At the opening session of the annual Economic and Social Outlook Conference, hosted last week by the Australian and the Melbourne Institute, Productivity Commission chairman Peter Harris expressed surprise that no one issue seemed to have sufficiently dominated public debate in recent months to become the focus of the conference.

Really? I wonder if he still thought that at the end of the conference – by which time opposition leader Bill Shorten had flagged further policy shifts by Labor to tackle tax avoidance by those at the top, and the Australian had quoted the Melbourne Institute itself to declare Labor’s narrative about inequality “patently false.”

With Shorten tipped to announce a Labor commitment to crack down on tax avoidance through trusts when he addresses the NSW Labor conference this weekend, treasurer Scott Morrison has clicked into gear, wheeling out the usual “the politics of envy” line that you hear whenever anyone suggests making the tax system fairer. Morrison would have had the phrase ready to hand because it’s been thrown at him when he’s tried to do the same.

This issue has the potential to be a key battleground between the parties all the way to the next election. Shorten looked comfortable and relaxed as he staked out his ground. Fairness is not an issue uppermost in the minds of the conference’s hosts, but it certainly is one that concerns the electorate, and there is no shortage of statistics to suggest that voters’ worries are well-founded.

It was the issue that dominated the conference. Malcolm Turnbull’s lunchtime speech was unmemorable, Scott Morrison’s dinner speech confident but free of anything new. Shorten and shadow treasurer Chris Bowen are much luckier: they have a party united behind them and can take bold moves without fear of a knife in the back. They had the opportunity to set the theme for the conference, and they did.

Whatever you think of this or that presentation, this regular conference is now a great institution for national debate. It amply justifies the vision of its founders, former Melbourne Institute director Peter Dawkins (now vice-chancellor of Victoria University) and former Australian editor (now columnist) Paul Kelly. While this year’s conference was marred by a security overkill that became a pain in the neck, the debates made up for it. It’s to be hoped that the institute will soon have the presentations online so everyone can share the benefits.

As always, the conference covered a wide variety of issues. Foreign minister Julie Bishop put down predictions of future Chinese supremacy with a swathe of statistics and a spirited declaration that “the United States will, for the foreseeable future, remain the dominant power in the world.” While artfully dodging any commentary on President Trump, she told us: “I have to say, I am very impressed with Secretary [of State] Tillerson and [Defense] Secretary Mattis. They are pragmatic people, and much of my optimism about the Trump administration comes as a result of my meetings with the leadership of the state and defence departments.”

Environment minister Josh Frydenberg and his Labor counterpart Mark Butler showed that bipartisanship on climate policy is within our grasp, trading compliments as they joined in warning of the seriousness of the immediate crisis facing energy-intensive manufacturing, and highlighting the stunning speed with which the costs of solar power and battery storage are falling, potentially providing a long-term solution.

My take from the session was that Frydenberg is deadly serious about tackling the gas exporters to force prices down. “Our aim is to get back to a network price of $8 to $10 a gigajoule,” he told us. If he succeeds, it will be a huge relief to the gas-intensive manufacturing plants now being quoted double that price for new contracts.

Professor Bob Gregory of the Australian National University, one of Australia’s most original and respected economists, issued a blunt warning about the risk of long-term budget deficits. He pointed out that the thin surpluses Treasury forecasts for the 2020s assume that income tax will be allowed to rise to the highest levels for decades, relative to gross domestic product, or GDP, and that many pensioners will have been pushed off full pensions onto part pensions. “Will that happen?” he asked incredulously. If so, it would lead to “growing populism and dissatisfaction in Australia.” If not, it would mean we will not see the budget surpluses now forecast.

Professor Guay Lim, head of the Melbourne Institute’s macroeconomics team, argued that we should be more worried about private debt – which has now soared to more than 200 per cent of household income, the fourth-highest share in the OECD – than public debt, which is only a fraction of that level. She challenged the Reserve Bank’s assurances that all is well because most of the debt is held by high-income households. Rather, as she showed, debt has risen rapidly among households rich, middling and poor – and at the extreme, 25 per cent of unemployed households now have debts more than treble their incomes.

But perhaps we should still be worried about the budget debt, in the light of Gregory’s warning that the assumptions of future surpluses are politically implausible. Grattan Institute director John Daley caused great hilarity with artful graphs contrasting Treasury’s forecasts of year after year of soaring tax revenues with the very modest rises actually achieved. The bottom line, however, is that Australia is now running one of the biggest budget deficits in the Western world, and if we keep on that path we certainly will end up with a high government debt.

Which goal should have priority: tightening the budget to deliver a genuine return to surplus by 2020–21, or stimulating our weak economy in the hope of delivering the growth that will do it for us? Chris Bowen, the man most likely to be treasurer in 2020–21, dodged the question by making a genuflection to “good quality structural reforms.” If Labor wins office, he will have nowhere to hide. In last year’s campaign, his proposal to claim fiscal virtue by making savings over a ten-year period was gutted by Labor’s decision to allow the deficit to blow out even higher in the short term.

Bowen’s speech brought together the themes of fairness, fiscal virtue, and Labor’s readiness to lead with bold reforms on both fronts. “Tackling inequality will be the defining mission of the Shorten Labor government,” he declared. OECD figures, he said, show that Australia gives away more in tax concessions than any other nation – and that excludes negative gearing. He hinted at new policies to tackle geographical inequality, saying that half of all jobs created in the past ten years were within two kilometres of the Sydney and Melbourne GPOs.

If “populism” was the word some conference speakers used to put down opponents, that was lost on Bill Shorten. Fairness was front and centre of his speech, which he delivered twice – first, of course, to the media, on Thursday night, and then eventually to the conference itself, over lunch on Friday. He highlighted the evidence of growing inequality in Australia, across many indicators, but especially low wage growth, then zeroed in on the “two-class” tax system.

As he described it, Australia has an “economy class” tax system, which serves that “vast bulk of Australians,” the pay-as-you-go wage-earners, and offers them, at best, “a couple of vanilla deductions” for salary sacrifice or work-related claims.

“But then there is the ‘business class’ tax system. Beyond the curtain. Where a different tax menu is served,” he went on. “A whole different set of rules for people who are fortunate to have the financial wherewithal to mine the plethora of choices for aggressively minimising their tax. Significant property portfolios, complex deductions, parking the money in offshore tax havens…

“Now almost all of this is perfectly legal. But when a nurse on $50,000 asks why someone who earns twenty times more than they do pays less in tax – saying ‘it’s legal’ is not satisfactory.”

As far as I recall, neither Bowen nor Shorten specifically mentioned the privileged tax treatment of family trusts, perhaps the core tax lurk by which farmers and wealthy Australians have dodged tax for decades. Inquiry after inquiry has recommended that trusts and partnerships should be taxed the same as companies, but no government has been game to do so. The word is that Labor is now prepared to bite the bullet on this – perhaps with the consolation of knowing that those affected will find that companies, too, have lots of ways to dodge tax.

In fact, there was no specific discussion of trusts, and no session on tax reform, during the conference. But the Australian chose to lead its conference report with a rather puzzling speech by the institute’s deputy director, Professor Roger Wilkins, who declared that “the narrative that says inequality is ever rising is patently false… If anything, inequality has been declining.”

Given all the data to the contrary, that’s a big claim. Yet the only evidence Wilkins presented for this was the institute’s long-running HILDA study, in which several thousand households track their financial progress. HILDA reports that the proportion of respondents earning less than half the median income has shrunk from 13 per cent to 10 per cent since the start of the century. I am no specialist on inequality, and he is, but that’s a remarkably thin basis for such a sweeping claim.

First, it essentially measures how pensioners are faring relative to the average wage-earner: that’s all. We know that pensioners have done relatively well in the past twenty years: the Howard government indexed pensions to average weekly earnings, ensuring they couldn’t be left behind, and the Rudd government gave them a big increase in 2009.

But anyone following the debate knows the central issue is that average wage-earners have been doing badly. There is a mountain of evidence for that, some of which I chronicled recently. If Wilkins’s claim is correct – and the Bureau of Statistics data tells a different story – it would only confirm Labor’s narrative, that average wage-earners are falling behind.

Second, Wilkins conceded that one reason why HILDA’s findings are different from those of the Bureau could be that each year 4 per cent of its respondents drop out. Over time, that could do serious damage to its ability to serve as a microcosm of Australia – particularly if, as with the Australian Election Study (which I examine here), those who drop out of the survey are mostly those at the bottom of the socioeconomic pile. HILDA was a great initiative, and remains a valuable source of data on those families that fill out its form – but claims that its macro data represents Australia today should be treated with caution.

Third, Wilkins didn’t dispute the figures on which Labor bases its claim that inequality is at a seventy-five-year high: that the share of income going to the richest 1 per cent of Australians is now the highest in the postwar era. His own figures start from 1970, but reach the same conclusion.

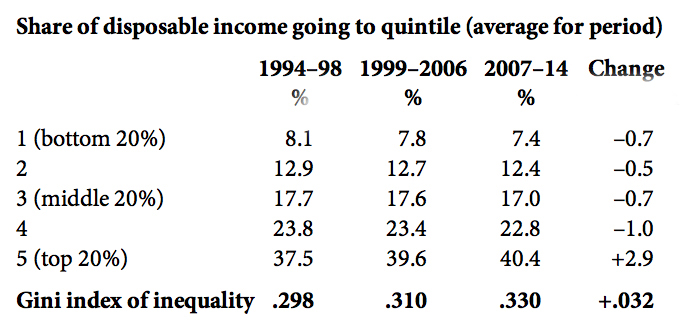

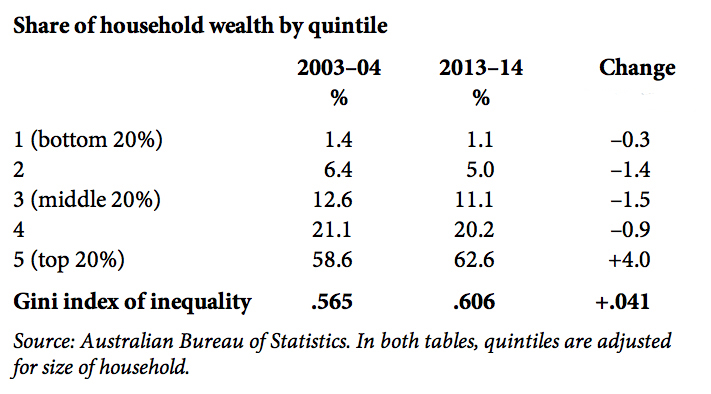

That, too, is a single statistic. A better measure is the Bureau’s biennial survey of household income and wealth, which charts the financial details of 14,500 households over a year. To make its data even more robust, I have grouped the findings of several surveys together, and the trend is very clear. The top 20 per cent of Australians have increased their share of income and wealth substantially in recent years, at the expense of all other income groups. Here’s the data:

Is inequality declining?

Not according to income…

Nor according to wealth…

Wilkins cautions that the Bureau has changed the design of the survey over the years – for the better – but the changes he mentioned seemed to cut both ways. The Bureau’s next report, for 2015–16, is due next month. Whatever it adds, its figures over the previous twenty years clearly show that inequality in Australia has risen, and significantly.

The share of income going to wage-earners is now at its lowest level for more than fifty years. In the five years to March, the disposable income of Australian households grew by $187 billion; their collective debts grew by $575 billion. The storm clouds over the economy are growing darker, and it will take a combination of boldness and self-discipline by policy-makers, and a large dose of good luck, for Australia to come out of the bursting of its real estate bubble unscathed.

Shorten is fortunate that he does not have to look over his shoulder. And today’s Newspoll finding that Coalition voters prefer Turnbull over Abbott by a massive three-to-one majority should leave the PM free to stop looking over his shoulder, and focus on doing what needs to be done.

Tackling inequality would be good for the economy, and for the Coalition’s election prospects. It should become part of his government’s defining mission too. •