It’s been forty years since Mark Aarons, an ABC reporter, broke the news that Nazi war criminals were living in peaceful obscurity in Australian suburbia. What followed was astonishing for a country prone to burying its head in the sand about the past activities of some of its European immigrants. In the face of deep scepticism from his cabinet, Bob Hawke backed the creation of the Special Investigation Unit, or SIU, a taskforce to investigate and prosecute alleged war criminals from the second world war.

Under the leadership of Bob Greenwood QC and the Australian Federal Police’s Graham Blewitt, the SIU gathered an impressive team of police investigators, most of whom might have heard only vaguely about the Holocaust and never have left Australia. They worked alongside historians, archaeologists, translators, researchers and lawyers to uncover the forensic history of the “Holocaust by bullets,” the mass extermination of Jews in mass graves across a region that encompassed the Ukraine, the Baltic states, Poland and ex-Yugoslavia. The newly released Nazis in Australia, compiled by Blewitt and edited by Aarons, is a deeply reflective account by some of the key players involved in the SIU during its five-year history.

We are accustomed to thinking of that history as a failure. Of the 841 cases of suspected war criminals opened by the SIU, only three were committed to trial and none were punished. The unit was abruptly closed down just when it was about to submit its biggest mass murderer to the Commonwealth director of public prosecutions. Its final report was quietly buried by a Keating government unwilling to alert the public to its decision to abandon the search for justice.

But the SIU was in many ways groundbreaking. Bob Greenwood QC secured a mutual assistance treaty with the Soviet war crimes procurator — the formidable Natalia Kolesnikova, infamous for her unbending attitude to Western investigators — that gave his investigators access to archives, eyewitnesses and the hidden crime scenes of the second world war. It was a cold war precedent that neither the Washington-based Office of Special Investigations nor the Canadian war crimes unit had been able to achieve, and facilitated a rare moment of cooperation between Australians, Ukrainians and Soviet officials. It also gave Australian researchers access to archives never before visited by Western historians.

The SIU also set a precedent in Australian criminal legal history, establishing for the first time the ability of a jury trial to prosecute international war crimes. In further firsts, mass graves were located and excavated, bodies exhumed and victims finally given a decent burial. Eyewitnesses were finally able to speak about atrocities they had seen unfold, or even participated in, forty-five years earlier. Some left their villages for the first time to travel halfway across the world to give their testimony in a Western courtroom: also a world first. Interpreters and translators rewrote the rule book for assisting in war crimes trials off the back of these events.

Perhaps most importantly, though, the SIU showed it was possible to investigate war criminals for crimes committed outside Australia in conflicts without Australian involvement. This entailed amending the War Crimes Act, originally legislated in 1945 to prosecute Japanese war criminals, and inserting a new section that mandated a fair trial, a requirement missing from the original legislation.

When it came to finding justice for their victims, however, the SIU’s record is more complicated. Of the hundreds of names it investigated, only three cases were formally recommended for prosecution, Ivan Polyukovich, Heinrich Wagner, and Mikolay Berezowsky, each of whom was alleged to have committed atrocities in the Ukraine.

Polyukhovich, a forest warden working for the Germans in a village called Serniki, deep in the Ukrainian marshes, was alleged to have been intimately involved in the murder of between 553 and 850 Jewish locals. “As the bodies were exposed,” Australian archaeologist Richard Wright writes, “it was clear the murdered Jews were made to lie down like sardines in a tin before being shot.”

Wagner, a member of the local gendarmerie in a village called Ustinovka, allegedly organised the digging of a mass grave, participated in the killing of adult Jews into the pit, and then ordered all the children of Jewish descent in the village to be rounded up and thrown on top of the adults, where they were shot.

Berezowsky, head of the local police in Gnivan (now Hnivan), near Vinnytsia, was allegedly involved in the mass murder of the Jewish population of Gnivan, mainly women, children and the elderly, between March and July 1942. One eyewitness claimed he had rifle-butted a baby to death in its mother’s arms.

These three men, and other alleged war criminals discussed in this book, all arrived in Australia as part of the mass postwar immigration scheme designed by Ben Chifley’s Labor government to help fill the shortfall in manpower required for Australia’s postwar reconstruction program and counteract what appeared to be a declining birthrate. Between 1947 and 1952, more than 170,000 people came to Australia via the “displaced persons,” or DP, camps of postwar Germany. There, around one and a half million Eastern Europeans remained under Allied care after refusing to return to their countries of origin now under Communist rule. Many had been victims of the Nazis, but others had slipped into the camps after retreating with the Germans from Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union and then lied about their past activities.

Before being accepted for immigration to Australia, DPs were required to pass security and medical screenings by the Allied-run International Refugee Organization and then by Australian officials. Germans, war criminals and Nazi collaborators were ineligible for DP status under IRO rules, but in reality plenty were able to slip through the net, claiming to have lost their identity papers, for example, and lying about their whereabouts during the war.

Moreover, Australian selection officers were less interested in candidates’ recent pasts than whether they were a suitable “type” of migrant. Equipped with a strong sense of national responsibility but a vague knowledge of European politics, European languages and complicated European geography, officers relied heavily on the IRO’s security screenings, flawed foreign intelligence and doubtful interview techniques.

Most of the Australian migration selection officers had military backgrounds and received little if any training before arriving in Europe. Australian ex-serviceman Mort Barwick was among them. “There were no specific instructions as to what type of person we should take,” he recalled, “provided they were of reasonable standard and in your opinion could assimilate into your community, then it was a question of, if you were satisfied, select them.”

The emphasis was on those who, on the face of it, wouldn’t threaten the White Australia demographic. Those from the Baltic nations (Lithuanians, Estonians and Latvians), along with Ukrainians (a dubious category at the time), were considered most desirable. Jews were placed at the bottom, with Poles somewhere in between.

By the late 1940s, the deepening cold war was shifting the priorities of the Allies away from punishing West Germany to encouraging its peacetime reconstruction. It was also redefining the category of refugee. By the end of the decade, a professed fear of communism weighed more in a DP’s favour than proof of actual persecution under the Nazis. Those who may once have been condemned on the grounds of Nazi collaboration, for example, could now find themselves reassessed as heroic freedom fighters against communist tyranny.

Australian migration officers were encouraged to participate in this wilful revisioning of history. As historians have correctly observed, most recently Jayne Persian in her excellent book on the topic, Fascists in Exile, security screening was notoriously lax. Australian selection teams focused on admitting preferred racial types (fair-skinned) with the correct anti-communist views. Consequently, a number of fascists, war criminals and Nazi collaborators were able to come to Australia as DPs without fear of prosecution. Most did not even bother to change their names.

Combined with political inertia, it was this kind of wilful ignorance that determined attitudes to alleged war criminals. During the 1950s, allegations mainly from the Jewish community that Nazis who had participated in mass killings were living in Australia largely fell on deaf ears. In 1961, when the Soviet government requested the extradition of an Estonian man for war crimes, attorney-general Garfield Barwick called for an amnesty, telling the Australian parliament “the time has come to close the chapters on war crimes.”

Yet the shift that eventually led to the creation of the SIU was already in train. Accusations from overseas about Australia’s harbouring of alleged war criminals were becoming harder to ignore. The Eichmann trial in Jerusalem, the publication of Raul Hilberg’s groundbreaking The Destruction of the Jews and other new histories, and a generational shift in the 1960s and seventies were all increasing the pressure. By the mid 1980s, when Aarons broadcast his explosive five-part series on ABC radio, Australia was starting to look like an outlier among Western nations that were already acting to bring war criminals to account. Hawke commissioned an official inquiry in 1986 under Andrew Menzies; the SIU was established following the release of its report, which found seventy suspects who warranted further investigation.

Of the three men eventually recommended to the director of public prosecutions, only Polyukhovich made it to trial. Heinrich Wagner suffered a heart attack during the committal hearing, and his case was dismissed on the grounds that, according to the trial judge, “the risk of Mr Wagner dying in the course of his trial is, in my opinion, too great.” A disappointed John Ralston, the lead investigator in Wagner’s case, believed the proper route would have been a temporary stay of proceedings to see whether Wagner could recover to stand trial. Mikolay Berezowsky’s case was dismissed on the grounds of insufficient evidence, another disappointment discussed in a chapter by Graham Blewitt.

Ivan Polyukhovich’s case is perhaps most revealing of why Australia appeared unable to provide just outcomes. A lot appeared to go wrong. For a start, only two of the original thirteen charges were allowed to proceed. The judge severely limited the evidence that could be shown to the jury and, worse, restricted the matters on which the historical experts could opine. The Ukrainian witnesses, who had travelled to Adelaide to participate in the trial, were bewildered by the process, contradicting their own statements in court and confused by the cross-examination. But perhaps most damaging to the prosecution was the summing up by Justice Cox, who all but prejudiced jury members against a guilty verdict, openly telling them it would be dangerous to convict after all these years.

Blewitt is perhaps the bluntest in his account of the judge’s conduct. “I thought we didn’t get a fair deal at the trial,” he has stated. In prosecutor Grant Niemann’s words, Cox “summed up to the jury for an acquittal, and that is what they did.” In the space of an hour, the jury found Polyukhovich not guilty on both counts. He was free to go.

Niemann and other contributors to Nazis in Australia believe the problem was larger than Cox. A jury trial, Niemann writes, was an unsuitable vehicle for a Nazi war crimes trial. “No matter how egregious Hitler’s ‘final solution’ was, it might be difficult for an Adelaide jury to relate to something that happened in German-occupied Ukraine nearly fifty years earlier,” he argues, “during the course of a war only remotely connected to them, and in a theatre of war in which Australia played no part.” Instead, the jury saw a sick, old man.

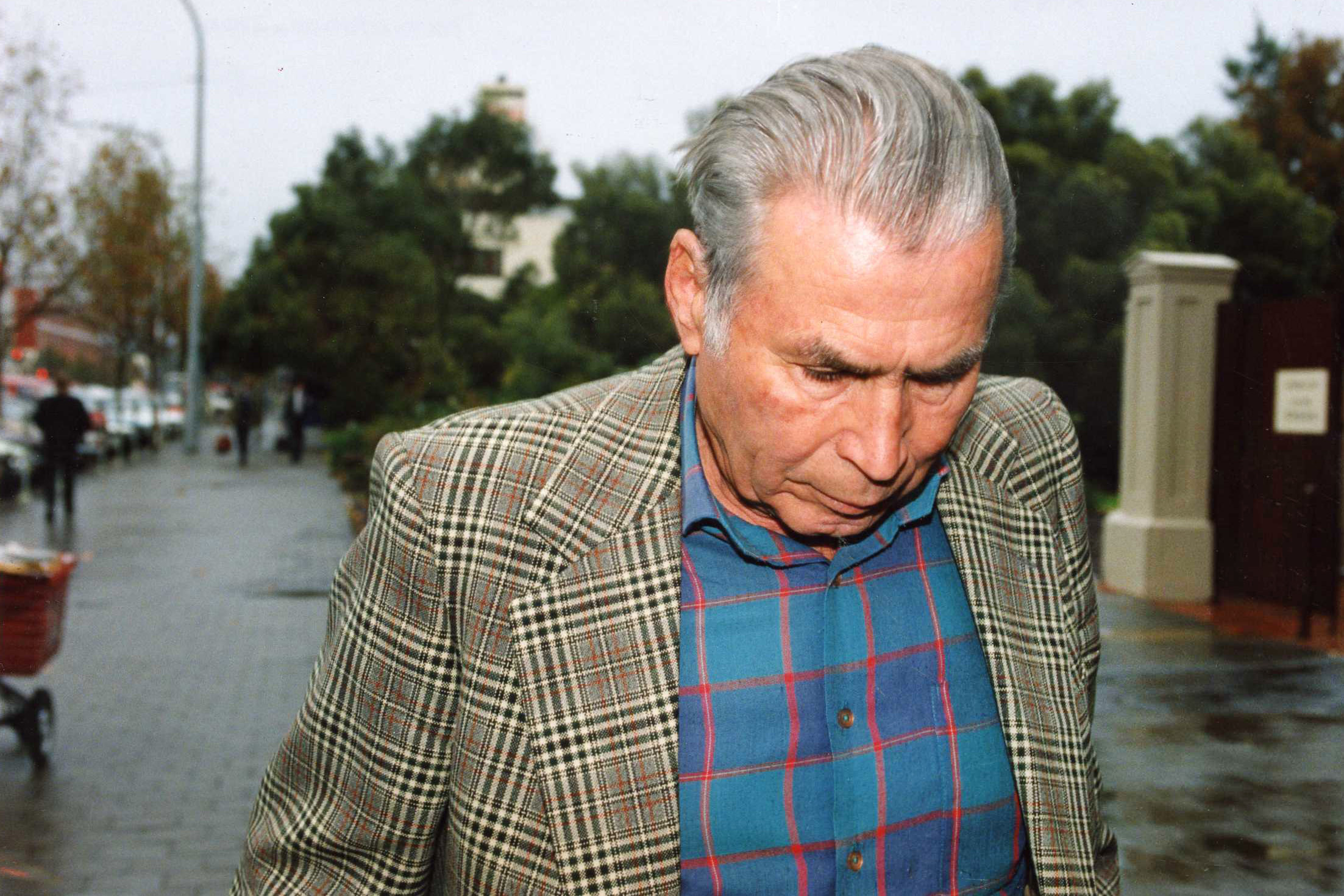

As Jürgen Matthäus, an expert historian, writes, “the media-driven image of agile Nazi perpetrators in black uniforms and animated by murderous fervour clashed with the portrayal of alleged war criminals as elderly, polite and inconspicuous neighbours whose normal postwar life made their association with Hitler’s mass murderers seem dubious.”

Indeed, it was these attitudes that drove the hostility of the media towards the trial — then, and since. Twenty years after the SIU was shut down, I investigated the case of Károly Zentai, an Australian man wanted for extradition for war crimes in his country of origin, Hungary. I found that the general attitude of the Australian media and the public was of sympathy for Zentai, portrayed as frail and elderly, who had led a largely blameless life in Australia and was being pursued for something that may or may not have happened a long time ago. As I wrote in Inside Story, the links that were forged in the postwar era between Australia and Eastern Europe via its mass migration schemes were also bonds of complicity in the project of forgetting and denial that has governed the politics of justice.

An investigation of a Latvian man called Karl Ozols was almost complete when Paul Keating decided to end the work of the SIU in 1992. Ozols was perhaps the most serious war criminal investigated by the SIU, and his was the case that might have come closest to a guilty verdict. He was a commander of a particularly murderous Latvian SS unit believed responsible for around 30,000 deaths. Another alleged war criminal, Argods Fricsons, head of Riga’s Kurzeme District Latvian Political Police, was accused of directly participating in the murder of 40,000 people in Liepāja. Both men were allowed to live out their lives without seeing the inside of a courtroom. Ozols died at eighty-eight in 2001, Fricsons at seventy-five in 1990.

There is a sense that this book has been a long time coming — that the time has come to break the silence about what the SIU experienced at the hands of a hostile media and judiciary, and about the short-sighted politics that led to the unit’s closure. Although careful in their accounts, the participants’ disappointment is palpable. Yet all remain convinced that it was the right thing to do. The work was clearly life-changing for all involved, deeply affecting both professionally and personally. Some went on to work for the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia: Blewitt became its deputy prosecutor.

Australia has still not developed the legal framework or the investigatory resources needed to find and prosecute people who have committed war crimes in any conflict overseas. In a report for the Lowy Institute, former diplomat Fergus Hansen noted that this country “has inadvertently become a safe haven for war criminals.” This is certainly the impression Australia has been giving the world, and presumably its war criminals, for quite some time. •

Nazis in Australia: The Special Investigations Unit, 1987–1994

Complied by Graham Blewitt, edited by Mark Aarons | Black Inc. | $39.99 | 320 pages