In London’s bustling East End a circular garden of surprising calm sits on a mound at the centre of the giant Arnold Circus roundabout. The still hub of a wheel, its radiating spokes are formed by broad avenues lined with four-storey terraces built in the Art and Crafts style: solid red brickwork shot through with decorative bands of yellow; ornate porticos sheltering entrances with solid timber doors; generous, white-painted windows hinting at high-ceilinged rooms within. With its mature plane trees and hexagonal bandstand, the garden and its surrounding architecture have a stately feel.

This is the Boundary Estate, a public housing scheme that has provided quality homes to working-class Londoners since 1900. It was Britain’s first council housing project and one of the earliest examples anywhere of public investment in affordable homes.

The rise of the estate’s circular garden is reminiscent of an Anglo-Saxon burial mound — and it is a burial place of sorts, interring the rubble of Old Nichol, a notorious East End slum demolished in the 1890s. Described by the Illustrated London News as a “painful and monotonous round of vice, filth and poverty,” Old Nichol was a place of disease and deprivation. Thousands of families crowded into dwellings of just one or two rooms, the walls held together by cheap “billy-sweet,” a mortar that never dried out. Babies born in the slum had a one-in-four chance of dying before their first birthday.

For about eighty years after the Boundary Estate opened, almost all public housing in Britain was “council housing,” built and operated by local authorities. In Australia, state governments took the lead. In both cases public investment dried up in the closing decades of the twentieth century, ushering in a period of decline in the quantity and quality — and the reputation — of public housing.

In both places, housing construction and management increasingly shifted away from governments, local or state, to not-for-profit housing providers, although this process is further advanced in Britain than Australia. What was once known as council or public housing is now generally covered by the broader banner of “social housing.”

My guide through the Boundary Estate is social historian John Boughton, and I’ve drawn liberally on the opening chapter of his book Municipal Dreams, a chronicle of the rise and fall of council housing in Britain, in describing its history. The book grew out of his blog of the same name, launched a decade ago as a retirement project after he left his job teaching history to senior high school students.

“It was completely normal”: the Boundary Estate today. Peter Mares

For Boughton — whose long-term Labour Party membership included what he calls a brief, unremarkable stint as an elected local government official — the neglected subject of council housing chimed with existing political and academic interests. It deserved greater attention, he thought, but he never expected his blog to prove so popular.

“It just took off,” he says. “It caught a moment.” Boughton thinks the contemporary housing crisis has spurred interest in his writing by exposing the limitations of a neoliberal reliance on private capital and free markets to address complex social challenges. “People are starting to look with more sympathetic eyes on the role of the state, in housing in particular.”

Perhaps, too, the blog hit a chord with a generation shaped by council housing. Many of Boughton’s relatives lived on council estates, as did friends and acquaintances. “It was completely normal,” he says. One in three Britons lived in a council home in 1981, and it was often the best housing they had ever experienced.

Today, though, council housing suffers from an image problem almost as bad as Old Nichol’s in the nineteenth century.

I met Boughton soon after the final episode of the hugely popular Happy Valley screened on the BBC. As in many British crime series, part of the action took place on a council estate — in this case in Yorkshire, where a troubled woman was exploited by an unscrupulous criminal duo.

The image of crime- and poverty-ridden housing estates, reinforced time after time in fictional series and news coverage, has stuck. “The tendency to associate council housing with criminality has exaggerated and denigrated the experiences of millions of people currently and in the past,” says Boughton. “That is not to deny problems and missteps along the way. But it is a negative stereotype, and it is self-reinforcing.”

Where problems do arise on particular estates at particular times, they are always shaped by larger forces, he says, and especially the profound effect of demographics.

He cites the Pepys Estate, just south of the Thames in the Borough of Lewisham, which was very popular when it opened in 1973. Built on the site of a former naval dockyard and accommodating 5000 people in 1500 homes, it was one of the Greater London Council’s largest and most prestigious projects. Design innovations included basement garages to separate pedestrians from cars and elevated walkways between blocks to encourage neighbourly interaction. In TV dramas, these same locations are now likely to feature as hangouts for loitering gangs and escape routes for villains.

High-rise flats have become particularly reviled for facilitating antisocial behaviour, as if the fault resides in the very fabric of the buildings. Boughton insists the architecture isn’t to blame. “A great variety of estates have suffered problems,” he says. “Low-rise estates too, not just tower blocks.”

The roots of such ills lie elsewhere. In the decade from 1978, Lewisham lost 10,000 jobs and unemployment trebled. By the mid 1980s more than half the borough’s residents aged sixteen to twenty-nine were jobless. The Pepys Estate was hit hard, and an alternative economy sprang up based on drugs and crime. Racism was rife. Rather than fighting to get into a flat, people were begging to be transferred out.

Boughton tells a similar story abou the Park Hill Estate, a 996-flat scheme that replaced some of the worst slums in Sheffield. Completed in 1961, it also had “streets in the sky” — elevated walkways wide enough for children to play on, which enabled neighbours to chat without the noise and disruption of passing traffic. It had shops, pubs, schools, clinics, community centres and, in the words of one resident, other unaccustomed luxuries: “Three bedrooms, hot water, always warm. And the view. It’s lovely, especially at night when it’s all lit up.”

By the early 1980s, though, Park Hill was another towering symbol of council housing failure, its celebrated brutalist architecture blamed for criminality and vandalism. What rarely gets mentioned is that in the intervening decade Sheffield had lost a massive 40,000 jobs.

“Council housing does not exist in a vacuum. It exists in a social and economic context,” says Boughton. “What is happening to these communities is the product of policy and political choices.”

Attitudes towards council housing also changed as Britain became more affluent. “Into the 1960s, it was the best housing most working-class people could aspire to,” says Boughton. “But as owner-occupation became more widespread, council housing was seen as less desirable for sure. There was a psychological shift.”

As the economy declined in the wake of the oil shock and stagflation in the 1970s, public spending fell too. Repair and maintenance were neglected. Labour, which had once believed council housing should meet “general needs,” moved closer to the Conservatives’ view that it was better seen as a welfare safety net reserved for the vulnerable.

At one level, the shift (which was mirrored in Australia) makes sense: the fairest way to manage limited public resources is to prioritise the neediest. Over time, though, social housing was transformed into housing of last resort — an ambulance service that picks people up from the bottom of the cliff rather than a fence preventing anyone from falling.

Forty years later, social housing in both Britain and Australia accommodates an increasingly narrow stratum of society — the very poorest and those experiencing the most layers of disadvantage. This “residualisation” makes it easier, in turn, to stigmatise residents as “troubled” and point to “failed estates” as evidence that public investment in decent housing is a fundamentally flawed ideal.

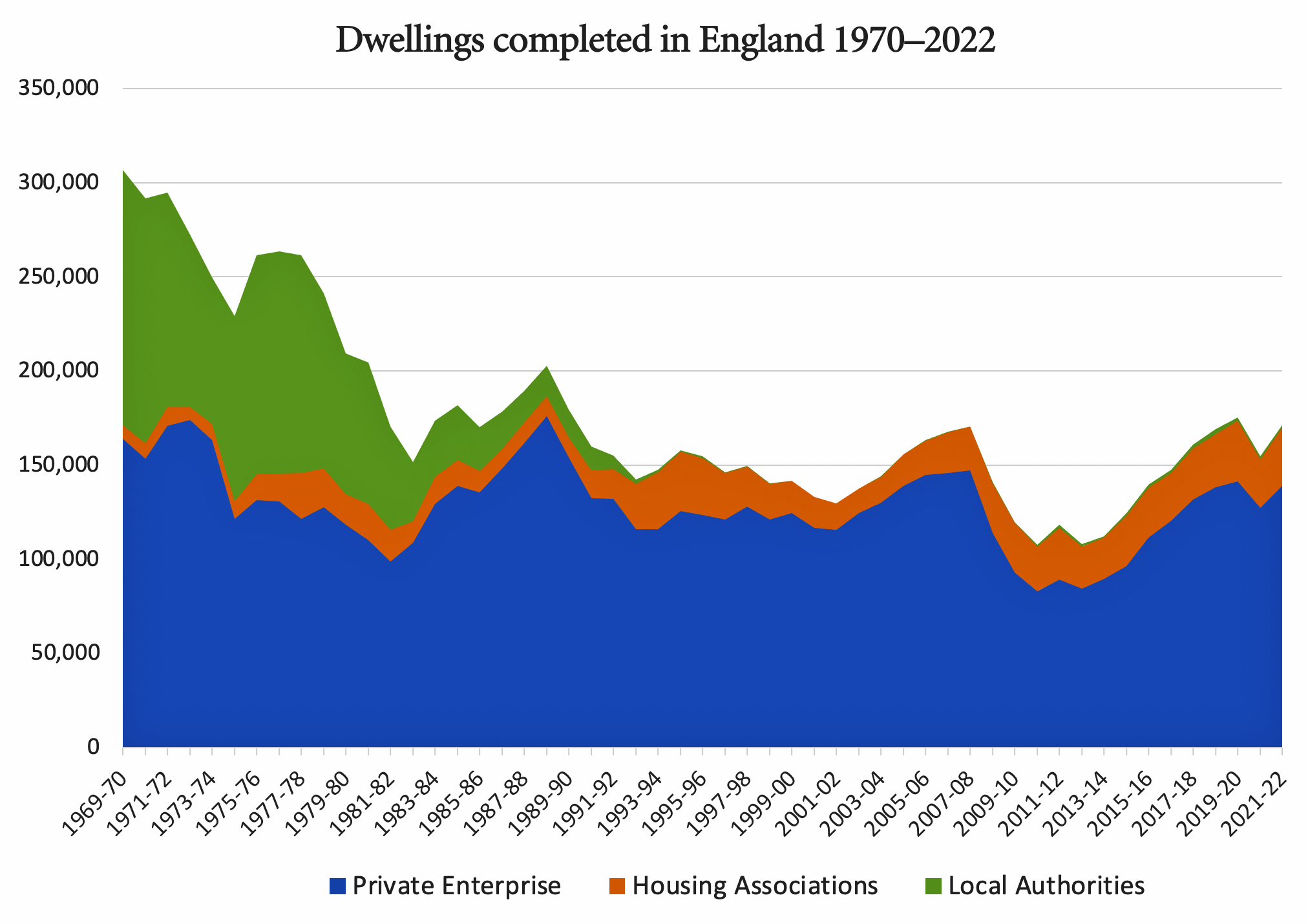

Residualisation was compounded in 1980s Britain by the hammer blow of Thatcherism. The national government cut investment in council housing and stopped new construction in its tracks. In the year Conservative prime minister Margaret Thatcher took office, building commenced on nearly 80,000 new council homes in England and Wales. Within a decade, annual new starts had fallen to just 400. But when councils stopped building in England — the green band on the chart below — the private sector failed to pick up the slack. The overall supply of new housing dropped precipitously and has never recovered.

Source: Live table 213, Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities and Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government

Determined to convert Britain into a nation of homeowners, Thatcher also introduced the right-to-buy scheme. By the time the Conservatives lost office in 1997, one-in-four council homes had been sold, with prices discounted by between a third and a half of market value (up to a ceiling of £50,000). It amounted to a massive, highly subsidised transfer of public assets into private hands, and most of the receipts went straight to Treasury to retire debt.

Tenants with means were supported to become owner-occupiers; those without got less assistance than before as public investment in council housing dried up. “Typically, the best, most desirable homes got sold and the less desirable units got left,” says Boughton. “It was another form of residualisation.”

For many, this brought windfall profits. Boughton gives the example of a security guard living on a council estate in Camden who bought his flat for £39,000 under the scheme. It was valued at £70,000 at the time. Three decades later, his home was worth £600,000. Not surprisingly, he thought the scheme was “perfect.”

“The irony is that generally the first generation of former tenants who became owner-occupiers then sold off those homes,” Boughton says. Forty per cent of homes bought by their tenants are now back on the private rental market, though in poorer condition and with higher rents than the council houses next door.

“If you walk onto a suburban council estate, the well-maintained and modernised houses are council owned, while those sold under the right-to-buy scheme are least well maintained and equipped,” says Boughton. “The market does not do a very good job.”

About 40 per cent of the homes in the Boundary Estate are now in private hands, and those that are rented out are seen as desirable properties. At the “guide price” of £450 per week, a one-bedroom flat would eat up the entire pay packet of a full-time worker earning the London Living Wage.

The rest of the estate’s residents remain tenants of Tower Hamlets, the local authority. In 2006, the tenants vetoed a plan to transfer the estate from the council to the not-for-profit Southern Housing Group, even though the housing association had promised to redecorate the flats and install new kitchens, bathrooms and boilers.

In hundreds of other estates, tenants have voted to switch from the local authority to a housing association. Back in 2001, two-thirds of all social housing in England was owned and operated by local governments and one-third by registered housing providers. Today, those figures are almost reversed, and fewer than four in ten homes remain in council hands.

For the Conservatives, the shift from local authorities to housing providers was — like the right-to-buy scheme — ideological. Boughton says the Tory government genuinely believed that council housing was “the state at its worst, bureaucratic, distant and inefficient.”

While acknowledging that an era of austerity made it difficult for councils to maintain the quality of housing, he says there was some justification for the Thatcherite critique. “It varied from council to council, but some took their eyes off the ball, neglecting maintenance and repair,” he says. “Ongoing expenses were not always budgeted for.” The results weren’t all bad, he adds: local governments responded by decentralising decision-making and devolving management.

The shift to not-for-profit housing associations continued after Labour took government in 1997. Smaller and locally based, housing associations were seen as more agile than councils, more attentive to tenants’ needs and better aligned with Tony Blair’s “Third Way.”

These arguments are familiar in Australia, where the not-for-profit, or “community,” sector is also growing. The Community Housing Industry Association’s chief executive, Wendy Hayhurst, recently urged the Albanese government to direct all the proceeds from its $10 billion Housing Australia Future Fund to her sector rather than do the “easy thing” and divvy the money up among community, state and private providers.

Hayhurst argued that community housing scores better on ratings of quality and resident satisfaction, a claim supported by the Productivity Commission’s most recent Report on Government Services. With its charitable status, the community sector is exempt from GST, land tax and stamp duty, which Hayhurst says enables it to build more houses for any given amount of money than state governments or businesses can.

Duncan Maclennan, a housing expert at the University of Glasgow with extensive experience in Australia, argues that not-for-profits provide better management than state authorities and better integration with other services. He says they are more effective at using their housing assets to secure low-cost private capital for additional investment. “There is a strong case to see much stronger policies of transferring public stock to non-profits,” he concludes.

Though not as advanced as in Britain, the shift from state governments to community providers is already under way in Australia. Over the past five years, more than 21,000 homes have been transferred from public sector to registered housing providers, two-thirds of them in New South Wales. Around 70 per cent remain in state hands, but this is down from 85 per cent in 2008.

The trend is clear, yet the British experience gives pause for thought. Or at least the English experience — thanks to devolution, policies differ in Scotland and Wales.

Take the Juniper Crescent estate, for instance, which won architectural awards after it was completed by inner-north London’s Camden Council in 1996. Across the road from the estate, near some once-hip but now-tawdry markets, builders are hammering away at a £1 billion development, Camden Goods Yards. What was once a commercial site is being transformed into a mixed-use neighbourhood with 644 homes, Grade A office space, a supermarket, a rooftop farm and “landscaped open space for the whole community to explore.”

Thanks to inclusionary zoning requirements, the developers are supposed to include some affordable housing as well — as they are in all new housing projects in England. As a planning requirement, an agreement on the quantity and price range is generally negotiated between developers and local governments, though John Boughton says developers sometimes wriggle out of these commitments and, besides, “affordable is a pretty loose term.”

Sound from the construction site at Camden Goods Yard is audible from Juniper Crescent, which is now run by One Housing, one of London’s largest housing associations. Juniper Crescent might need some upgrades, but it is far from past its use-by date. Yet these 120 terrace homes in stylish yellow brick will soon be demolished as part of a redevelopment more in line with the high-end condominiums being built across the way.

The knockdown rebuild plan required the consent of Juniper Crescent residents, but in a 2020 ballot they voted the proposal down. One Housing’s response was to engage “with residents further about the regeneration proposals in order to understand the ballot results more fully.” In other words, keep trying until the residents gave the right answer. After consultations fuelled by glossy brochures, free pizza and live music, residents voting narrowly in favour of demolition.

One Housing has promised that all current residents will be able to return to the redeveloped estate. Residents will have more open space than before, it says, and their new better-quality homes will be just as spacious as their present dwellings. Each household will receive a £7800 “home loss payment” to compensate for years of disruption.

The demolition of an estate built less than thirty years ago reflects the way markets are structured, says Boughton. Little incentive exists to refurbish and upgrade existing council housing. The financial imperative is for developers to demolish and rebuild, tapping in to profits from new homes for sale and private rental. Projects are justified, with some plausibility, because they bring densification.

The soon-to-be-demolished Juniper Crescent estate. Peter Mares

Redeveloping Juniper Crescent will create about three times as many homes as the estate has now, adding much-needed supply to London’s over-taxed housing market. What remains unclear, though, is how many of these additional homes will be truly affordable for low-income tenants. As even its supporters acknowledge, One Housing’s motivation in this partnership with a private developer is as much financial as social: it needs to generate income from commercial projects to fund its broader operations.

For Boughton, this attempts to turn necessity into a virtue. Housing associations cross-subsidise their social mission by building housing for private sale or market rents. A touted benefit is the creation of “mixed communities,” where rich and poor, renters and owner-occupiers, live side by side and share facilities. Boughton welcomes this aim, noting that this is what all council estates originally were. But he adds, wryly, that no one seems to worry about the lack of social mix in middle-class suburbia, let alone in the exclusive neighbourhoods favoured by plutocrats.

Yet Boughton also fears that housing associations increasingly look and behave like property developers. Even when they separate their commercial and social operations in different divisions, they risk letting the for-profit tail wag the housing-association dog.

“I’m not criticising good housing associations with local roots and a strong grasp of social purpose,” says Boughton. “I’ve got plenty of time for those. But now they have consolidated and got bigger, many are suffering from some of the same evils once attributed to councils.”

There is a compelling argument that Australia’s nascent community housing sector must also grow, professionalise, and consolidate into fewer larger organisations if it is to operate efficiently through economies of scale and a deep well of corporate knowledge. Yet in England, signs suggest that some of the biggest housing associations are losing touch with their residents and becoming disconnected from their social purpose.

CEOs now command impressive salaries and privately lobby government to let them charge tenants higher rents. One Housing is accused of leaving some of its elderly tenants without heating or hot water through winter after bungling boiler repair work. Another big provider, L&Q, was recently rapped on the knuckles by the Housing Ombudsman with two severe maladministration findings over its treatment of a tenant with physical and mental vulnerabilities.

In one chilling case, the Peabody Group apologised after one of its tenants was left dead in her flat for more than two years. Neighbours had complained about a foul stench and Peabody had cut off the woman’s gas because of unpaid bills yet failed to check on her welfare.

Anecdotes are not proof of system failure, nor evidence that things would have been better if councils had remained in control. The G15 alliance of London’s biggest housing associations provides homes for around one-in-ten Londoners: in a sector so large things will always go wrong. Yet the potential for social purpose to be eroded remains real, especially when the sector remains starved of public funds.

This is apparent in the types of housing that are now getting built. Rather than “social rent housing” — that is, homes for people on the bottom rungs of the income ladder — housing associations in England are increasingly building other types of “affordable” housing, including properties rented for as much as 80 per cent of the local market rate — which, whether in London, Melbourne or Sydney, is often still very expensive. One “affordable” property currently listed by Australian social venture HomeGround Real Estate is a two-bedroom apartment at $1100 per week.

Affordable housing is often portrayed as “key worker” housing. It is intended to enable teachers, nurses, childcare workers, police officers, hospitality staff and sales assistants to live closer to their jobs. These are tenants that private developers would welcome in joint ventures like the Juniper Crescent rebuild — if they can afford it. Social renters, who often rely on government benefits, don’t fit so comfortably in marketing brochures.

Boughton warns that social rent housing will always come second under a cross-subsidy model. “You will never have the amount of social rent housing that is truly affordable being built. It will always be neglected.”

The statistics seem to bear him out. In 2021–22, about 60,000 homes were added to England’s “affordable housing” stock, almost half of them resulting from inclusionary zoning agreements. But only about 13 per cent of the total — or 7500 dwellings — were designated as social rent. That proportion has been steady for about ten years.

In the previous decade, though, social rent housing made up 50 to 60 per cent of new dwellings. In the decade before that, it was 70 to 80 per cent. When sales and demolitions are taken into account, Shelter England calculates that England has lost more than 165,000 social rent homes in the past decade.

Today, London south of the Thames is more affluent and desirable than it was in the 1970s, and the Pepys Estate has been rehabilitated. “The Pepys Estate was famous, then it was infamous, now it just looks and feels like a pretty decent place to live,” writes Boughton in a blog post.

After Lewisham Council transferred the estate to a housing association, it underwent an award-winning redevelopment during which many original buildings were demolished, especially those closest to the river. In what Boughton describes as “pure and unabashed gentrification,” a twenty-four-storey tower block with 144 flats was sold to Berkeley Homes, which stacked an additional five floors with fourteen penthouses on top and flogged off all the apartments at a premium.

In this case, the tower block design didn’t seem to be an automatic generator of crime and dysfunction, though the tower did get a new entrance to avoid any taint of council estate. As Boughton explains on his blog, this was another example of financial considerations determining social outcomes:

Lewisham Council claimed to have run out of money and it’s true enough that the rules of the game were — and are — designed to curtail the ability of local councils to improve and expand their housing stock. But it suited, too, a gentrifying agenda which sees some London councils only too keen to bring the middle-class and their money into their boroughs.

For those with municipal dreams, providing decent housing that caters for all, including people with the fewest resources, has been a challenge right from the start. When Old Nichol was cleared to make room for the Boundary Estate, only eleven residents from the original slum made it into the new apartments. Housing generally went to the members of the artisan working class, skilled tradespeople with reliable incomes who today might be described as “key workers.”

Whether housing is built and run by councils, by state governments, by not-for-profits or indeed by private enterprise, it will only provide decent homes for all, including the most disadvantaged, if it receives substantial and ongoing public investment. One persistent hope in Australia is that superannuation funds will invest in social housing, but as the Community Housing Industry Association’s Wendy Hayhurst and Matt Linden from Industry Super Australia write, this can only work if there is consistent and long-term government subsidy to generate the returns institutional investors require for their members.

As Australian housing policy expert Vivienne Milligan warns, only governments can fill the gap between the rent poor tenants can afford to pay and what it costs to build, run and maintain their homes, let alone generate a profit. A reliance on inclusionary zoning and cross-subsidies from commercial projects is just not going to cut it.

Boughton has an abiding sympathy for old-style council housing but is far from dogmatic about whether it should be in local government hands or run by not-for-profits. “Anything that provides genuinely affordable housing and looks after buildings and tenants is welcome,” he says. “A significant share of the population will never own their own home, and housing association, or local authority housing, should and can cater for a broader range of the population.”

But, he adds, “I do advocate for local authority house building as a cost-effective and affordable means of providing housing, as demonstrated from the 1890s to the 1970s.” Between 1945 and 1979, councils built an average of 126,000 dwellings each year. “Local authorities were able to borrow from the national government and use rents to repay loans. They had the resources, organisation, financial clout, and political will to build at scale. That’s what we’ve lost.”

Local authorities also build to a higher standard than commercial developers, says Boughton. “No one is looking to Barratt for best practice,” he says, referring to one of Britain’s biggest mass home builders. “But the very best council housing is something to aspire to.”

Boughton’s new book, A History of Council Housing in 100 Estates, concludes with a profile of Goldsmith Street, a Norwich City Council project of around a hundred highly energy-efficient homes. Awarding it the 2019 Stirling Prize, judges from the Royal Institute of British Architects called the project “a modest masterpiece.”

“Not everywhere can be like that,” says Boughton, “but it’s not a pipe dream to think that local authorities can play that role.” •

Funding for this article from the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund is gratefully acknowledged.