Although it’s only three months since Swedes last voted, the minority Social Democrat–Green government has called fresh elections for March next year – the first time the country has returned to the polls this early since 1921. The decision came after the four-party centre-right Alliance voted against the government’s budget, and the far-right Sweden Democrats added its weight to the anti-budget majority. Rather than resign and leave the Moderates to attempt to get their own budget passed, the government chose to continue as an interim administration and call new elections.

This is further evidence that Sweden is not following the familiar three-step pattern since the Sweden Democrats performed unexpectedly well in this year’s election. When a right-wing party wins a large swathe of voters with populist rhetoric about national unity and attacks on immigrant cultures, centre-right parties usually try to take the wind from its sails by adopting some of its rhetoric and taking a harsher position on immigration. Left-of-centre parties, meanwhile, often reduce their commitment to multiculturalism. The combined effect is to shift the political spectrum to the right.

The first step came when the Sweden Democrats more than doubled their vote and their seats in the parliament at this year’s national election. What has stopped the mainstream parties taking the next two steps?

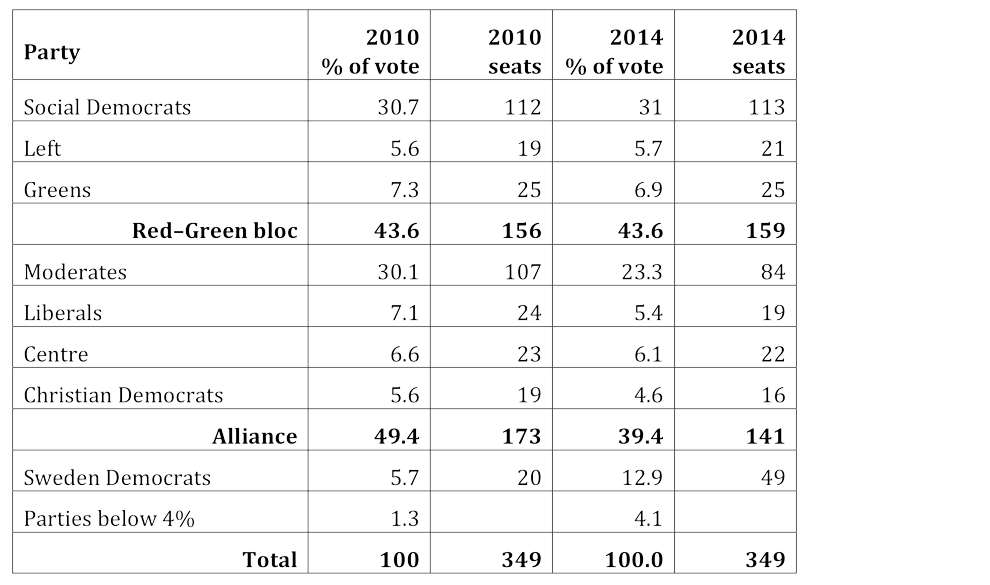

One answer has to do with the way the Swedish electoral rules encourage small parties to develop around the Social Democrats on the left and the Moderates on the right, as the chart below shows. These small parties have obvious Australian parallels. The Left Party resembles the left faction of the Australian Labor Party, which in turn resembles the Social Democrats. The Liberal Party resembles the “wet” wing of our Liberal Party, which largely resembles the Moderates. The Centre Party resembles our National Party, and the Christian Democrats, inspired by the Germans, are something like Australia’s Democratic Labor Party. On the left, a new micro party, the Feminist Initiative, narrowly missed the 4 per cent threshold for parliamentary representation in the September election. The Social Democrats will be banking on the feminists clearing the hurdle in March, or collapsing altogether; either would be better than a narrow failure, which would see crucial left-of-centre votes go to no party at all.

Swedish election results 2010 and 2014

Source: Wikipedia

The Sweden Democrats stand outside this pattern. As neo-fascists, they are more like the National Front in Britain or France, even if they also use much of the vague and populist rhetoric favoured by Pauline Hanson and, more recently, Clive Palmer. Their level of support among voters means that they can only upset Sweden’s bipolar party system to a limited degree.

But there is a deeper answer to the question of why the mainstream parties are resisting the influence of the far right, and it has to do with the history of Swedish public policy and the way it is anchored in the country’s institutions and interests.

The Swedish manufacturing sector has always been strongly export-oriented, and there is a longstanding consensus about free trade. A cosmopolitan perspective on immigration prevails among the employees of Sweden’s large, export-oriented manufacturing firms. Many of these employees travel the world for work, and they were a key part of the majority vote – supported by unions, employers, the Social Democrats and the Moderates – to join the European Union in 2004.

Compared to the more nationalistic Denmark and Finland, Sweden opened up to multiculturalism strongly in the 1970s. Social Democratic prime minister Olof Palme could not plausibly advance international peace without more multiculturalism at home. Sweden shifted from net emigration to relatively high rates of immigration, which drove economic growth much as it has done in settler societies like Australia, Canada, Israel and New Zealand. But within that pattern of immigration and population growth, consensus about refugees has been fraying at the edges.

Sweden has had a more liberal refugee policy than the settler societies since the 1970s. It has accommodated large numbers of refugees, who enjoy full citizenship in a welfare state that still has relatively high taxes and many universal benefits. This changed in 2008, when the Conservative government fell into line with EU restrictions on refugees and loosened some of its rules about family reunion (which were traditionally tighter than Australia’s, for instance). Since the emergence of high unemployment in 2002, pockets of Sweden’s larger cities have experienced high unemployment among immigrants along with problems of public order and policing. The famous footballer and Swedish captain, Zlatan Ibrahimović , who was born to Bosnian and Croatian refugee parents, grew up in one of these problematic suburbs in Malmö. These are the districts where the Sweden Democrats have won seats in local councils and now in the national parliament.

While a Red–Green government is unlikely to return to a strongly pro-refugee policy, it will continue to defend the ethos of multiculturalism. Like the centre-right Alliance, it will adamantly resist the far-right demand to reduce overall immigration rates. Despite the problems of high unemployment and poor integration, the mainstream consensus is strongly anchored in the political economy of an export-oriented manufacturing sector. There is every reason to expect that the mainstream parties will continue to resist the second and third steps of a general rightward shift of the political spectrum. Exactly how this plays out in the 22 March 2015 elections will be interesting to see. •