Part of our collection of articles on Australian history’s missing women, in collaboration with the Australian Dictionary of Biography

Born in a remote mining town at the dawn of the last century, Jessie Miller used her intelligence, passion and courage to achieve worldwide fame as a record-setting aviatrix.

Miller was born Jessie Maude Beveridge in Southern Cross, 371 kilometres east of Perth, where her father Charles Beveridge was the bank manager. Her childhood nickname, “Chubbie,” stuck with her throughout her life, an ironic nod to her slight frame. Her mother Maude gave birth to two more children: Eleanor (1902), who did not survive her first year, and Thomas (1905).

Charles Beveridge’s banking career took them to Perth, Broken Hill, Timaru (New Zealand) and then Melbourne. A religious family, they spent much time reading the Bible and attending church. Miller showed great musical talent as a child and considered a career as a concert pianist. She was also a talented athlete.

Not long after she turned eighteen, Jessie married twenty-three-year-old journalist Keith Miller. She soon gave birth to a premature baby who survived only a few hours, and subsequently miscarried twice. As she later commented, she and Keith were ill matched, and the marriage soon foundered. “It was like two babies getting married,” she said. “Our characters were poles apart.” Keith had “home and fireside” ideas; she chose adventure and “demanded the right to live my own life.” They would remain good friends.

Her father died in 1925 and her adored brother Tommy, aged twenty-two, in 1927. To assuage her grief — and escape her marriage — she decided to visit her father’s family in England. She sold carpet-sweepers door-to-door to raise funds for the trip, succeeding with her cheerful, charming nature and broad smile.

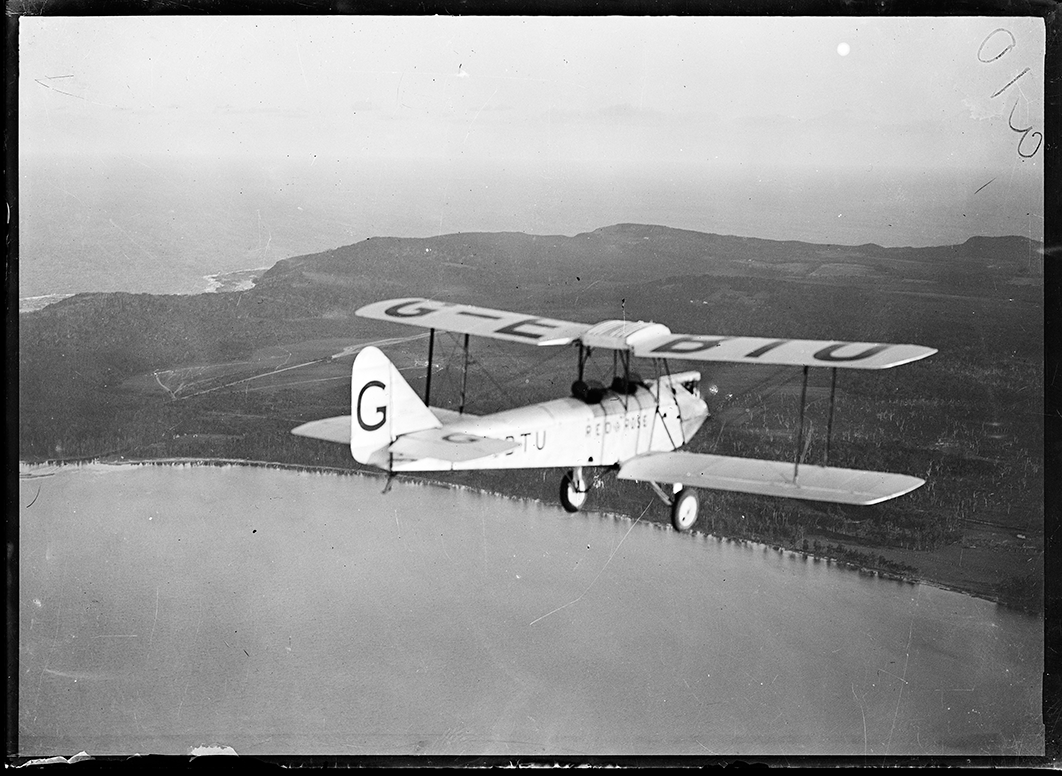

At a party in London Miller met first world war veteran Bill Lancaster, who was planning a record-making flight from England to Australia. Because the skies were largely unregulated, the 1920s and 30s were a golden period for female pilots. If a woman had money and daring, she could fly where no one had flown before, setting records and gaining fame and fortune. With no previous flying experience, the enterprising Miller convinced the poorly organised Lancaster to take her on the 22,000-kilometre trip as his passenger in an Avro Avian biplane. He agreed, provided Miller could raise the money and deal with the administrative details, which she duly did.

Vivacious, dynamic Miller became the first woman to fly from England to Australia as passenger, the first to fly more than 8000 miles (almost 13,000 kilometres), the first woman to cross the equator in a plane to the southern hemisphere, and the first woman to fly from north to south over the Australian continent. She learned to fly and to service the plane on the journey, during which she and Lancaster fell in love. Among her challenges were a forced landing at the Burmese capital of Rangoon (now Yangon, in Myanmar), a deadly serpent to dispatch from the cockpit, and a crash-landing in Indonesia. Miller and Lancaster were both slightly injured in the latter incident and had to wait on repairs in Singapore. Although they had failed in their bid, Miller was dubbed the first “international aviatrix” of the southern hemisphere.

Miller then accepted an offer to fly planes for Hollywood movies. When this fell through, she studied to be a radio operator and gained her US private pilot’s licence in 1929. She was the only antipodean to compete in the 1929 Women’s Air Derby (the “Powder Puff Derby”), a 4500-kilometre race from Santa Monica, California to Cleveland, Ohio. She won third place in the light plane division, then came equal first in the Cleveland air races in her first closed-circuit pylon race. She was a founding member of the Ninety-Nines, an international organisation for female pilots.

W.N. Lancaster and Jessie Miller’s aeroplane, the Red Rose, flying over the coast of New South Wales, c. 1928. Fairfax Collection, National Library of Australia, 6334974.

Seemingly indefatigable, she competed in the Ford Reliability Tou,r, a journey to thirty-two North American cities, and then became a test pilot for the Victor Aircraft Company. She was the first woman to earn a commercial pilot’s licence in Canada, and was hired as a demonstration pilot for the C.T. Stork Corporation. In 1930 she broke the US transcontinental air-speed record, and soon after was the first woman to fly from Florida to Cuba. On her return trip she flew off course, became stranded on a remote island for four days and was presumed dead. She was eventually rescued by an Australian sailor.

Miller undertook many speaking engagements during these years, urging the advancement of women in aviation and all other areas of life. She once demanded of a reporter, “Please don’t ask me the bunk [such as], ‘Do you like babies? Do you cook? Do you admire the American housewife?’”

Keith Miller requested a divorce in 1931. The following year, Jessie Miller and Lancaster moved to Miami and were hired to fly for Latin American Airways. Miller had found a ghostwriter, Charles Haden Clarke, to help with a planned autobiography, and he moved into their cottage. Miller began drinking heavily, frustrated and disillusioned with Lancaster, who seemed unlikely ever to divorce his Catholic wife. While he was away flying, Miller and Clarke fell in love and decided to marry.

One night after Lancaster’s return, Clarke was shot in the head with Lancaster’s gun. Having confessed to forging Clarke’s two suicide notes, Lancaster was charged with murder. Although he was acquitted after a sensational court case, suspicion hung over him. Even Miller remained unsure about what had really happened.

Miller returned to England, where she concentrated on writing her autobiography. Lancaster, unable to find work, decided to try to set a new record flying from Croydon to Cape Town, both to recapture Miller’s affection and to restore his own reputation. His preparations were said to be careless and his funds very low. Over the Sahara on a moonless night, he flew off course and crash-landed. Miller had told him she would search for him if he went missing, and tried unavailingly to borrow a search plane. She held onto hope as long as she could, feeling partly responsible for Lancaster’s actions. It was not until twenty-nine years later, in 1962, that his body was found beside his wrecked plane.

Finding the funds for flying adventures became increasingly difficult in the depressed economy of the 1930s. This especially affected female pilots like Miller, who failed to acquire the finance she needed to take part in the 1934 Centenary Air Race from London to Melbourne. She obtained work preparing aerial survey maps of West Africa, and made plans for another record flight from London down the coast of West Africa to Cape Town, supporting the autogyro flight of Mary Bruce, but this trip was ultimately cancelled. She then planned to establish a commercial travelling business carrying samples of goods from England to trading outposts in Africa, as far south as Cape Town, taking orders on the way. But this enterprise was foiled by an accident in Abomey-Calavi, Benin, that damaged her Robinson Redwing plane beyond repair.

Now heavily in debt, she returned to England and worked as manager at the Commercial Air Hire Company, owned by Mary Bruce and Irish pilot Johnnie Pugh, a decorated RAF officer. Miller married Pugh in 1936, moving with him to Singapore and Spain, and then back to London.

Jessie Miller may have started out as an unconventional young woman seeking adventure, but she became a complex, thoughtful achiever. As her adventures turned dangerous and tragic, her thrillseeking transformed into resourcefulness, bravery, composure and a determination to be happy. “Life at its best is short anyway so I guess I have no complaint coming,” she said. She died in 1972, never having returned to Australia. •

Further reading

The Fabulous Flying Mrs Miller: An Australian’s True Story of Adventure, Danger, Romance and Murder, by Carol Baxter, Allen & Unwin, 2017

The Flying Adventures of Jessie Keith “Chubbie” Miller: The Southern Hemisphere’s First International Aviatrix, by Chrystopher J. Spicer, McFarland & Company, 2017

Verdict on a Lost Flyer: The Story of Bill Lancaster and Chubbie Miller, by Ralph Barker, Fontana, 1986