ON THE first weekend in July, Brisbane’s Cultural Centre was given over to what was called a “Celebration” of Torres Strait Islander culture. The day before, in the Anglican Cathedral, Islanders had commemorated the “Coming of the Light,” 1 July 1871 being the date when Christianity came to Torres Strait. The next day crowds came to look at the display of Islander art under the title, Land Sea and Sky, occupying a whole floor of the Gallery of Modern Art, some exquisite paintings of fish and birds at the State Library, and yet another display of nineteenth-century artefacts in the Museum beyond. Through Saturday and Sunday Islander dancers and singers performed in the open space between the Library and GOMA, and a long queue formed to taste Islander food, cooked in an earth oven. The dancing and food were only for the one weekend, but the exhibitions run until October, a remarkable collaboration between the three institutions, who have also produced a lavish catalogue, entitled The Torres Strait Islands.

The Torres Strait Islanders are Australia’s other indigenous people. Though often bundled together with the more numerous Aborigines in official reports and politically correct speeches, they and their history are different in various ways. They have been classified as Melanesians, but just as in the old days their islands, scattered through the waters between Cape York and Papua, mediated ideas from the two mainlands, so the influences they have been exposed to over the 200 years of European contact have been absorbed and integrated in a culture that is dynamic and outward looking. They have been ready to take up and make their own new styles and ideas, not just the missionaries’ Christianity, but in music and dance, and cuisine, not just from Anglo-Australia but also from the various Pacific Islanders and Asians who passed through the strait in the nineteenth century, often staying and marrying Islander women.

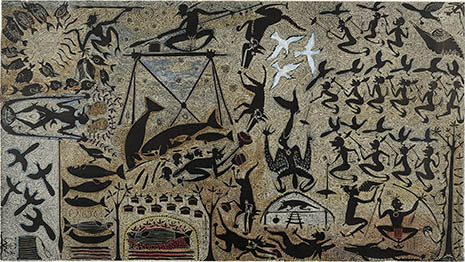

In the old days, Islander creativity seems to have been mainly expressed in dance and ceremony, with elaborate headdresses, and masks made from turtle shell or wood. Some antique examples of these are to be seen in the museum, some from its vaults and some brought out from the Cambridge Museum (along with their curator, Dr Anita Herle). The halo-shaped feather headdress, called the dari, has become the Islander flag and emblem. The graphic arts were less developed, but it has been in this form that the new generation of Islander artists have gained attention. Dennis Nona, one of the first to be exhibited in the southern cities, began with linocuts densely filled with figures – humans, birds and fish – in what seems like continuous motion. Currently exhibiting in Paris, in this exhibition he is represented by several bronze sculptures, including a stunning figure of a man astride a crocodile. Alick Tipoti, whose linocuts stand out among a profusion of such works, has a mural running the length of the GOMA floor.

Ken Thaiday Snr produces sculptures of a different kind, drawing inspiration from the headdresses the old people used for dances and ceremonies to create fantastic objects incorporating birds and fish, with bird down representing sea foam. Brian Robinson displays two crabs, made out of formex and lace. In a similar way, Jenny and Charlotte Mye have transformed the plain pandanus baskets used by their mothers to carry food from the gardens, using instead brilliantly coloured polypropylene tapes, which originally came to their island as binding for packing cases.

The story is similar with the dances performed over the weekend. The old style of dance, in which the performers wear the prototypic dari feather headdress, could be seen, but the “Island Dance” which is mostly performed is an adaptation of a South Sea style devised around the turn of last century. The music accompanying “Island Dance” is similarly derived from the Pacific, though for the disco style of dancing the new generation of composers use guitars and a reggae beat. A choir of around 100 voices sang Islander hymns on Sunday evening.

The thematic emphasis of these Islander creations is on “culture” – on what makes Torres Strait and its people distinctive, such as dancing, hunting turtle and dugong, fishing, or the great outrigger canoes that carried their forefathers on trading and raiding expeditions. Members of this rising generation of artists draw on the memories of their parents and grandparents, and consult the writings of anthropologists and folklorists for myths and weather lore that might have been forgotten as modernity penetrated the islands. What is presented as “Islander culture” focuses on some thirteen long-established communities scattered on islands throughout the Strait.

Thursday Island has been the commercial and administrative centre since 1879. But where once TI anchorage was thronged with pearling luggers, it is rare to see one now. Some Islanders are involved in commercial fishing, but the economy is driven by government, with something like a score of departments represented. On the outer islands it is possible to eke out a living from hunting and fishing, underwritten by welfare to meet cash needs. But the great majority of Islanders now live on mainland Australia.

Islanders seem to differ from Aborigines in being more ready to relocate. When the pearling industry failed in the early 1960s they began moving south, particularly to Queensland, where their labour was in high demand on the cane fields and the railways. These occupations enabled them to settle, before mechanisation sent the younger generation to look for other kinds of work. Now living on the mainland for more than a generation, they have adapted their way of life. Obviously they are no longer able to hunt turtle and dugong, but they have been able to transplant elements of their culture, particularly feasting to celebrate important occasions, religious and familial. Various towns along the Queensland coast, including Brisbane, have associations that sponsor “Islander” activities such as dance and craft.

The hundreds if not thousands of Queenslanders who visited the exhibitions and watched the dancing over that weekend will have come away with a strong sense of the Islander presence and perhaps also of their distinctiveness as an Australian indigenous people. “Culture,” after all, is what has established Aborigines as a positive value in the consciousness of settler Australians; this Celebration should have done the same for the Torres Strait Islanders.

And what of the Islanders themselves, many of whom were also at the Celebration, as spectators as well as performers – particularly the young ones who have grown up on the mainland? I can do no better than quote the words of an Islander academic, Leah Lui-Chivizhe, who writes, “I think the weekend nourished the cultural souls of many Islanders (it did for me), strengthening Islanders from the inside for their continuing journey that is of necessity outward and forward looking, yet anchored strongly to a rich cultural past.” •