The Fox in the Attic

By Richard Hughes | Atlantic | $22.99

ON A sunny weekend in the summer of 1961, Britain’s secretary of state for war, John Profumo, together with his wife, the actress Valerie Hobson, were the guests of Lord and Lady Astor at Cliveden, the Astor family’s grand estate in Berkshire. It was a large party, with visitors coming and going throughout the two days; the president of Pakistan, en route for talks with the US government, was there for at least part of the time. Meanwhile, in a cottage on the estate, occupied on a grace-and-favour basis by the society osteopath Stephen Ward, another house party was in full swing. A group of Ward’s friends and acquaintances, including several London party girls and the assistant naval attaché from the Soviet Embassy, were enjoying a break in the country.

These two worlds might have remained quite separate, at least on that particular weekend, but for a chance meeting at the estate swimming pool, where Astor and his guests, taking an evening tour of the grounds, came across Ward’s party as they splashed and frolicked in the water. In the recently published An English Affair: Sex, Class and Power in the Age of Profumo, Richard Davenport-Hines describes John Profumo’s first, crucial sighting of the attractive, dark-haired woman who was shortly to become famous; she “had just lost her swimsuit or the bra part of her bikini in a prank, and had swathed herself in a towel. Forty years later, and not reliably, Profumo recalled that Astor slapped her backside playfully and said, ‘Jack, this is Christine Keeler.’”

As Davenport-Hines makes clear in his bleakly entertaining account of the scandal that arose from this chance meeting between a young girl and a middle-aged man who hadn’t grown up, the Profumo affair, as it unfolded over the next few years, marked the final, very public collapse of many things: of faith in the status quo and confidence that one’s betters know best, of routine deference to authority, of trust in institutions and the people who run them. The origins of the collapse could, of course, be traced back far beyond that Saturday evening in July 1961, to the general ham-fistedness and consequent humiliation of the governing classes over the Suez crisis, or to the social upheavals occasioned by the second world war, or to the sweeping away of Edwardian certainties occasioned by the first. Indeed, looking back now on the Profumo affair, it seems almost ordained that the agent of this explosive exposure of the weaknesses and hypocrisies of “the system” should, following in the footsteps of those earlier conflicts and conflagrations, have been the war minister.

For many writers of the period, the story of the twentieth century was already a story of things going wrong, of vast disparities between public and private behaviour and between the larger political sphere and the messy business of human relations. There was something of a fashion for looking at these questions through extended sequences of novels; in Evelyn Waugh’s Sword of Honour trilogy (1952–61), for instance, or Olivia Manning’s Balkan Trilogy (1960–65) or Lawrence Durrell’s Alexandria Quartet (1957–60) or, a little later, Paul Scott’s The Raj Quartet (1965–75). Mixing history and fiction, broad sweep and sharp detail, the focus of these multi-volume works is on individuals participating – often from the sidelines – in great events, their own loves and lives taking precedence over social movements and historical processes they do not properly understand and cannot in any case control. Among the less well-known of these forerunners to the boxed set – less well-known, perhaps, because it never got past the second of a projected three, four or possibly five volumes (reports vary) – is The Human Predicament, by Richard Hughes, the first volume of which, A Fox in the Attic, was first published in 1961 and has now been re-issued by Atlantic books.

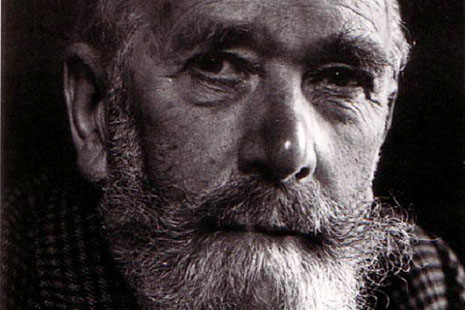

Richard Hughes was then, and remains today, best known for his first novel, A High Wind in Jamaica, published in 1929 when he was not quite thirty. A High Wind in Jamaica tells of a family of schoolchildren who are travelling unaccompanied from Jamaica to England when their ship is attacked and boarded by pirates. Deploying a complex set of narrative devices, Hughes creates a world that upends our expectations both of children and of pirates. To the consternation of many readers at the time, Hughes depicted the children as essentially amoral and ruthless, more than a match for the pirates. Hughes retained all his life a special affinity for children and for the child-like qualities in grownups, but it was a cool kind of affinity through which he also displayed his own streak of ruthlessness. His daughter Penelope Hughes begins her 1984 memoir of her father by recalling a game he played with her and her companions in a stream near where the family lived in Wales. “My father would hold his breath and count to sixty while we sat ourselves on arms and legs, and crowded onto his back. Then the earthquake would begin. He would roll us into the water brushing us off like gnats.” It’s an image, of human interaction and isolation coexisting with one another, of the kind that recurs repeatedly in The Fox in the Attic.

We first see the hero of The Fox in the Attic, Augustine Penry-Herbert, in a brilliant opening scene in which he is tramping across the Welsh sea marshes, carrying the corpse of a child over his shoulder. Augustine is twenty-three years old, of an age with the century. When news of the girl’s death by drowning spreads abroad, the mere fact that Augustine has discovered the body makes him, in the minds of the nearby villagers, somehow responsible; their hostility, and Augustine’s native restlessness, cause him to leave behind the great house he has inherited and travel to Germany to stay in the Schloss of his relatives, the von Kessens, where the fox that lives in the attic cries out unnervingly in the night, and where his visit coincides with the Munich putsch of November 1923.

Put baldly like that, The Fox in the Attic sounds like a historical novel of a fairly straightforward kind, but in fact it is anything but. Hughes did indeed go to extraordinary lengths to get the historical details right, blending actual people – including, in a memorable characterisation, Adolf Hitler – and events seamlessly together with invented ones. But the result is a series of interlocking vignettes rather than anything like a linear narrative, in which characters come and go, sometimes attracting our sympathy and attention and interest, only to drift out of the frame, never to return, or else to pop up again many pages later, when they have been forgotten by all but the most alert reader.

The tone of the novel’s narration varies wildly, from portentously philosophical (“each knows his own I-ness”), to lyrically violent (“blood, running in its fine gold, running down till it crimsoned the snow”), to absurdist (“Aneurin was a coasting-smack skipper whose ships always sank and who had now set up as a dentist”), to arch (“the dog’s name I forget”). Yet the overall effect is both precise and panoramic, painting a picture of a world on its way to an unhappy ending, driven there by the “diseased” (Hitler and his cohorts) and the deluded (young Nazis trapped by an idea), unconsciously abetted by the idealistic and the naive. A successor volume, The Wooden Shepherdess, which takes the action to the brink of the second world war, appeared twelve years later, in 1973, but Hughes did not live to continue the projected sequence to its conclusion.

Yet even without the successor volumes, actual or planned, The Fox in the Attic stands impressively on its own as a despairing and humorous chronicle of how adults behaving as children (Augustine remains a kind of perpetual adolescent throughout both volumes), combined with the dominating role of chance in our lives, will lead, more often than not, to tears before bedtime. We see Augustine fall self-absorbedly in love with his German cousin Mitzi without ever registering that her mind is on other things. Despite his determination to declare his love, circumstances conspire against him and he keeps on missing the opportunity to speak, until it is too late. Which is, the novel suggests, probably just as well. These youthful or youth-like impulses can have unforeseen and unwelcome consequences. In a version of the butterfly effect, an impulsive action – a chat with a girl by a swimming-pool, for example – can turn out to be very consequential indeed. •