My son and I share morning coffee regularly, though now we’re isolated in our separate houses we rely on Facetime. Recently, when our talk turned to the cultural amnesia about the influenza pandemic of a century ago — a popular topic at the moment — he said, “Did you know Joycey died of complications from the Spanish flu?”

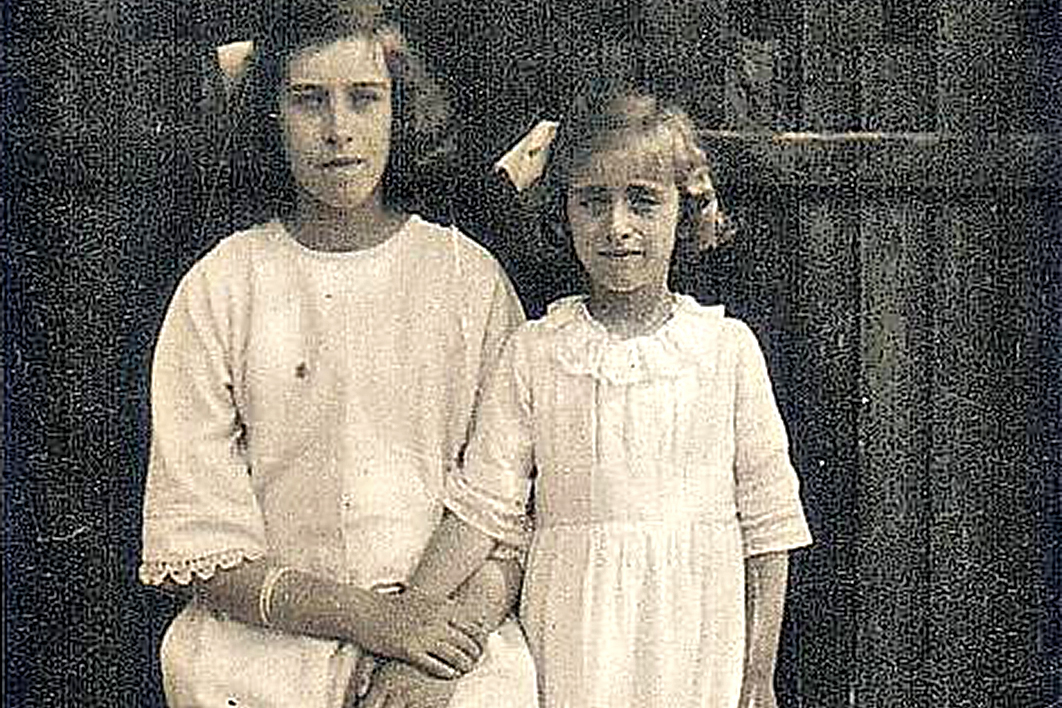

A librarian and historian, Matt was the family history sleuth for my recent collection of memoir essays, and his grasp of our family’s story is much more detailed than mine. I was aware that my mother’s young sister had died as a child but not that she had been struck down at the age of three by the devastating flu that killed at least twenty-five million people, and possibly as many as one hundred million, just after the first world war. My middle name is Joyce, after the aunt I never knew.

Going back through the transcripts of the tapes Matt recorded with his grandmother in the 1990s, I found a comment she had made about her childhood in Watford, near London: “After the war we had a terrible flu epidemic and we all got it, but with Joycey it turned to pneumonia and she never really recovered from it.” The delicate little girl started school but had to give up through illness; she was then nursed at home by her mother until she succumbed to heart failure in 1924, just after her eighth birthday.

The influence of chance on the trajectory of our lives has always fascinated me — how planned paths swerve as a result of an unexpected personal event, or how wars, or indeed pandemics, turn those plans upside down. Thirteen when her sister died, my mother was attending a secondary school that provided early teacher training and was planning to complete the qualification at a college in London. She knew the direction her life was to take. Or so she thought. In fact, having immersed myself in our family archive, delved into Trove and consulted with Matt, I have come to see that the effects of my young aunt’s death from Spanish flu rippled so widely that my very existence can be traced back to it.

My mother, Rose Wythe, lived with her parents and little sister in a comfortable rented house in Watford, its front covered in a Virginia creeper that became “just one big splash of red” in autumn. My grandfather ferried around travellers by horse and trap as a coachman for Kinghams, a large grocery store that smoked its own bacon and hams. My grandmother was the homemaker. My mother loved her school life and the company of her girlfriends there. She was a born teacher, and I feel sure she would have helped Joycey with lessons when her sister was well enough. (She taught me to read at three before being called back to teaching after the second world war.)

Joyce Wythe was buried at Watford cemetery on 23 June 1924, and her grave is watched over by a stone child angel. After the funeral, the house with the Virginia creeper fell silent. Like her father, my mother continued to come home for lunch, but “sometimes there was lunch ready and sometimes there wasn’t. It was a very sad time.”

My mother’s two older brothers had found it hard to enter the workforce after the war ended in 1918. “Lewis was apprenticed to engineering and after the war the soldiers who did come home got their old jobs back,” my mother told Matt. “So that was the end of his apprenticeship. And it was very hard to get anything else. Wilfred was younger — he was very clever artistically and he really wanted to be an architect, but that was wiped on the head too.”

Seeking more opportunities, the two young men had set off to Australia in the first wave of postwar emigration. After Joycey died, Lewis implored his parents to join him and Wilfred and, in their unhappy state, my grandparents eventually agreed to set sail for the other side of the world. My grandmother seems to have regretted the decision for the rest of her life; and my mother, of course, was devastated. “I suppose these days,” she told Matt, “I would have stood out and said I was going to stay behind, even if I got a job to help me. But you did what your parents said then.” At fifteen, she really had no choice.

Before the family set sail in early 1926, my mother spent as much time as she could with her friends, staying the last night at the home of her best friend, Doris. She made sure that two small autograph books I hold in my hands today were packed in her trunk as precious mementos of the life she was to leave behind. They consist mostly of sentimental verses about friendship or extracts from poems by Tennyson, Kipling and others, all written in carefully formed cursive script and signed by friends or teachers.

Interspersed are pen and ink drawings and watercolours, including drawings by one of my mother’s cousins, a teenage boy at the time, from Aldeburgh in Suffolk. Dated August 1921, they show that he was fascinated by the machines of war — airships, warplanes and steamships — that he had grown up with. Watercolours of flowers by my mother’s friend Doris stand out for their artistry. The two women were still corresponding seventy years later.

A farewell watercolour by Rose’s friend Doris.

The voyage on the P&O steamer SS Barrabool, bound for Adelaide, Melbourne and Sydney with more than 1000 emigrants on board, was more eventful than any of the passengers could have imagined. My grandmother, a “bad traveller,” was seasick for most of the journey and confined to her cabin. So she wasn’t among the passengers who stood on deck for hours — in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, en route to Cape Town — watching a lifeboat ferrying people from a burning cargo ship, the Parapoa, which carried sixty-nine crew and five passengers. All were rescued safely, including six stowaways and a pedigreed fox terrier. An open crate of pigeons remained on the ship, left to fly away if they could. Those rescued were disembarked at Cape Town, and that was where, according to my mother’s memory, passengers with smallpox were unwittingly taken on board. Five people would die over the next weeks.

Newspaper accounts of the outbreak on the Barrabool vary, but the one in the Adelaide Advertiser of 12 April 1926, which describes the scene after the ship docked at Semaphore, resonates uncannily with accounts of Covid-19 on cruise ships docking in Australian waters in 2020:

The vessel was boarded by Drs. C. Wiburd and P.T.S. Cherry, who were handed the primary health report, which stated that no sickness had occurred on board, with the exception of a series of cases of measles among children. However, as Dr. Wiburd was leaving the ship’s hospital, he noticed two male passengers on the deck with a rash on their faces which indicated smallpox. One of the men seemed to have had only a mild attack of the disease. Both sufferers, who had been in a febrile condition, were mingling among other passengers on the deck… Drs. Cherry and Wiburd, in the course of the examination of the other passengers, found another man whose face, hands and feet were covered with the scars of smallpox. He had taken ill shortly after the vessel had sailed from Las Palmas, and after being detained in the ship’s hospital for some days, was discharged.

The passengers bound for Adelaide and those who were ill were taken to the quarantine station on Torrens Island, where they were disinfected, vaccinated and placed in quarantine. The remaining passengers heading to Melbourne and Sydney were vaccinated on board before the ship resumed its delayed journey. From Port Melbourne approximately 300 were taken to the Port Nepean Quarantine Station, perched on the rugged coastline at the tip of the Mornington Peninsula. Some 600 passengers then continued on to Sydney.

The Melbourne Argus announces the Barrabool’s quarantine.

Those sixteen days’ quarantine at Portsea were my family’s introduction to their new country. My mother remembered the seaside town as a beautiful place, although the station itself was very plain and the inmates slept in barracks. She would have seen the administration building, erected in 1916, with its handsome facade, but that is not where the internees were housed. In her recollection, “ships came back, I don’t know how many times, bringing the dead — the Sydney people. It was an awful beginning.”

Although that part of her story can’t be verified, an account in the Melbourne Age of 30 April 1926, two days after most of those quarantined were released, does support some of her memories:

The first case of small-pox was recorded at Las Palmas, and during the continuation of the voyage a number of the vessel’s passengers contracted the disease. During the latter part of the voyage five deaths were recorded. Two of the crew and one passenger contracted pneumonia with fatal consequences. A girl of thirteen years also died of the malady. The last death was recorded on Monday, when a child two days old died.

The quarantine station at Portsea had opened in 1852, making it one of the first in Australia. The oldest buildings on the site, which continued operating until 1980, date back to that period. It was the scene of part of the little-known history of Spanish flu in Australia, after servicemen suffering from the disease started pouring back into the country from the war in Europe in 1919. Twelve emergency timber huts were hastily erected, each holding thirty-two men, which suggests the victims numbered in their hundreds. In total, an estimated thirteen to fifteen thousand people died in Australia during the pandemic.

Because my grandfather reacted badly to the vaccination and had a severely swollen arm, my family was kept at Portsea for a week longer than most of the new settlers. As my mother recalled, “I had a pretty bad arm, but my father’s was terrible… And Mother, who had been so sick on the ship, was immune to the vaccination — it didn’t have any side-effects at all.” With Wilfred having already moved to Sydney, the travellers eventually met up with Lewis in Melbourne. Instead of finding accommodation for them in the city, he took them twenty miles away to Werribee, then a small country town. There, my grandfather found work as a stableman and labourer at the State Research Farm, where he would spend the rest of his working years.

My grandmother hated Werribee and my mother resented Lewis for the rest of her life. “He was always doing the wrong thing, that brother,” she told Matt. “I don’t owe him anything. He was such a queer bird. Funny how people can be so different in a family.” It seems that the feeling was mutual; as she remarked dryly to Matt, “He was the one who told me that if I ever knitted anything for him he wouldn’t wear it anyway. So I didn’t knit anything for him.”

In spite of these inauspicious beginnings, Werribee was to play an important role in our family history. My mother became a relief teacher a few years after she arrived, leaving the little town for extended periods to work at single-teacher schools around the state. But Werribee was where she met her future husband, who was working in his father’s cafe and playing piano in a local band. They married in Scots Church in Melbourne in 1935 and, using my father’s skills as a pastry chef, opened a cake shop in the eastern suburb of Glen Iris.

Their suburban life was short-lived. When the second world war broke out in 1939 — the second world conflict they were to live through — my father joined the airforce and my mother followed him from posting to posting with their baby son. I arrived towards the end of the war and, after my mother was recalled to teaching during the early postwar boom, I started school before I turned five.

In the light of my family research, I pondered again the question of why the Spanish flu has left such a small footprint on our collective memory and came up with some possible answers. The pandemic came on the heels of a war that ravaged the world, of course, and has thus remained hidden in its shadow. More than that, my parents’ generation lived through a century that encompassed not one but two world wars. As well as causing death and disaster, wars can create the heroes and narratives that define a nation; pandemics offer no enemy but the disease itself, and are thus harder to memorialise. People simply wish to forget them.

In a collection of essays on the history of quarantine, Anne Clarke, Ursula K. Frederick and Peter Hobbins remark on the inconsistency between historical records and stone inscriptions. They speculate that the paucity of inscriptions mentioning disease at quarantine station sites could reflect “a strategic amnesia — a way of moving forward and beyond the spectre of death.” Mentioning the SS Barrabool as an exception, they observe that the vessel is virtually missing from the historical archive (and the varying accounts I did unearth are wildly inconsistent) and yet its smallpox cases are mentioned on a number of rock inscriptions around the quarantine station at Sydney’s North Head, which was the ship’s final destination on that fateful voyage. Perhaps the discrepancy can be explained by the fact that forty of the passengers on board were stonemasons who were specially recruited in England to craft the stone foundations of the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

Uncovering small stories like my family’s can shed light on the larger narratives of wars and pandemics. Writing this, in the midst of the coronavirus, a century after my young aunt was stricken by the Spanish flu, I find a certain ironic symmetry in our stories. Joycey was a child during a pandemic that struck children in larger numbers than any other age group. This time it is the older generation that is most vulnerable and I am completely housebound, except for a daily walk with the dog, for the foreseeable future. I am one of the privileged, though, as I share my comfortable home with my partner, with my books, archives and the internet at my fingertips, and with frequent virtual access to family and friends. •

My thanks to Matthew Stephens for his assistance in the research for this essay.