If you ask the Greens, Higgins is officially in play. The inner-eastern Melbourne seat held since 2009 by assistant treasurer Kelly O’Dwyer is blue-ribbon Liberal heartland. A reliable contributor to the party since its creation in 1949, the seat has hosted two Liberal prime ministers, Harold Holt and John Gorton, as well as Australia’s longest-serving treasurer, Peter Costello. So safe has the seat been that Liberal candidates have never had to rely on preferences to win, though O’Dwyer came closest in 2010 with a primary vote of 51.7 per cent, the lowest on record.

Recent polling suggests a different scenario this time around. A Lonergan Research survey commissioned by the Greens suggests that O’Dwyer’s primary vote has plunged from 54.4 per cent in 2013 to “just” 44.1 per cent, with the Greens sneaking into second place, at 24.1 per cent, ahead of Labor’s 18.5 per cent. With Labor and minor-party preferences favouring the Greens almost three to one, the poll estimates a two-candidate-preferred result of 53 per cent to the Liberals, down from 59.9 per cent at the 2013 federal election.

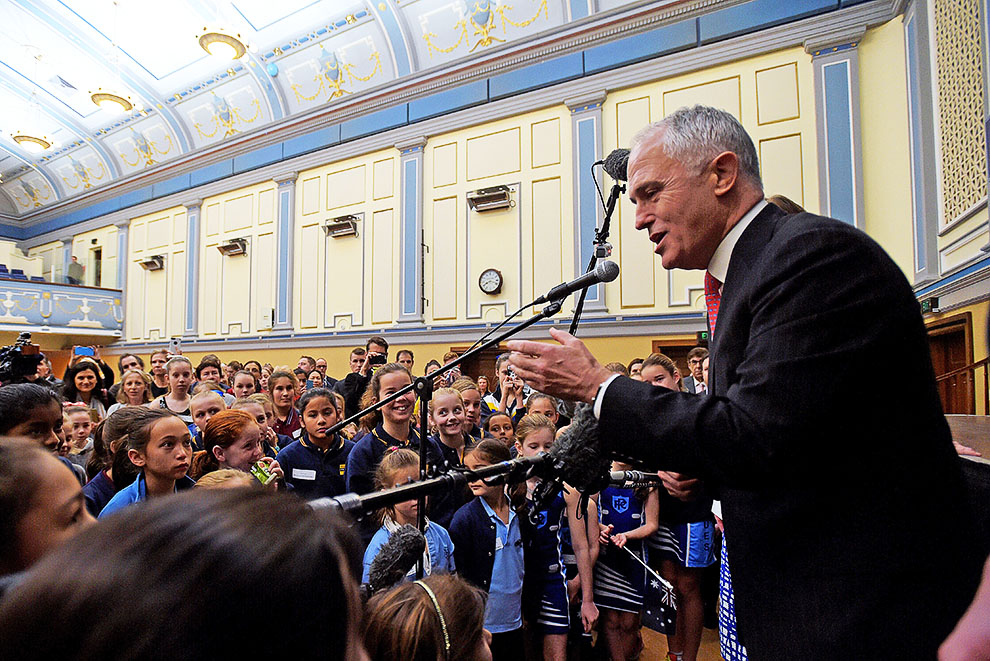

Although that would still mean a comfortable win, if technically marginal, the Greens had previously targeted the seat as winnable and are reportedly sufficiently emboldened to be transferring resources for a concerted push behind their high-profile candidate Jason Ball. And the Liberals are clearly concerned; last week Malcolm Turnbull took time out of his campaigning to join O’Dwyer in announcing funding for some local netball courts – the sort of job that would be left to the local member in more comfortable times.

As potentially the first federal Liberal seat to fall to the Greens, Higgins is a tempting prize, and this is not the first time the Greens have dared to dream. At the 2009 by-election triggered by Peter Costello’s retirement, Labor decided not to stand a candidate; by-elections tend to swing against sitting governments, so this decision suited the risk-averse Rudd government to a tee. The Greens were left as the sole realistic challenger and, sensing an opportunity, stood high-profile (read: controversial) Canberra academic Clive Hamilton.

Though he achieved the party’s then highest federal primary vote of 32.4 per cent, Hamilton was not as successful as had been hoped. The Greens fell well short of their aim of taking the seat to preferences, and O’Dwyer won a higher primary and two-candidate-preferred vote than Costello had achieved in 2007. Crucially, Hamilton failed to attract the support of a significant proportion of 2007 Labor voters. While the available data is limited, estimates suggest that at least 30 per cent of Labor supporters voted ultimately for the Liberal candidate, with an additional 20 per cent abstaining.

This split reflects the demography of Labor support, a reality particularly well illustrated in a seat like Higgins. Alongside the strongly Liberal core, the seat hosts two separate pockets of non-Liberal support. The northwest overlaps with the state electoral district of Prahran, where a young and highly educated population has produced a modern twist on the bellwether seat. Long alternating between Labor and Liberal members, at the 2014 Victorian state election the Greens targeted Prahran, turning sufficient Labor voters to nudge into second place and secure victory over the Liberals on Labor preferences – received at a rate approaching 90 per cent.

But Prahran doesn’t reflect the entirety of Labor’s support in Higgins. The southeast of the seat, overlapping the state seat of Oakleigh, is a more traditional Labor constituency. Oakleigh, ironclad Labor territory, was won with a 58–42 margin at the 2014 state election, and returned a Greens vote of just 13 per cent. At the 2009 federal by-election, these voters proved more reluctant to transfer their support to the Greens; in the southeast, the Liberal two-candidate-preferred vote rose by 5.9 per cent, against 2.6 per cent in the northwest. In a sense, this dynamic reflects both the electoral challenges facing modern Labor and the current limits to the Greens’ growth.

Labor’s broad constituency is a legacy of Gough Whitlam, its leader for a decade from 1967. Recognising the limits of a party built solely on organised labour and the working-class vote, Whitlam attracted a new demographic of tertiary-educated voters with policies such as free higher education and a stronger focus on women. As Labor struggles to find a raison d’être in the modern political landscape, one of the Greens’ great successes has been to build on the party’s founding “dark green” environmentalists and detach significant portions of the Whitlam demographic from Labor – with a little help from the rise and implosion of the Australian Democrats.

Even more important, though, is the Greens’ growing traction with young voters, for many of whom the major parties offer no attractive vision. As many as 30 per cent of voters aged eighteen to twenty-four and 25 per cent of those aged eighteen to thirty-four vote Green, against a 2013 national average of less than 9 per cent, and many will never have voted otherwise. In another era these would have been Whitlam Laborites. Party loyalty, though declining, remains a powerful factor, and in this demographic the Greens have the makings of an electoral base. But the fact that the Greens vote is so concentrated in this core demographic indicates the party’s limits. For the foreseeable future, their electoral prospects are restricted to those inner-city electorates where the concentration of young and highly educated voters is sufficient – Melbourne and Grayndler, and maybe Batman, Wills or even Higgins.

So what would it take for a historic victory in Kelly O’Dwyer’s seat? The arithmetic is simple enough. The Greens either need to finish ahead of Labor, or close enough that minor-party preferences nudge them into second place. The Liberals also need to poll poorly enough to stand a chance of being overhauled. While Labor voters seem happier to preference the Greens than to transfer their vote in the absence of a Labor candidate, the Greens cannot count on the level of support enjoyed in Prahran across the rest of the seat. And while a range of minor players have joined Labor in recommending their voters preference the Greens, directing preferences is a cat-herding exercise at the best of times, particularly without the boots on the ground that come with an established party organisation. Without being privy to the full polling data, it seems reasonable to assume that around 80 per cent of Labor supporters and 60 per cent of other voters will preference the Greens. On those numbers, the Liberal primary vote would need to drop to an unheard-of 41 per cent.

While this is likely to prove too big a hurdle for the Greens, that there is a contest at all is a sign of the times. The major parties have “hollowed out” and lost their connection to society, and are struggling to find meaning and maintain relevance in a changing world, but the Greens boast a healthy membership and are undergoing an evolution. At the 2013 federal election the overall Greens vote fell, with their appeal as a protest option deflating in light of the 2010–13 parliamentary politicking, and alternative options abounding. Yet their vote in capital cities increased, and Adam Bandt not only held Melbourne but increased his majority – clear signs of a core constituency entrenching itself. Though Higgins looks a bridge too far this time, the Greens are on the march, and the Liberals are right to be concerned. •