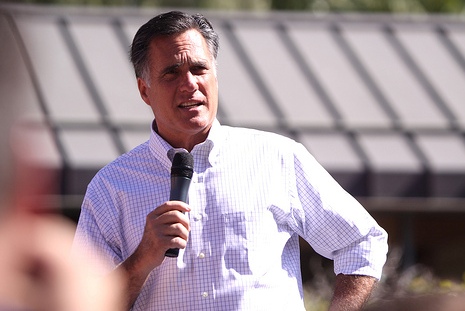

WITH Mitt Romney now the putative Republican challenger to Barack Obama, the focus of the campaigns, the pundits and the pollsters has shifted from the primaries to the general election in November.

One American pollster estimated recently that there has been about one presidential election opinion poll a day over the past two months. RealClearPolitics lists twenty-nine such polls over the past two weeks, and between now and the election the numbers will mount into the hundreds. While political pollsters have clearly established a reliable income stream, have they provided us with any useful insights into the likely results in November?

Obama leads in the majority of polls released since Romney effectively became the nominee in March, but as the other Republican contenders disappear, one by one, from the scene, the race is tightening. Romney has been a weak candidate to date, but if he can capitalise on voters’ concerns about the economy and conservatives’ visceral dislike of Obama and his policies, and if he can get out the independent and reluctant voters, then the contest is likely to be close and competitive.

The polls show that Romney faces a huge “likeability” gap against President Obama – a devastating disadvantage given that US presidential elections have often become personality contests. This means that Romney must turn the campaign into a contest of policies, not personality. Expect to hear Romney endlessly ask the 2012 version of Reagan’s 1980 challenge: “Are you better off now than you were four years ago?” now phrased as “Do you want four more years of Barack Obama’s policies and philosophies?”

But however much the polls suggest that large numbers of Americans are uneasy about Obama’s policies, they still like the man. And Romney is the least popular party nominee since Walter Mondale in 1984. Republican strategists contend that their candidate’s personal ratings will begin to rise now that the primary campaign, which has been characterised by negative ads and public antagonism among the candidates, is all but over.

It isn’t just the likeability gap; there is also a gender gap. One recent poll gives Obama a fourteen-point lead over Romney among women likely to vote in November’s election. And despite Republicans’ efforts to portray themselves as the party of the family, Obama has a big edge on family values among women, with 51 per cent picking him as stronger on that issue while only 36 per cent opt for Romney.

These numbers give Republican leaders pause for thought. But they argue that if Romney can ensure the 2012 race comes down to a decision about who is the most competent leader for a country facing tough economic times, he can still prevail.

There are suggestions that Romney’s wife, Ann, could help him close the gap with Obama. According to one poll, she is viewed favourably by 40 per cent of the public, 5 points better than her husband, and seen negatively by 30 per cent, 17 points lower than her husband’s unfavourable rating. But another gap looms between the wives: Michelle Obama’s favourability rating currently stands at 69 per cent.

The economy will be the top issue for voters in the election, and polls show the battle over which candidate is better equipped to handle it is up for grabs. Most Americans believe that Romney has better ideas for fixing the economy and is better on the deficit, but Obama is seen as better on jobs. Both candidates need to address the un-American air of pessimism that hangs over the nation, fuelled by the lagging economy, sluggish job growth, rising gas prices and concerns about federal spending and the budget deficit.

The fact is that neither candidate inspires confidence in potential voters. The nation sees Obama differently in 2012 than it did in 2008. More than three years of Washington’s polarised and uncompromising political environment has taken a toll on the image of the president who promised so much hope and change. It’s not clear if Romney could fare any better with Congress – even a Congress where both the House and the Senate are both Republican-controlled. The Tea Party conservatives in the House have shown themselves willing to take the country to the brink, in defiance of the GOP leadership, rather than negotiate, and virtually all Senate votes now require a super-majority of sixty.

While Romney pushes his business acumen, this is a two-edged sword for him. A majority of voters say that upper-income Americans pay less than their fair share of taxes – and last year Romney’s own effective tax rate was only 15 per cent. His wealth does not help his relationship with many voters, who think that he does not care about their needs and problems.

The tax issue – kicked down the road by Congress – will loom large in the presidential debates. The Obama team is already seeking to tie Romney’s economic platform to that of the Bush administration, arguing that the economic and tax policies Romney is advocating would repeat the problems that put the country into recession, exacerbate income inequality, and prevent middle-class Americans from getting ahead.

While most of his economic policies have worked, Obama is disadvantaged because their impact has not been large enough to make an obvious difference in many voters’ lives. He is left with the ineffectual argument that, without these policies, things would have been worse. That doesn’t play well in the swing states that are up for grabs.

A poll released yesterday shows President Obama leading in the twelve battleground states that will be critical in determining the outcome of the 2012 election, although Romney has made inroads among independents.

Some pundits claim that, typically, the incumbent president’s job approval rating on election day will be close to the share of votes that he receives. Obama's job approval rating stands at 50 per cent in the Gallup Daily tracking poll for 21–23 April. This is notable because all incumbent presidents since Eisenhower who were at or above 50 per cent on election day were re-elected.

But those who take heart from this and other modern political proverbs – “no president has been re-elected when the unemployment rate is over 8 per cent,” for example – should recognise that predictive data are in short supply. There have only been sixteen presidential elections since the second world war and every election is different.

In the end, national head-to-head polling means little, and elections are decided first in a handful of battleground states and then in the electoral college. The polls make for tough and focused campaigning and erudite but largely meaningless pontification on the Sunday talk shows. Read them with scepticism, even on 6 November. •