Part of our collection of articles on Australian history’s missing women, in collaboration with the Australian Dictionary of Biography

In the early hours of 22 November 1941, a constable on patrol duty in Sydney’s eastern suburbs found an unresponsive elderly woman in a park shelter. She was wearing sandshoes, a felt hat and several old military overcoats; two sugar bags contained her only possessions. The constable recognised her as “Bondi Mary” and called an ambulance, but she had died in her sleep. Police arranged for her to be buried among other unknown homeless people in an unmarked communal grave in the Church of England paupers’ section of Rookwood cemetery.

Homeless she may have been; unknown she was not. She even had a racehorse named after her. After her death was reported widely in the newspapers, a Leichhardt businessman, John (Jack) Packer, soon claimed the body as his mother’s. She was buried on 25 November 1941 in Rookwood’s Roman Catholic section, survived by her son, his wife and their children. As the Cairns Post commented, “Although thousands of people knew her, she knew no one — a lonely, lost figure among Sydney’s huge population.” Few knew the woman she used to be: Mrs Helen Packer and, before that, Miss Bridget Ellen Peterson.

Born in Muswellbrook, New South Wales in 1870, Bridget Peterson was the second of fourteen children, and among the six surviving daughters, of Swedish-born David Peterson and Irish-born Mary Peterson (nee Ryan). David Peterson’s work on the NSW railways caused the family to move often around the northern region of the state. At one time, Bridget’s mother was also employed by the railways as a gatekeeper. The family were devout Catholics.

Bridget became an unmarried mother in 1904 when her son John Packer was born. She was known as “Mrs Packer,” a smartly dressed, prosperous “widow.” She too moved around: working for Farmer and Co. and David Jones in Sydney; supervising dressmakers at Carse and Co. in Charters Towers, inland from Townsville, by early 1907; and, soon after that, advertising her dressmaking skills as “Madame Pacquer” in Brisbane and then back in Sydney. In May 1911 she shifted to Condobolin in New South Wales and set up a dressmaking business.

By 1913, Madame Pacquer had workrooms and a home on the second floor of a building owned by Sydney Ferries Proprietary Limited near the Milson’s Point wharf. She advertised as a “French Modiste,” and her skill in cutting clothes “on Parisian lines” attracted many of Sydney’s best-dressed women to her costumière rooms.

When rooms on the ground floor of her building were being turned into a dentist’s surgery in October 1913, she complained to her landlord’s agent about the smell of gas. Workmen checked but found nothing. The next afternoon, however, a violent explosion hurled her son, Jack, through a window and onto the ground thirty feet away. He was hospitalised, unconscious, but recovered.

Madame Pacquer was not physically hurt but received a severe shock. This, “combined with anxiety for her little boy… prostrated her,” according to the newspapers. She managed to continue her business in Sydney for a short time after the explosion, and in 1914 was advertising for assistants. But she had a breakdown at some point over the next two years and took to living alone on the streets. She was eventually incarcerated in prisons, hospitals and mental institutions.

Madame Pacquer was first arrested in January 1918 and sent to Long Bay Reformatory. After a week they decided she was “mad” rather than bad and sent her to the observation ward at the Lunatic Reception House in Darlinghurst. She was then admitted voluntarily to Gladesville mental hospital under the name “Ellen Packer,” from where she was discharged three months later.

From Gladesville she went to Condobolin hospital, where she contacted her son, then aged fifteen. Released from hospital, she was found “wandering at large” at Condobolin. She was taken into charge by the police and sent to Parramatta mental hospital via the Reception House, this time as a non-voluntary patient.

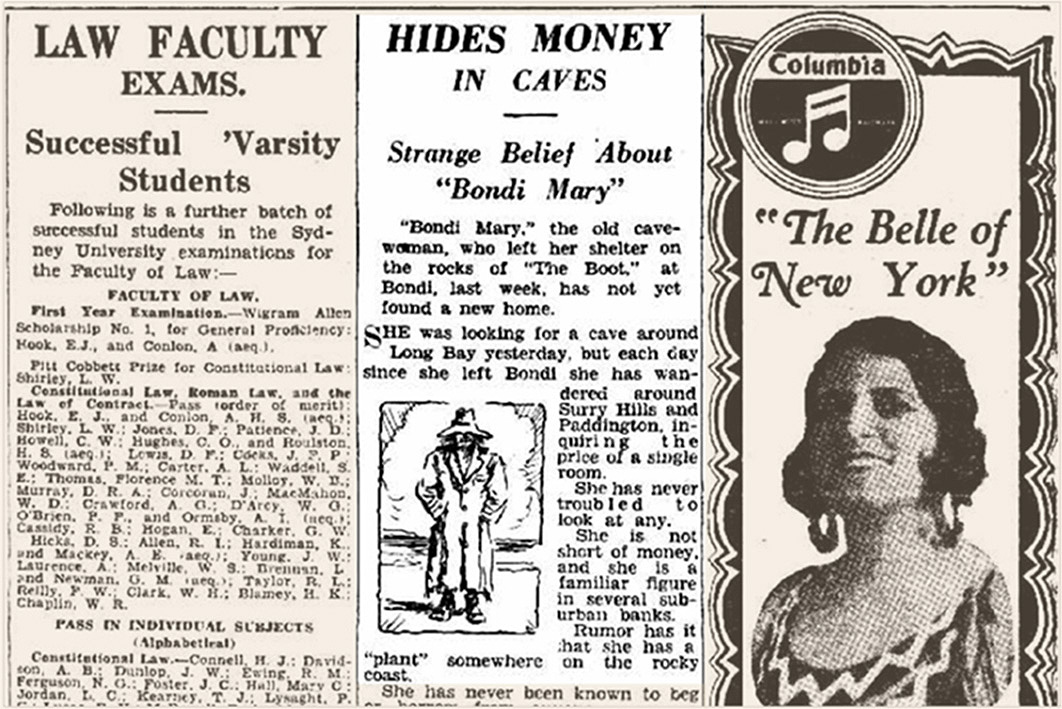

At some stage she was left “to wander.” Her son later claimed that she spurned her sisters, as well as the attempts he and his wife made to induce her to live with them. By the late 1920s, “Bondi Mary” had become a well-known figure, combing the beach during the day for treasure, which she stored in her sugar bags, and sheltering in a cave during the cold weather and in summerhouses on hot nights. Once a week she walked from Bondi into the city. The Daily Pictorial published a drawing of her, “the old cave woman,” with stories of her hiding money in the caves. During the Great Depression, she joined all the other battlers gathered outside the Bondi Beach Post Office on dole day, while the local police crossed off their names and gave them chits to obtain food from local shops.

It was possibly an intended kindness when she was sent to jail for three months for vagrancy in the winter of 1934. Constable Newman told the court that he found her, the picture of poverty, in Edward Street near Moore Street: “It was raining and she was sitting in the gutter drinking methylated spirit. She had only a penny in her possession.” Mr Macdonald SM sentenced her to three months’ imprisonment, remarking “that it would take her over the winter months.”

Gradually her health deteriorated. She was obviously malnourished, according to police, and suffering from “senile decay.” There was no inquest into her death; the cause was given simply as “chronic alcoholism and kidney disease.” While mental illness is not the primary cause of homelessness, now or in the past, it lay behind Bondi Mary’s life on Sydney’s streets.

Ellen Peterson was only one of thousands of Australian vagrants in the first part of the twentieth century, but she is distinguished by the fact that we know this much of her story. •