Acres of ink and gigaloads of bytes have been spilled in recent times over “free speech.” Sadly, the debate has mostly been self-serving. Much of it has been driven by right-wing voices opposed both to vilification laws and to a now-defunct proposal to strengthen the press complaints system. Left-wing voices, while less prominent, have focused on gags on public servants and moves to stop grant funds being used to advocate for policy reform.

Balancing liberty of expression with civility and equality is not simple. True conservatives emphasise the need for respectful debate and defend the concern for reputations embodied in defamation laws. Progressives fret about power, and the need for marginalised voices to have an equal share of the stage. Small “l” liberals want to leave things to the marketplace and see the internet as a liberating agent. These are all principled positions. Freed of posturing, most people would agree we need to find some balance among them.

The current debate has largely been driven by self-described liberals – “self-described” because they tend to have motes in their eyes. Either that, or they are aroused by passing controversies or old cultural battles as much as any deep commitment to liberty.

Two causes célèbres have animated the George Brandises and the Tim Wilsons (the attorney-general and his human rights commissioner are the best exemplars) to declare themselves to be the living embodiments of J.S. Mill. One was the civil suit against columnist Andrew Bolt for vilifying prominent “light-skinned” Indigenous figures. After Bolt was required to apologise by the Federal Court under the Racial Discrimination Act, senior Liberals and the Institute for Public Affairs campaigned relentlessly to gut the law. But then, in a volte-face last week, the prime minister abandoned the idea, not because he felt that the law was necessary to modulate aggressive racialism but because he risked too much political capital to have it repealed.

The other agitation was provoked by the Gillard government’s interest in regulating the press rather than persisting with a system of self-regulation, which newspapers enjoy but broadcasters do not. After a public inquiry, and echoing similar British proposals, Justice Ray Finkelstein recommended a speedy conciliation process for complaints against newspapers and a new body with the power to order apologies and corrections. As in the Bolt controversy, News Ltd led the opposition. One irony is that Bolt could have been sued for defamation rather than judged against the Racial Discrimination Act, which would have cost his employer News Ltd much more than an apology; another irony is that Finkelstein’s recommendations would have bypassed defamation law, with its expensive lawsuits and chilling effects.

There is undoubtedly a principled ground for objecting to racial vilification laws. Where vilification falls short of incitement or intimidation, such laws may do more harm than good. They may martyr bigots, and suppression may breed more prejudice. The pragmatics of press regulation were different: Finkelstein’s approach to complaints was rational but it was twenty years too late, impractical in an era of lightning-fast, decentralised internet news sources.

But we should judge these new Millian liberals not just on what they say, but also on what they don’t say, and on what they do. Last year, in Monis’s case, the High Court upheld charges against two Muslim Australians who had used the postal service in an “offensive” manner by sending spiteful letters to the families of servicemen who died in Afghanistan. The principal defendant, Monis, saw that war as a Western invasion.

Bolt’s was a civil matter, involving a journalist publicly traducing reputations. Monis’s was a criminal case, involving private communications. It was spiteful behaviour, to be sure, but also speech with a political point. The silence about Monis’s case and the underlying law, not just from Liberal politicians but from Labor as well, was deafening. Neither Millian liberals nor the tabloids invoked the principles of free speech to defend a Muslim Australian. Similar offences also apply at state level and to the internet. It would take a Stasi-like police force and an American-size prison capacity to enforce criminal laws for every “offensive” online communication.

The mote-in-the-eye goes beyond just the problem of selective outrage. The Abbott government has introduced measures to restrain the public political speech of two groups: public servants and certain non-government organisations receiving Commonwealth funds. Both measures are the result of executive fiat rather than parliamentary deliberation. The new public service rules warn public servants against expressing even anonymous opinions on social media if they could be regarded as treating government or opposition policy in a “harsh or extreme” manner. Public servants with professional or community roles, such as in an environmental group, are also warned about criticising government policy on, say, wind farms.

A dictate against NGO advocacy is now included in the “service agreements” these organisations must sign with the government. Some 140 community-based legal centres, for example, will be banned from using any of their funding for law reform advocacy. This might be understandable if there were any sign that the government was committed to better funding of services in the longer term; after all, in times of fiscal constraint, directly helping clients is more of an imperative than longer-term lobbying. And, as Indigenous arts advocate Wesley Enoch said recently, NGOs that rely too heavily on government money are always at risk of capture.

But as the Productivity Commission has observed, and ombudsmen everywhere recognise, social problems can’t be dealt with only by applying bandages. They often require a systemic push for reform. In a case involving the foreign aid organisation Aid/Watch in late 2010, no less a body than the High Court held that charities ought not lose their charitable status simply because they also act as public advocates. Informed public debate – in this case about the best measures to advance charitable relief through government aid – is in itself a contribution to public welfare.

The underlying issue, of course, is that the government sees ideological enemies everywhere: in the public service, in NGOs and in the ABC. The tendency to compromise principles out of partisan concern is hardly a new one. Liberals in the past have been willing to compromise their liberal instincts to advance their incumbency, just as Labor governments have. When compulsory voting was introduced a century ago by the last Liberal government in Queensland, for instance, a big part of the motivation was conservatives’ jealousy of the ability of unions to mobilise electors under voluntary voting.

Libertarians reflexively object to taxpayer funds supporting any form of political or policy-related speech. But that pure ideological position is not practised by any government in Australia. Tax law allows corporations to deduct the cost of campaigns against laws and policies that affect their business. Trade union dues are tax-deductible, too, as are donations of up to $1500 to political parties – a nice subsidy to the political leanings of higher-income earners. And tens of millions of dollars of public funding of parties, as well as unlimited government advertising budgets, are justified in the name of “clean money” and “public information.”

The Liberal National Party government in Queensland has just awarded itself the lion’s share of a new, annual stream of “policy development funding” for the major parties in that state. This came just months after it had legislated to hamstring unions seeking to spend $10,000 or more on “political” speech. (That anti-union law is now repealed, not on principle but because the government feared an adverse High Court ruling.)

Part of the problem is that modern-day liberals conceive of freedom of speech in a stunted way, as merely a negative liberty. It is the freedom of magnates to run a political party or a multimillion-dollar campaign against the mining tax. But what if you lack the resources for such megaphone speech, if you are one of the disaggregated voices of the unemployed or micro-business? To paraphrase Anatole France, in its majestic equality our law allows everybody, equally, to own a media empire or to risk arrest holding a placard at a demonstration.

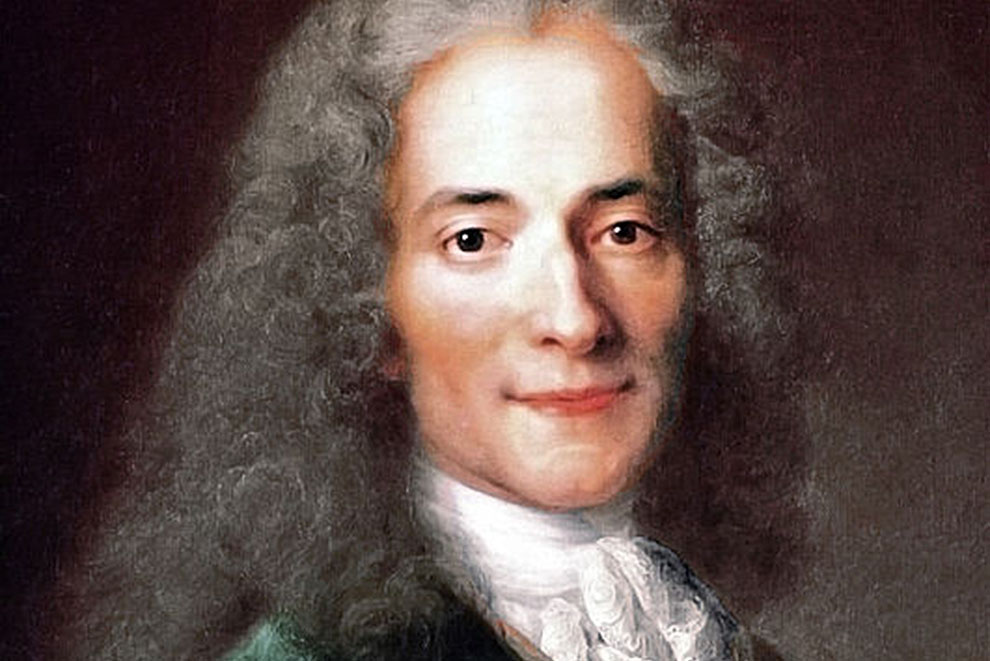

The other problem is less philosophical. In an environment more partisan than principled, that old dictum of another French writer, Voltaire, has been recast. Today, it is less a case of “I disagree with what you say, but will defend to the death your right to say it” and more a case of “If I don’t agree with what you say, I will defend to the death my right to be a hypocrite.” •