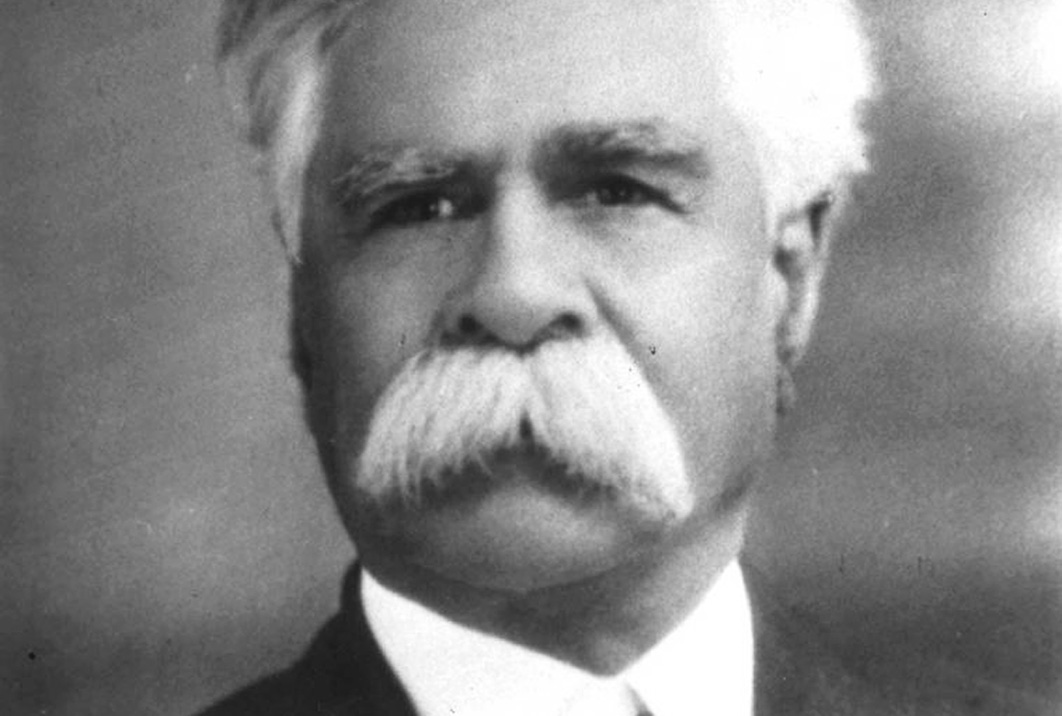

As recently as the early 2000s the Aboriginal leader William Cooper (1860–1941) was barely recognised in his own country. But he has been celebrated in recent years, and this greater recognition can be attributed to a story that has come to be told about him: the story of “the man who stood up to Hitler.” The story’s origin lies in a verifiable event: in December 1938 the Australian Aborigines’ League, an organisation headed by Cooper, tried to present a petition to the German consul in Melbourne protesting against Nazi Germany’s persecution of Jewish people the previous month.

That fragment of a story began its evolution when the well-known Melbourne Aboriginal activist Gary Foley came across a brief report about the event in a newspaper of the time. In an essay published in 1997 he drew a connection between the League’s protest and the event now widely known as Kristallnacht, a Nazi-sponsored pogrom against Jewish people. Foley believed the League was the first group in Australia to try to formally protest against the German government’s persecution of Jewish people, but his main aim was to draw attention to Australia’s persecution of Aboriginal people by noting the comparison with the Nazis.

The story Foley told about the League’s protest piqued the interest of staff at Melbourne’s Jewish Holocaust Museum and Research Centre (known widely at the time as the Jewish Holocaust Centre). It no doubt struck them as a good example of a people seeking to combat racism, and especially anti-Semitism. Telling a story about it would be a means of advancing the centre’s educational goal.

In the years that followed, the thread of the story told by Jewish institutions and organisations, here and in Israel, solidified into the account we know today. The protest at the consulate was the heroic work of one man, William Cooper, rather than the political organisation he represented, let alone any broader political movement of which it was a part.

According to this account, Cooper’s was the only non-governmental protest made in Australia, or even the world, against the Nazi persecution of Jews. In raising his voice, Cooper was bearing witness to the Nazi genocide of European Jews. His act sprang from his courage, humanity and compassion, and his empathy with the Jewish people, rather than any intention to advance his own people’s interests. It was all the more remarkable and worthy because he was standing up for the rights of Jewish people despite having no rights himself.

How did the story come to take on mythological qualities in this way? When they learned of Foley’s discovery, leading figures at the Holocaust Centre may well have also been influenced by two other narratives: that Kristallnacht was a turning point in the history of Nazi Germany’s treatment of Jewish people, which culminated in the Holocaust, and that tens of millions of gentiles had stood by while the Holocaust took place.

Foley’s argument that the League had been the first Australian organisation to raise its voice against the pogrom provided a striking counterpoint to the behaviour of other bystanders, or so it was believed. Just a few years earlier, Steven Spielberg’s remarkably popular Hollywood movie Schindler’s List had told a similarly uplifting story about an unlikely figure who rescued hundreds of Jews from the Nazi genocide.

I imagine the Holocaust Centre — and Melbourne’s Jewish community more generally — would also have been attracted to the story of the League’s protest because a particular kind of politics had become increasingly influential in Australia and many other Western societies — the politics of recognition, whose key words included remembrance, rights and reparation. Many non-Aboriginal people, or at least Anglo-Australians, now felt moved to tackle what was called “the great Australian silence” about Australia’s history of Aboriginal dispossession, displacement, destruction and discrimination. Increasingly, some were characterising this history as genocide — most recently in a report for the Australian Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission about the stolen generations.

The Holocaust Centre’s key figures would likely have been influenced, too, by a shift in how the past was being recounted and how people were relating to it, namely the rise in both scholarly and public circles of what was called “memory,” especially in the form of testimony, which had occurred most notably in accounts of the Holocaust. Those who had experienced a historical event had come to be seen as the most authoritative bearers of the truth about the past, so much so that “memory” was increasingly regarded in the media, and even by some scholars, as a substitute for history as told by academic historians, rather than just a supplement to those accounts.

An emerging scholarly and popular discourse also encouraged dividing those present in difficult historical circumstances into perpetrators, victims, collaborators, bystanders and resisters. In the case of settler societies, Indigenous people were called on to recall the past as victims; and non-Indigenous people were urged to listen to their testimony, acknowledge the truths they uttered, recognise the pain they had suffered, repudiate a past in which European ancestors were held to have been perpetrators, collaborators or bystanders (though sometimes resisters), and make amends for its legacies.

Over many years, this story has been told repeatedly in myriad forms outside the Jewish community: in commemorations, memorials, exhibitions, re-enactments, naming ceremonies, news reports, radio programs, books, magazine articles, essays, plays, paintings, musical compositions, blogs, videos and podcasts. It has been taken up by numerous government institutions and embraced by many sympathetic Anglo-Australians.

In December 2010 the largest and most senior Australian parliamentary delegation ever to visit Israel travelled to Jerusalem to participate in a series of events commemorating the League’s protest. In November 2017 a representative of the German government responsible for relations with Jewish organisations and issues relating to anti-Semitism, Felix Klein, accepted a document purporting to be the petition in Berlin, and in December 2020 he issued a formal apology for the German consul’s refusal to accept the petition some eighty years earlier.

In Australia, government bodies decided to name places in Melbourne in Cooper’s honour — a federal electorate, a building that houses several law courts and legal tribunals, an institute at a university, and a footbridge at a train station — and in each instance reference was made to the protest to the German consulate. The Aboriginal filmmakers Rachel Perkins and Beck Cole saw no reason to discuss the protest in their 2008 documentary First Australians; in 2020 the Aboriginal radio broadcaster Daniel Browning commissioned an episode of the ABC’s AWAYE! about Cooper that was framed by the story.

Cultural institutions have followed suit. The National Museum of Australia’s website feature “Defining Moments in Australian History” includes the story. Heritage Victoria has taken an interest in two of the houses in which Cooper lived, each of which displays an account of the story. The Victorian government department of education and training has included the story in its curriculum. And a historical society in Cooper’s traditional country has created an online exhibit about Cooper that focuses on the protest to the German consulate.

In the account of the protest I give in my life history of William Cooper, key historical facts are different. For example, the deputation to the German consulate can’t be attributed to Cooper alone, for while he was the Australian Aborigines’ League’s principal figure, League members (who included a whitefella by the name of Arthur Burdeu) played a major role; and the League, let alone Cooper, was by no means the first in Australia to formally protest against the Nazi German persecution of Jews after Kristallnacht, for two left-wing organisations had already tried to deliver a protest to the consulate in Melbourne. Nor can we be sure that Cooper was present when the attempt was made to hand over the petition — indeed, it is quite likely that he was not, as his health had declined considerably by this time.

More importantly, in the story that I tell, the meaning of this event is different. My point of departure is that the League was quintessentially a political organisation — and an Aboriginal one at that — and that it consequently went about its work in a strategic fashion, always considering what might be the best possible ways to fashion a case that could persuade white Australians to support its struggle to improve the lot of its people.

In the month prior to drawing up its petition, the League had evidently been conducting much of its political work by drawing parallels between Nazi Germany’s persecution of Jewish people and more than one Australian government’s treatment of Aboriginal people. It pointed out that the persecution of Indigenous people in Australia was akin to that experienced by racial minorities in Europe, and asserted that Australia should be as concerned about the rights of its people as it was about the rights of those other minorities.

One sentence in particular in the League’s petition — or what has survived of it — provides evidence that this was the point of its protest: “Like the Jews, our people have suffered much cruelty, exploitation and misunderstanding as a minority at the hands of another race.”

Other parts of the historical record also suggest that the League’s protest sought to draw attention to similarities between the treatment of the Jewish minority by the Nazi German government and the treatment of the Aboriginal minority by Australian governments.

Barely ten days after the League left its petition at the German consulate, a letter in Cooper’s name sent by the League to a federal minister said, “We feel that while we [Australians] are all indignant over Hitler’s treatment of the Jews, we [Aboriginal people] are getting the same treatment here and we would like this fact duly considered.” Several months later, in a letter now held in the National Archives, Cooper told prime minister Robert Menzies, “I do trust that care for a suffering minority will… not allow Australia’s minority problem to be as undesirable as the European minorities of which we read so much in the press.”

Shortly afterwards, following the outbreak of war, Cooper spelled out the kind of connection he and the League were trying to make in protesting against the Nazi persecution of German Jews. “Australia is linked with the Empire in a fight for the rights of minorities…” he told Menzies. “Yet we are a minority with just as real oppression.” A year later, Cooper’s protégé Doug Nicholls posed this rhetorical question to a congregation in a Melbourne church: “Australians were raving about persecuted minorities in other parts of the world, but were they ready to voice their support for the unjustly treated Aboriginal minority in Australia?”

My interpretation of the League’s protest rests not only on these written historical records but also on a source that can be seen as the product of collective memory or tradition. About a year before the League’s deputation to the German consulate, Cooper, in the course of speaking at length to a white journalist, referred to his people’s “horror and fear of extermination,” saying: “It is in the blood, the racial memory, which recalls the terrible things done to them in years gone by.” (His most important political act, a petition to the British king, also expressed a fear of extermination by speaking of the need to “prevent the extinction of the Aboriginal race.”)

These statements give a sense that the League was drawn to make its protest to the German consulate because, consciously or unconsciously, its members identified themselves with German Jews as a result of their own people’s experience of violence.

The story I have told of the League’s protest makes clear that the story of Cooper as the man who stood up to Hitler has leached the event of the meaning it had at the time for those responsible for it, and the meaning it could have today.

In everyday parlance, “myth” refers to a statement that is widely considered to be false. In using this word to describe the story of Cooper as the man who stood up to Hitler I don’t want to exclude this connotation, but I have something more ambiguous in mind.

Most myths have a genuine link to a genuine past. To be considered plausible, an account of the past must have at least a partial relationship to past reality, and thus to what is regarded as historically truthful. In this instance, it is a historical fact that the Australian Aborigines’ League sent a deputation to the German consulate in Melbourne in December 1938 to present a petition in which it protested against the persecution of the Jewish people.

But the rest of the story is a good example of what the great British historian Eric Hobsbawm once called “the invention of tradition.” It has been created by projecting onto Cooper a purpose and a character that the storytellers wish him to have had. The historical fact of the deputation aside, none of the story has been formed on the basis of the historical record.

Like most myths, this story achieves its most powerful effects not by falsifying historical material — though one of the organisations that has played a leading role in producing the story has fabricated the petition the League presented to the German consulate — but through omission, distortion and oversimplification.

Consequently, Cooper is recognised not because of his people’s loss, pain and suffering, but because he recognised the Jewish people’s loss, pain and suffering. This is the point of the storytelling. As a result, the popular account deflects attention from the devastating impact of racism and colonialism on this country’s Aboriginal people, and their struggle to lay bare its legacies and get them redressed. Such can be the cunning of recognition. What might purport to recognise the history of Aboriginal people misrecognises it.

The degree to which this myth has distorted how Cooper should be remembered — and the costs of that distortion — is highlighted by comparing it with what Gary Foley was doing. He was practising history in keeping with the discipline’s protocols, which include the recovery of the relevant historical texts and historical contexts, and was also adopting the techniques of Aboriginal history, a subdiscipline that seeks to make sense of the past and its presence by engaging with Aboriginal historical sources, subjects, agency and perspectives. The evolving story of Cooper’s protest ignored Foley’s main aim: he was seeking to draw attention to parallels between the murderous Nazi German campaign against the Jews of Europe and what had happened and was still happening to Aboriginal people in Australia.

In Australia, as elsewhere, history as a way of knowing and understanding the past threatens to be displaced by myth and memory (or what is deemed to be memory) that make claims about the past that are seldom tested and provide little explanation for what happened and why. Yet, as historian Allan Megill has suggested, “truth and justice, or whatever simulacra of them remain to us, require at least the ghost of History if they are to have any claim on people at all. What is left otherwise is only what feels good (or satisfyingly bad) at the moment.” •