Sydney and Melbourne, Australia’s two largest cities, are struggling to maintain their status as the economic powerhouses of the nation. For decades now, these two cities have attracted the majority of Australia’s new migrants, international students and speculative property investment. Liveable and diverse, they are are the places where increased density has become a necessary by-product of progress; where tall buildings, like quarterly profits, are a function of growth that must never cease.

Except for now. This quarter, there’s little growth to be seen, and the tall buildings are relatively empty. Many office buildings in the CBD report occupancy rates below 30 per cent. In Sydney, where much of life has opened up, it’s the suburbs that are bustling. The relative emptiness of the CBD means money is staying away, no longer coursing freely through shops, cafes and restaurants. Busy intermediaries weave through the suburbs on bikes or in vans, delivering goods and food to shoppers who remain closeted away with their devices.

If the relative emptiness of the central city feels like a shock, we’d do well to remember how relatively novel is the particular, pre-pandemic form of the city we’re familiar with. Skyscrapers stacked tight in the centres, with radial train networks transporting commuters in and out of dormitory suburbs, represent distinct configurations of home and work, domesticity and commerce, that might be slipping. Has the “age of dispersion” arrived? Will investors continue to capitalise on the empty air above certain streets, building more towers for more offices, extending the decades-run of speculative property investment centred around CBD locations — or will another urban form take root?

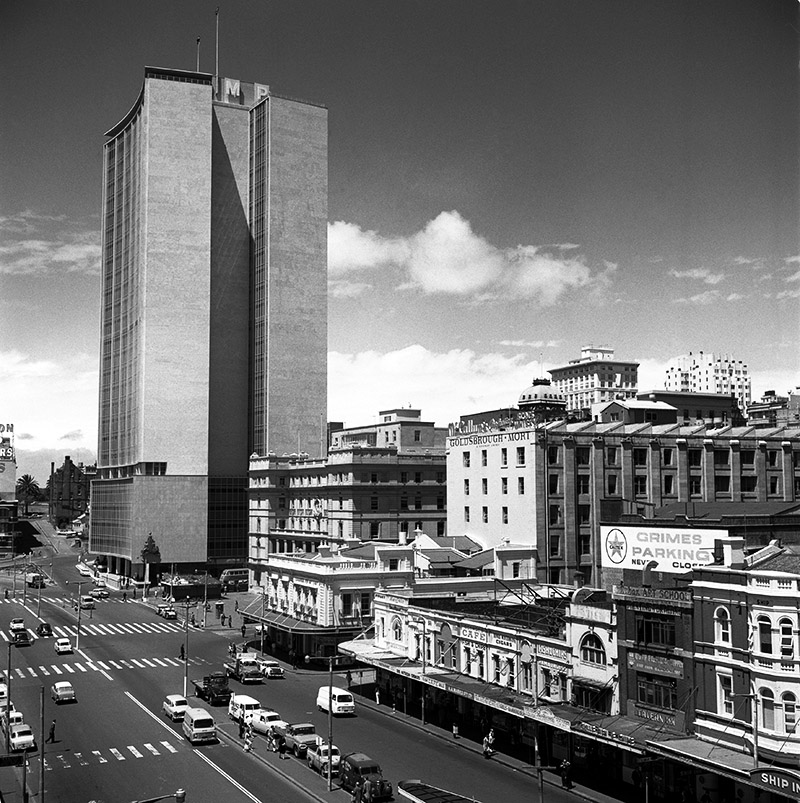

As it happens, the tall building wasn’t welcome in Australia’s biggest cities for many years. The City of Sydney’s first modern skyscraper, the AMP building on Alfred Street in Circular Quay, was only completed in 1961, well after the first tall buildings were emerging across American cities. When it arrived at its harbourside address, it was a gargantuan structure, towering twenty-two storeys over neighbouring buildings like some kind of alien life-form. It shattered the human scale of the street, delineating new sightlines for speculative growth.

The building was only possible because of the lifting, in 1957, of the Height of Buildings Act 1912, which had been used for decades to prevent the onslaught of American-style skyscrapers on Sydney’s city centre. The Act, known as the “anti-skyscraper law,” was driven by fears that tall buildings were particularly vulnerable to the ravages of fire. Sydney’s CBD had been scarred by the events of 1901, when a massive fire in an eight-storey department store resulted in five deaths, including a young man forced to jump from a window in front of lunchtime crowds.

Gamechanger: the newly completed AMP Building in Alfred Street, Circular Quay, in 1962. City of Sydney Archives

Melbourne, too, moved quickly to limit its building heights to 130 feet, a constraint maintained during the interwar period. Architects, firefighters, fire insurers and politicians were united in their view that any building exceeding the range of fire-fighting technologies was unsafe. As a consequence, for many years our cities continued to grow outwards, not up.

Many Australian urbanists of the early twentieth century considered tall buildings to be ugly expressions of the unbridled greed of speculative capitalism. As skyscrapers spread across America, Australian architects, including those working abroad, worried they would sully the rare beauty of Sydney and its glittering harbour. A group of architects, writing from London, called for special consideration to be given to Sydney as a city of rare beauty: “the idea that such an enormous asset as this beauty… should be so recklessly undervalued as to be left at the mercy of private speculation” gravely concerned them.

During this era, the ideal form of urban progress — or what we might now call “innovation” — was to be found in the pioneering form of the suburb. Though it later became unfashionable, the suburb was born of public health crises and designed as a harmonious balancing of privacy, hygiene and social cohesion. Where English cities had been afflicted by ill-planned slums that spread death and disease, Australian cities could experiment much more freely with new spatial configurations. Ready access to nature spaces, whether public parks or private gardens, gave rise to numerous planning laws explicitly designed to protect citizens from ill-health.

This aspirational urban form emerged in the 1830s, when the wealthy and well-educated looked to the ideas of Scottish gardener and publisher John Claudius Loudon, who popularised the potential of the “suburban villa with garden attached” to create health and happiness. Another Scotsman, biologist Patrick Geddes, would devise novel ways of seeing the city as a “bio-social” unit, taking account of health, ecology and wellbeing.

Shocked by the overuse of slum clearance to eradicate disease in India in the late 1800s, Geddes, now credited as one of the founders of the urban planning movement, pioneered a different kind of public health response to city pestilence. Governments, he argued, should not only clear away slums, disrupting countless lives, but design more intelligently, placing large gardens and parks, offering fresh air and communal spaces, at the centre of communities.

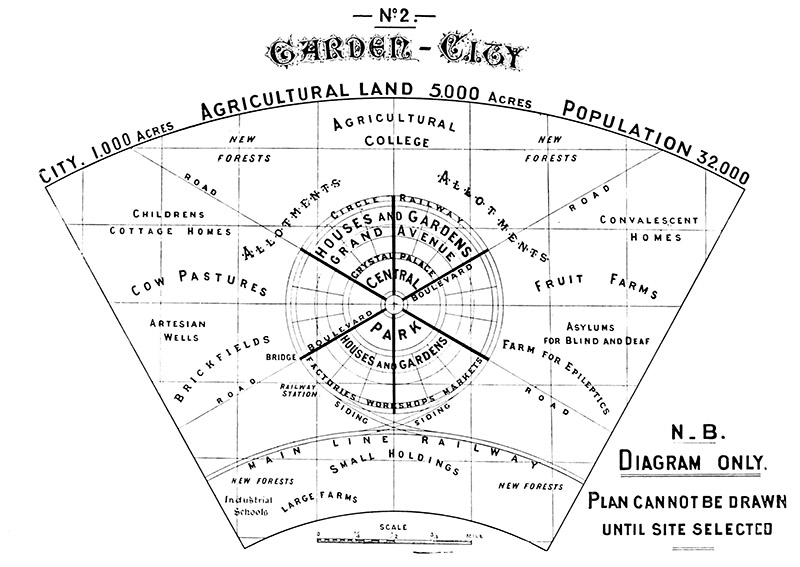

Likewise, the influential idea of the “garden city,” which gained expression across English and American cities and suburbs after the first world war, was seen as a way of improving the health of the working classes. Devised by planner Ebenezer Howard, it aimed to better integrate the experience of town and countryside, doing away with the crowded and unhealthy experience of the inner city.

Health Living: City Planning Diagram 2, from Ebenezer Howard’s Garden Cities of To-morrow (Swan Sonnenschein & Co., Ltd, 1922)

So, if today’s coronavirus sparks a rapid dispersion from dense urban cores, it certainly wouldn’t be for the first time. But nor would it mean an end to the city as such. If public health crises of earlier eras gave us suburban ideals of healthy living and generous urban parks for our leisure, the lasting changes resulting from this pandemic may well lie in the new spatial patterns that emerge from how we work.

Gone like a flash, perhaps forever, is the expectation that work necessitates being in an office; just as the “internet” is no longer a thing to dial up. It’s been fifteen years since Australian urban futurist William Mitchell decried as obsolete the workplaces of the industrial revolution, those essentially Taylorist constructions that required working at the same place at regimented times. And yet it took invisible strains of virus, not wireless broadband, techno-utopianism or even the rise of a knowledge-based workforce, to accommodate widespread teleworking.

From open plan to open air?

So what comes next? When you listen to those with a stake in commercial property markets, this is just a blip. Businesses will still need their offices to differentiate themselves, cultivate workplace culture and attract the top talent. But why exactly should workplace culture and connectivity only be forged in an office?

The answer may lie in reassessing the very function of the “work space” and its role in an organisation. Many are now rethinking what these spaces need to feel like if they are focused less on providing technology for computer-based tasks — after all, these can be done anywhere — and more on the need to promote workplace culture and nourish wellbeing. These spaces must now be “healthy” — with the “healthy building” tag now a feature of premium office spaces that tout their superior air and variety of lifestyle support services. Office space designers are embracing a greater symbiosis between natural and built forms, known as biophilia, interweaving green walls, natural materials and outdoor spaces. The airconditioned nightmare of the modern, monotonous layout just might be coming to an end.

For an image of what this might look like, look at Atlassian’s new headquarters next to Sydney’s Central Station. When completed, the tech company’s headquarters are projected to be tallest hybrid-timber building in the world, featuring elevated parks, mass timber interiors and an energy-generating glass façade. This green vision accompanies the recent announcement by Atlassian’s founders that employees may work from home permanently if they choose. No doubt they expect the quality of this space to attract plenty of tenants, if not their own workers.

Beyond changes to the look and feel of premium office spaces, we should also recognise something more radical going on. The nature of work is finally catching up with the affordances of digital tech. Distances are dematerialised; computing is “ambient”; organisations are becoming more “liquid.” My colleagues may be as much in Sydney as in Singapore. The local is no longer a place to depart in the morning, but a space to dwell in while working.

Like the radical suburban experiments of a bygone era, this public health crisis may yet allow for renewed kinds of making and connecting in previously dormant suburbs and neglected peripheral spaces. It may not be a “flight to the suburbs” in a retrograde sense, but a casting off of rigid modes of separation between home and work, industry and nature, as expressed in city forms. Australia’s suburbs may yet be well-suited to a coming era of biophilic urbanism, one that embraces “green infrastructure,” regenerative agriculture and productive allotments of either low or high-density urban farms.

Indeed, many are calling for more urban farming in a post-pandemic era, building in more local, resource-efficient food supply chains across suburban landscapes. Start-ups are springing up to deliver modular, stackable, automated vertical farms. With the right vision, the sleepy Australian suburb, places we once left for a busy day in the office, may again prove vital to a healthier urban future. For those like Rebecca Scott, chief executive of Melbourne social enterprise STREAT, post-pandemic Melbourne needs to be imagined as a “huge, edible urban food bowl,” a productive foodscape created by supercharging investment not just in green infrastructure but edible infrastructure as well.

If escaping pestilence and plague gave us the suburban dream, perhaps this pandemic will seed new patterns of work–life dreaming across the low-rise landscapes of the Australian suburb. Imagine a localised urban food hub in your area that also includes co-working spaces, tech supports, arts spaces and some outdoor dining. Would you return to the CBD? Perhaps only sometimes. But meanwhile, food supply chains would be diversified, carbon offset, water saved, transport networks declogged, with working families given more time, perhaps, to spend together.

Of course, these are just speculations. Perhaps train stations in the CBD will again be at bursting point during peak hour before too long. But as previous generations of urban visionaries and designers remind us, public health crises are often times of intensive urban innovation, when radical ideas actually gain purchase and are put into action. Perhaps this, too, will be one such time. •

Funding for this article from the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund is gratefully acknowledged.