisy vitality,” and Geraghty complained he didn’t think “the way we do.”

Steinberg had more serious reservations. He told Sterne that Civita had insisted “the only way of being able to publish something in New York is just lowering the standard… make a vulgar ‘popular’… kind of drawing.” “Civita,” Steinberg wrote later, “doesn’t know but business for himself… interested only in money.” (Like Sterne, Steinberg’s English at this time was far from perfect.) Nonetheless, it was Civita who, one way or another, drove the project along, making preliminary selections, securing the cooperation — often qualified — of the others, dispatching proofs, and helping fend off a rival publishing offer from Alfred Knopf, one favoured by Geraghty. Negotiations with Knopf continued after the Duell, Sloan & Pearce contract had been sent to Steinberg, but although that contract was dated 17 January 1944 it was probably not signed until later, by which time Knopf was out of the picture.

As first proposed, the book would collect the best and most popular of Steinberg’s work of the previous four years, from satirical, anti-fascist war cartoons in PM and Liberty, which he had begun to publish while still in the Dominican Republic, to humorous “idea drawings” in the New Yorker. Steinberg disliked the hint of retrospectivity in such a selection. He wanted more recent work and opposed the inclusion of anything suggestive of an earlier “European” lack of sophistication, such as characterised, he believed, his work in Italy in the 1930s and even some later drawings.

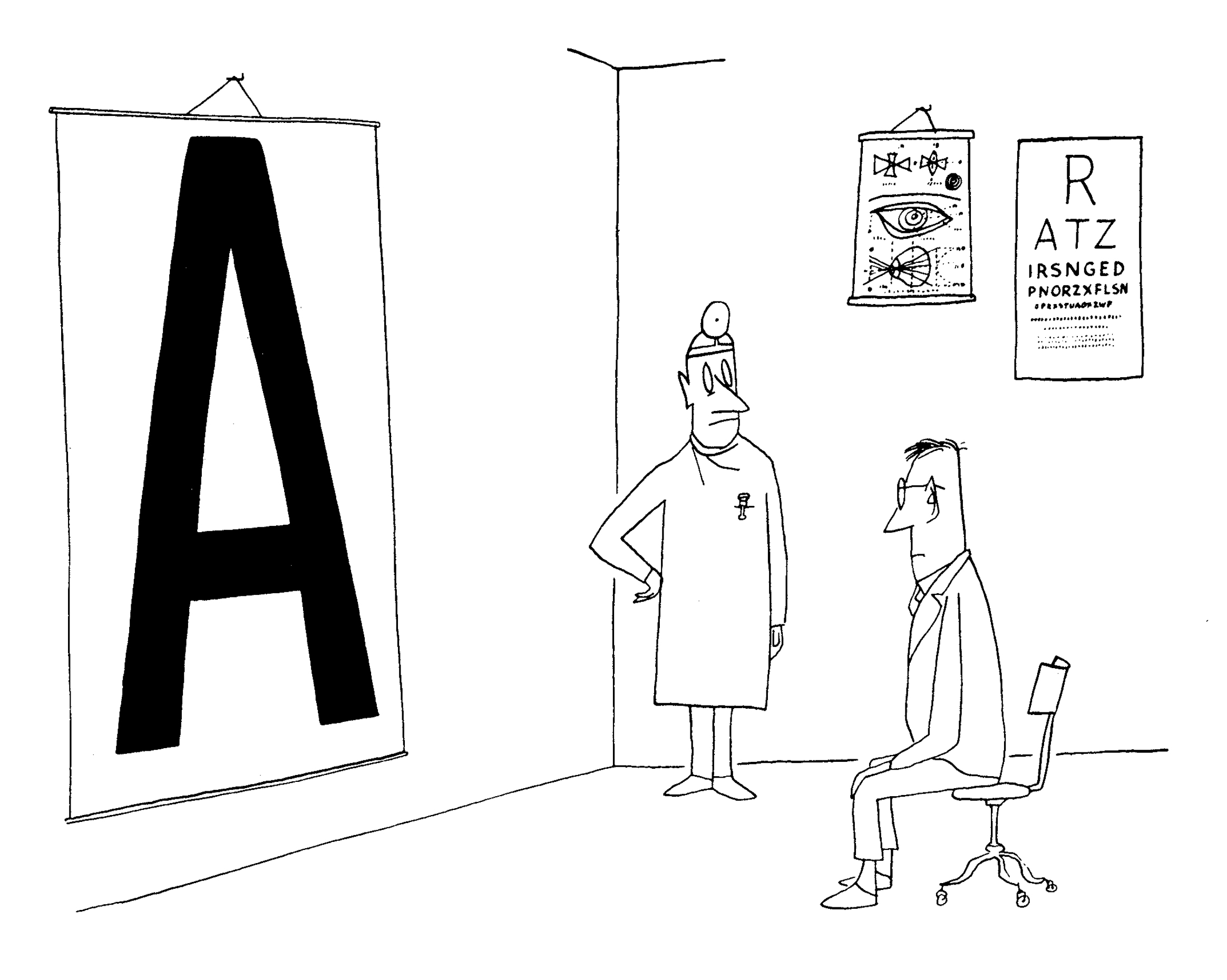

One instance was the picture of the optometrist asking a client if he could read a floor-to-ceiling-height letter A. Both Civita and the publishers thought it should be included, and Sterne, on pragmatic grounds, agreed. Steinberg did not. “It’s an old old drawing,” he complained, “made maybe two years ago or more, when I made transition from my european style to The New Yorker’s and it sure is a very stupid drawing… drawings like [this] don’t do me any favor.” But as Sterne pointed out, it had attracted much fan mail, and despite Steinberg’s misgivings, was a fair example of his work.

Steinberg relented. The drawing stayed, but he redrew it to make the people look more “American.” For most viewers the difference between the “European” figures in the New Yorker version (30 October 1943), and the “American” ones in All in Line will be easily missed — modifications to pose, body shape, and facial features — but for Steinberg the shift was critical.

During the book’s gestation, Steinberg was on the move — from China to Algiers, from Algiers to Naples, then back to Algiers, and finally to Rome. Frustrated by the slowness of the mail, fretting that Civita “would make some silly combination,” he despaired of ever having a final layout to approve. After getting one roll of thirty-five-millimetre film with more than eighty drawings on it, as selected by Civita and apparently agreed to by Sterne, Steinberg was livid: “Now I’m sure… Civita influenced [you] on choosing the worst drawings… [but] the selection is very casual… I told clear that I don’t want old ones and political and more than half is made out of old and political.” Sterne defended the selection: “If there are cartoons which everybody thinks wonderful… you might put them in even if as a work of art you don’t like them much — People will buy the books and see the ones you like too.” Eventually, unconvinced, Steinberg told Sterne he was sick of the book and thought it best “just to wait.”

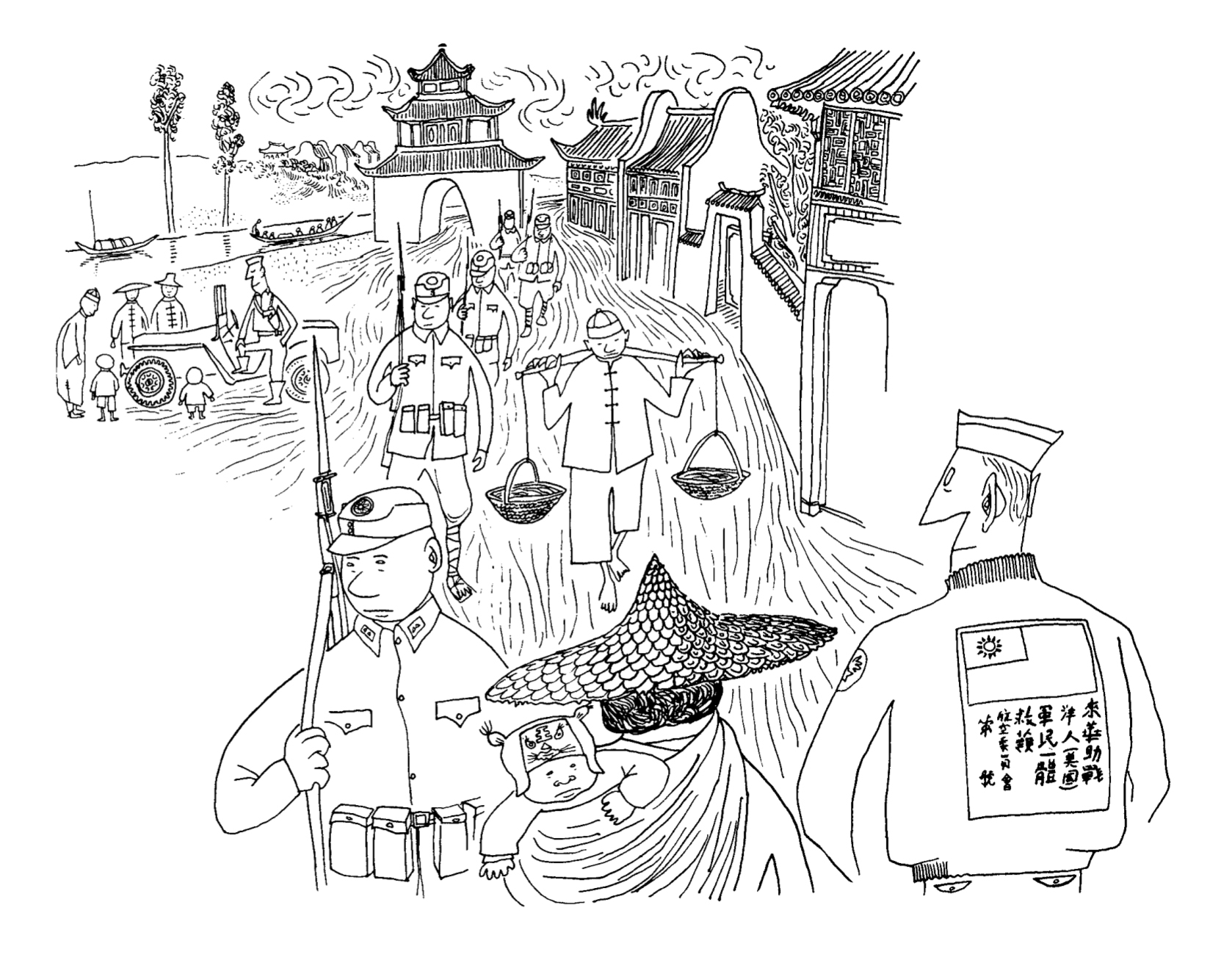

Steinberg’s frustration arose not just because he disagreed with Civita’s selection, but from a revelation of what his powers as an artist might amount to. Back in August 1943, after six weeks in a training camp in southwest-central China, Steinberg was posted to Kunming. In his spare time, he drew studies of life in the town. “I made about a dozen… Very special drawings… rather different from my usual. I act like a photographer and sketch what I see… I sit down and sketch with thousands of people around looking behind the shoulder. It works.”

In these drawings he avoided both the overt political character of the anti-fascist cartoons published earlier in PM and Liberty and the wild comic inventiveness of his other works, instead recording off-duty military life and encounters with the local populace. The Kunming drawings were reportage, mimetic but not straightforwardly so, freighted with the artist’s idiosyncratic touches. They were unlike anything he had done before.

By late October he had sent off “thirty to forty” of these drawings to The New Yorker, including the one below. Six weeks later, the drawings arrived, and Ross and Geraghty were overjoyed, promising to publish them in a two-page spread as soon as possible. Once the drawings appeared in print Ross declared them “the strongest pieces of art we have run in a long time… everybody is jubilant about them, including the readers.” Gratifyingly, they were noticed in Washington — “a lot of Air Force people… spoke of [them] proudly, including the Under Secretary of War for Air.”

Steinberg’s war drawings solved a problem for Ross. From its inception, the New Yorker had refused to publish photographs, but after nearly two years of fighting the magazine’s reporting still lacked a visual dimension. The contrast with the pictorial magazines — LIFE, for example, very much on Ross’s mind — was painful. Ross told Steinberg: “Our coverage… in drawings is largely by ear” — that is, pictures drawn by staff artists from descriptions provided by correspondents — “and therefore not as good as we would like to have it.” But with Steinberg’s drawings the magazine not only recovered ground but even gained an advantage over its rivals — “You may save the day for us, in a big way… the hell with LIFE and the other magazines,” as Ross put it. The first of three China portfolios was published on 15 January 1944.

By early February 1944, it occurred to Steinberg that he had material for two books: the book Civita, Sterne, and Geraghty were working on, and a separate book of war drawings. Ross had much the same idea but pointed out that the war drawings would have to be published before the war ended, which he thought could be within months. Steinberg digested this advice. Mindful of how unsatisfactory Civita’s selection had been, he was tempted to abandon the first book altogether, telling Sterne in April, by which time he had been in North Africa and Naples, “I think I better give up the idea of making a book of drawing — I’d rather make one of war drawings which can be ready in a couple of months, some 70 drawings would be allright.” As for the compilation of his humorous work, he continued, “the selection made by Civita is more than one half wrong on my opinion, and I’m sure he didn’t care much for your opinion… So I think war drawings will make a better union or unity.”

It seemed as if the book of witty drawings was doomed. But Steinberg then began to wonder if the war book might not be improved by the addition of a few carefully selected humorous drawings. In the same letter, he then said: “maybe a better idea would be to call the book ‘Soldiers & Civilians’ and include a second part of just a few, about 20… of caption-less… usual stuff.” This sounds like a preliminary version of All in Line. By June, he had changed his mind a third time, returning to the idea of two books. “I’ll take a decision tonight,” he wrote to Sterne, “probably for lack of a better idea I’ll say yes. The hell with it, let’s have books.” This seems definite — “books” not “book” — but from this point on the idea of two books vanishes, never to be heard of again.

Steinberg returned to the United States on 4 October 1944. He and Sterne married a week later (he had proposed back in January in a series of letters and illustrated “newsletters”). He could now manage the book himself, having in hand drawings from all the war theatres in which he had served. Details are not clear, but it is fair to assume that the final choice of drawings and the layout was Steinberg’s alone. His hand is certainly evident in the title. Late in the game, it was still Everybody in Line, as suggested by Duell, Sloan & Pearce over a year earlier. That remained the title in a sketch of the dustjacket Steinberg made in his appointment book on 17 February 1945. But in another such drawing on the 30 April page, it had become All in Line.

The 1945 edition of All in Line is arranged in two parts. First, a forty-eight-page untitled collection of Steinberg’s humorous drawings, many from the New Yorker. Second, a seventy-two-page section, “War,” divided into five sub-sections: some of Steinberg’s propaganda cartoons from PM and Liberty, followed by portfolios based on his double-page spreads in the New Yorker —“China” (15 January and 5 February 1944, and 24 March 1945), “North Africa” (15 and 29 April 1944), “Italy” (10 June, 8 July and 29 July 1944) and “India” (24 February and 28 April 1945).

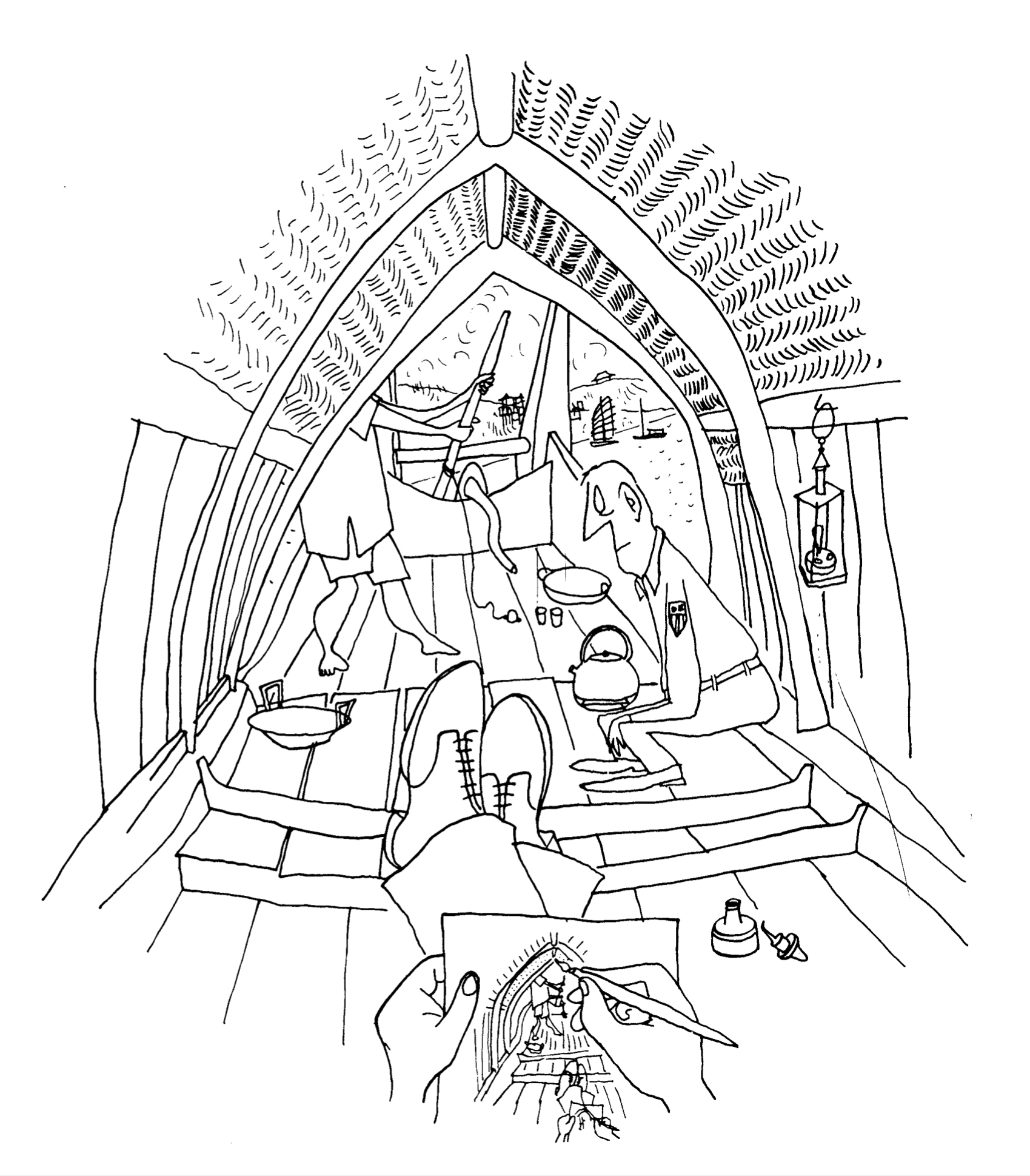

To “War,” Steinberg added many unpublished drawings, contrasting, for instance, the splendid view of the servicemen in a transport plane flying over the Himalayan Hump with a similar view of the inside of a sampan on a river in China (above). He also used six pages of unpublished Italian sketches, notably a view of the border checkpoint between Rome and Vatican City, a panorama of an occupied Italian provincial town, and a view of Vesuvius erupting, a scene Steinberg had witnessed. In some of these war drawings, we can detect a private meaning.

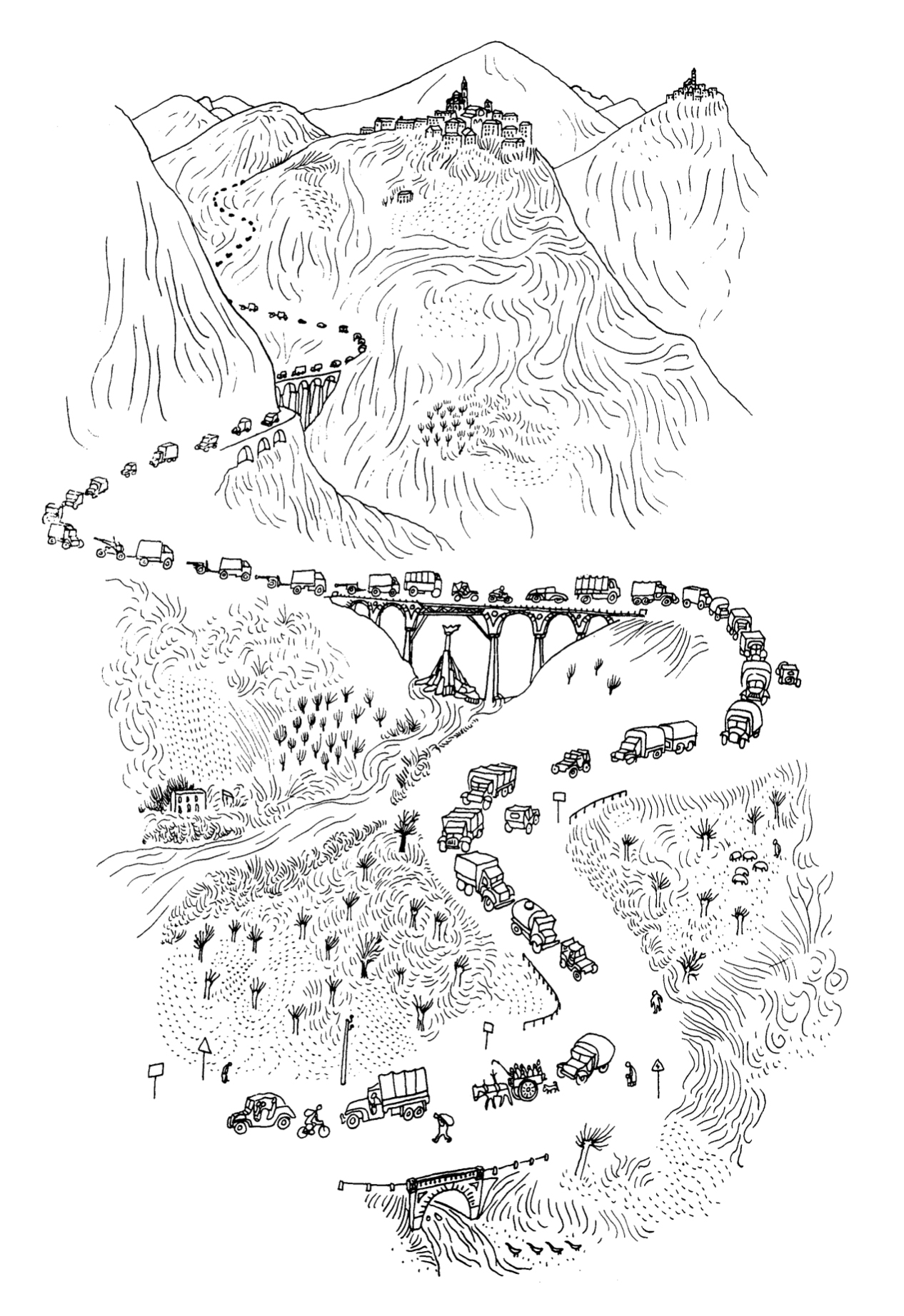

One addition to the “Italy” portfolio, the drawing he chose to head the selection, alludes to an earlier moment in Steinberg’s life: the obelisk in a piazza with figures is a topographical fantasia, privately dated on the original drawing “Friday June 6, 1941,” that far-off day when Steinberg, then in an Italian internment camp, heard that he would be freed and permitted to leave Italy. Similarly, in gratitude to Harold Ross, Steinberg’s American begetter, he made sure that the book would close with a drawing Ross had singled out as his “favorite,” the convoy in the mountains:

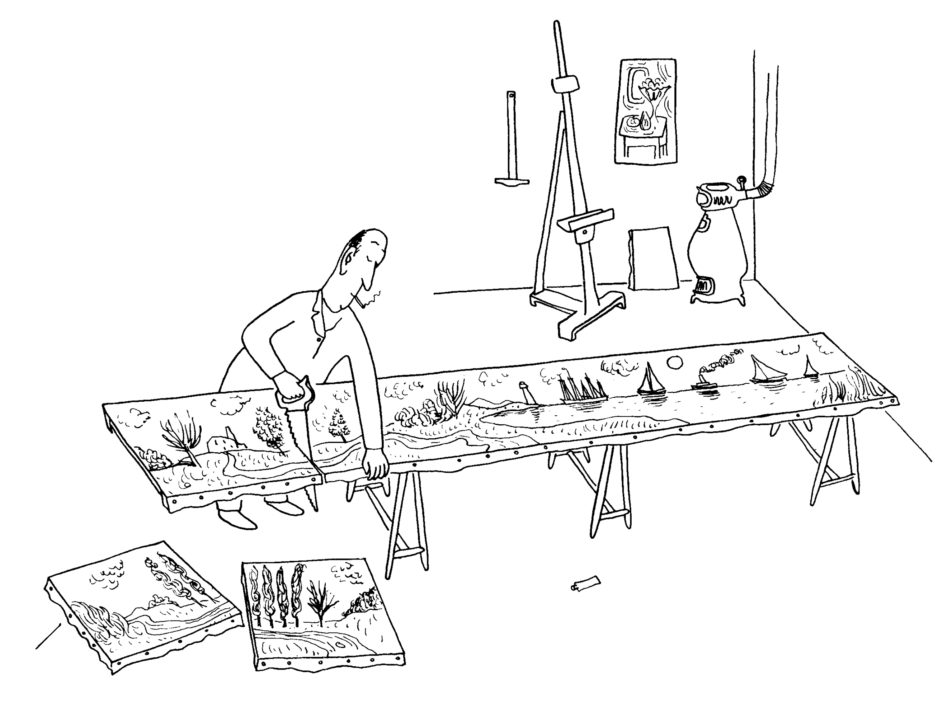

Walter Bernstein’s review of the book in the New York Times pointed out that the best drawings were those “without captions, that do not fit the regular cartoon formula.” He singled out a clock eating itself as time passed, an idea that had “the terrifying quality of the best surrealist work.” This quality is discernible in drawing after drawing: the elaborate doodles of the end-papers; a painter sawing an extended landscape into sellable units (below); a smoker blowing smoke-squares; a man asleep with his shoes, gloves, watch, spectacles, and hat laid out, each in its anatomically correct place, on the floor beside his bed; the counter-intuitive tilt of the horizon in a picture of a GI’s sea voyage.

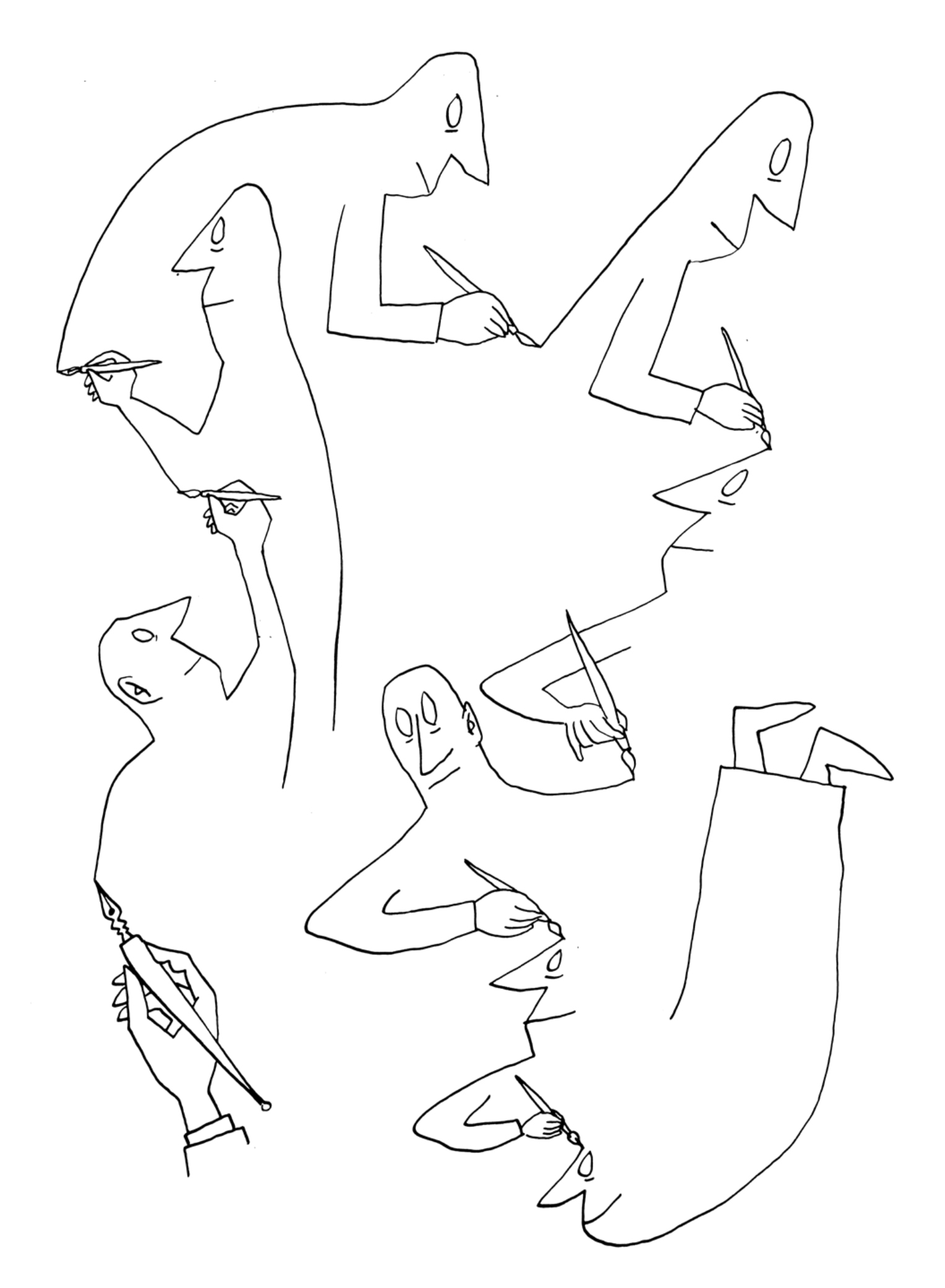

Steinberg later understood that this sort of effect — the discovery of the unexpected in the familiar, the redeployment of a received idea, an adjustment of scale or perspective, lay at the heart of his work. “I… have always thought that to express certain things I had to transform them into jokes, puns, or… strangeness: so-called humor.” That transformation is epitomised in this drawing of Steinberg drawing Steinberg drawing Steinberg, a motif that even finds its way into the scene inside the sampan.

The drawings in All in Line have a vivacity springing from Steinberg’s exceptional, often startling wit, but they provoke something greater than a passing comic delight. “Your humor is poetry,” Sterne wrote to Steinberg during the planning for All in Line, “because its mostly a tender smile upon things one never looks twice at — Instead of taking away the magic of things that have it — you add where there is none.” The special “poetry” of Steinberg’s humour, as singled out by Sterne, is but one sign of something more momentous, the arrival of a new late-modern sensibility, one that embraced the taking of liberties with habitual ways of seeing and the gleeful dissolution of old forms and fixities.

The range is extraordinary: from bizarre comic drawings (a mis-constructed centaur), to savage political satire (Hitler, a pistol to his own head, orders Mussolini, Hungary, and Romania at gunpoint into Russia, dragging along behind him a child-size Finland, above), to eye-opening visual reportage (a street scene in unwrecked Kunming, also below). It is hard to think of any other artist at the time who could put together such a collection. These drawings extend the viewer’s horizons — whether comical or conceptual, political or geographic — and presage the reach of Steinberg’s later work. •