The best reason for not believing in the Judeo-Christian God is the suffering and evil that is so prevalent in our world. But people who experience terrible tragedies don’t often repudiate their God. Their suffering becomes a reason for adhering more strongly to their faith. Their belief in God fills a deep need that is not touched by the arguments of sceptics and atheists.

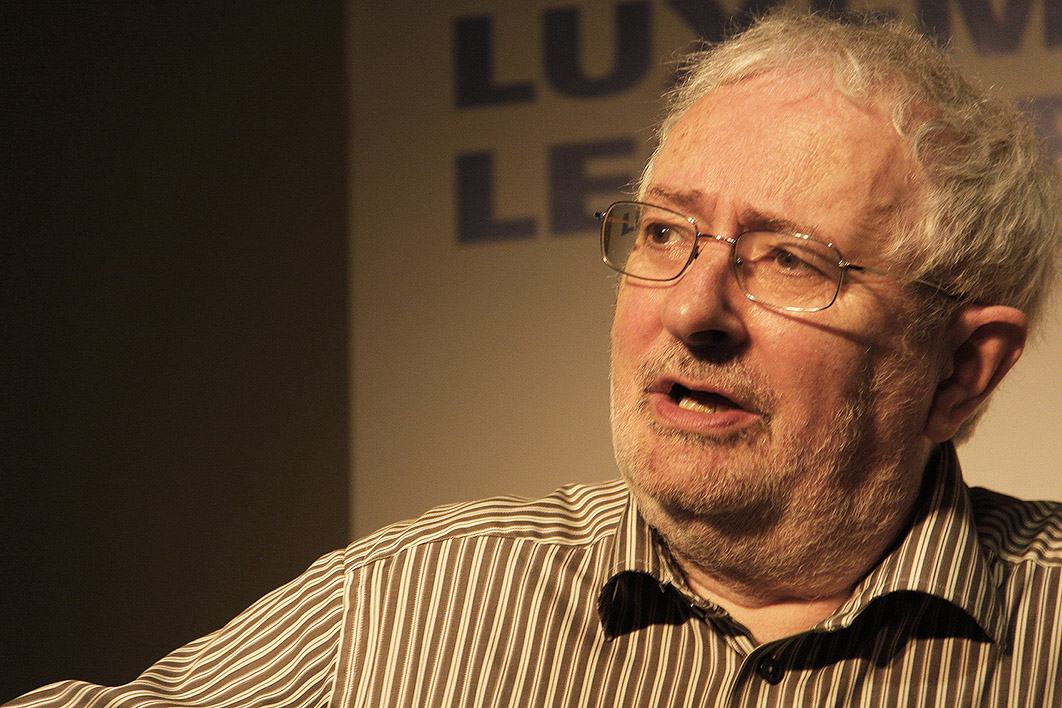

Terry Eagleton, distinguished professor of literature at the University of Lancaster, is a literary theorist, a cultural critic and an opponent of the “new atheism” of Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens. He opposes their views not because he wants to defend religion but because he thinks their position shows a lack of understanding of human psychology and society. Atheism, he says in his new book Culture and the Death of God, is not as easy as it looks. Though we live in a secular culture that seems to have little use for religion, we have not succeeded in killing off God.

Religion, Eagleton argues, fulfils two important functions. It not only sustains individual lives by providing meaning and values that transcend mundane existence; it has also provided the glue that holds societies together by motivating people to accept the sacrifices required by morality and political life. This was why rulers of eighteenth-century Europe feared the spread of irreligious doctrines: fears that translate in modern times into a concern about how a society driven by individual self-interest can hold itself together without some unifying force. Religion was able to fulfil these functions, Eagleton thinks, because it had the ability to appeal to rich and poor, to members of the intellectual elite and to uneducated people. It combined abstruse theory with imagery and ritual, intellectual rigour with an appeal to the senses.

“The history of the modern age is among other things the search for a viceroy for God,” writes Eagleton. But nothing has succeeded in filling the role: not reason, nature, spirit, art, imagination or even culture.

The Enlightenment failed to provide a substitute for religion because of the dry, abstract nature of its principles. As Eagleton puts it, “Reason cannot offer us ecstatic fulfilment, a sense of community or wipe away the tears of those who mourn.” Indeed, most Enlightenment thinkers had no intention of disturbing the faith of the masses.

Hegel, Schelling and other Idealists recognised the failings of the Enlightenment and attempted to find an absolute grounding for existence and human freedom in a free, harmonious, transcendent subjectivity. But their abstractions had no hope of filling the gap left by a loss of religious belief. For a time, art was given the task of connecting humanity with transcendent value. Romantics saw Nature or the imagination as a source of comfort, spirituality and revelation. But art appreciation is as remote from the masses as Enlightenment reason. Nature is cruel and the imagination can create horrors.

The most plausible substitute for religion, according to Eagleton, was culture as a form of cultivation that requires spiritual inwardness as well as respect for tradition. But it, too, failed in its ability to reach down from the lofty heights inhabited by an elite to the rest of the populace.

Eagleton’s complaint against all these attempts to provide a substitute for God is that they failed to motivate the masses. The exception is nationalism, and Eagleton makes too little of its ability to unify people and motivate them to care about the fate of each other. In this respect nationalism seems a better candidate than culture as a substitute for religion. It has been responsible for evil as well as good, but so too has religion.

A more basic reason why modern thought has failed to kill off God, in Eagleton’s view, is that it has taken over the trappings, doctrines and aims of religion and merely restated them in a secular form. Enlightenment thinkers and idealists, like religious ideologues, aimed to provide a universal foundation for morality and the law. Nationalism has its rituals and its saints in the form of national heroes. Art, nature and culture are supposed to introduce us to transcendent values.

Eagleton is following in the footsteps of Nietzsche, who was, he says, one of the few to recognise that the death of God also requires the death of morality and spiritual transcendence. But Eagleton points out that even Nietzsche failed to appreciate the implications of his own philosophy when he proclaimed the coming of the Overman as the superseder of craven, guilt-ridden Man.

Only postmodernism has truly brought about the death of God. A philosophy that doesn’t need or want unequivocal truths, that is not in search of foundations and has no truck with the self as a source of meaning, has no need for God or any substitute. But God refuses to stay dead. The needs that religion fulfilled have not gone away. The resurgence of religious fundamentalism, the war against terrorism as well as the divisive tendencies of consumer capitalism are driving people back to a search for the values and certainties that religion provided.

EAGLETON performs this march through the history of Western culture with verve and style. He is knowledgeable about literature as well as philosophy and he moves with ease from Coleridge to Fichte and from T.S. Eliot to Edmund Burke. He is the master of the pungent phrase and the witty aphorism. Sometimes he is inconsistent and sometimes he is unfair to the thinkers he discusses. Rushed along by his energetic prose, though, readers are not likely to mind all that much.

Eagleton is no fan of postmodernism and he doesn’t applaud its annihilation of religion. Though his purpose is not to defend religion or to offer a solution to our predicament, he makes a few gestures in the direction he thinks we must go to dissolve the forms of life that produce a need for religion. We need a morality that begins with the human body and makes a connection with lived experience. We need a religion that takes seriously the message of Christ and his solidarity with the poor and the oppressed.

There is nothing new about these ideas. Romanticism also emphasised the body and lived experiences. Philosophers since the Enlightenment believed that morality ought to be grounded in human needs and experiences. Many reformers and revolutionaries have taken Christ’s example to heart. These recycled materials seem a poor starting point for a radical change of consciousness and society.

Eagleton’s tentative prescriptions reveal an underlying tension. He is drawn towards the Marxist idea that the need for religion, and the reason for God’s refusal to die, is found in the nature of capitalist society rather than in the inadequacies of philosophy or the needs of the human heart. He emphasises the deficits of consumer capitalism: its sterility, its encouragement of a volatile and restless subjectivity that lacks firm beliefs or grounding convictions. Because “too much doctrine is bad for consumption,” postmodernism is the philosophy that suits it.

But postmodernism is not enough to do away with the deficit. Hence the resurgence of religion and extreme ideologies. This analysis suggests that a better society (though what form it would take is not clear) would eliminate the need for religion or any substitute. Social revolution, not philosophy, is needed to bring about the death of God. But Eagleton never says this because he is well aware that religion cannot be reduced to its social functions and that the quest for a basis for morality and the values required for social and political life is an enterprise that has to be taken seriously.

Is it true that this quest has discovered no substitute for God? In following Nietzsche down the path of nihilism Eagleton is predisposed to regard any pursuit of ideals, any adherence to an ideology, any appeal to moral values as religion in disguise. He criticises John Gray for this kind of reductionism, but he engages in it himself when he claims that philosophers who attempt to justify universal values are promoting religion in another guise.

To think that truth is important, to defend human rights, or to think that we have a duty to help the poor and oppressed is not the same as having a religion. One of the differences is the way these secular beliefs are justified and held. Religious prescriptions ultimately rest on an interpretation of scriptures as the word of God or the teachings of religious authorities. Secular morality and values are justified by appeal to needs or sympathies, communal loyalties or respect for human individuals (or living things or nature). Values can be dogmatically held and Eagleton is right to point out that some philosophers believed that reason could deliver indubitable moral principles. But for the most part we have become accustomed to uncertainty and to moral beliefs supported only by the best reasons we can come up with.

Uncertainty means that there truly is no substitute for religion. There is no secular doctrine that can do what religion was supposed to do: unite us all under the umbrella of a faith, provide us with unquestionable moral rules, tell us our place in the world, give us a meaning for our existence and a worldview that brings together facts and values, empirical laws and divine will. But then religion never really did those things – not even in Christian Europe. There were always people with different faiths or different interpretations of them. There were always dissenters and heretics. There were always doubts about the Christian story of creation, resurrection and redemption. Secularism merely added to or amplified challenges that already existed.

A faith that everyone subscribes to is not a possible or desirable objective – especially in a multicultural society that contains people of many different beliefs, as well as atheists and agnostics. It is a recipe for persecution and exclusion. This is one thing postmodernists got right.

Does it really matter that there is no secular substitute for God? Eagleton seems to assume that a substitute fails if it cannot do everything that religion did (and by religion he seems to have Catholicism mostly in mind). But it is more plausible to suppose that most of us find reasons for being moral and cooperating with others, and ways of finding life meaningful, by cobbling together all sorts of beliefs, ideals and emotional propensities: our sympathy for others, our ability to find value in nature, art or relations with others, our connection to our children and grandchildren, our work, our love of country or attachment to a community, and so forth. Religion, for those who have it, is part of the mix.

Eagleton sees the history of the modern age as a search for a viceroy for God. But this search, and the problem that gave rise to it, are part of a deeper history that sometimes comes to the surface in his account. The modern age is defined by the rise of science and the split it caused between a material world determined by the laws of nature and qualities we associate with mind and spirit: thought, free will, value and spirituality. Reconciling spirit and matter, determinism and free will, or reducing one to the other, has been the principal task of modern philosophy and theology. Eliminating or reconfiguring God is just part of that job.

Eagleton’s approach to modern history is influenced by his background in literature and cultural studies. His interest is not so much in philosophical and theological theories as in their relation to society and culture. This causes him to misread the intent of some of the thinkers he discusses. They were not, for the most part, in the business of providing a substitute for all of the things that religion has done. Nor were they trying to sell a doctrine to uneducated people. But he is right to emphasise that religion has played an important role in Western societies and that its influence is by no means a thing of the past. His perspective makes him one of the most interesting of recent writers who have turned their attention to a phenomenon that many secular thinkers would prefer to ignore: the persistence of religious ideas in political life and culture. •

Culture and the Death of God

By Terry Eagleton | Yale University Press | $34.95