If you’re in a gloomy mood, the Bureau of Statistics won’t be helping to pull you out of it. First it told us that wages across Australia grew at their lowest level on record, just 1.9 per cent, in the year to September. Now it tells us that, despite that unprecedented restraint, a net 70,000 full-time jobs were wiped out in the first ten months of 2016.

At first sight, these figures provide strong evidence that Australia’s economy is weakening, despite the welcome 3.1 per cent growth in the trend level of output (gross domestic product) over the year to June. But bear in mind that statistics are not the facts we sometimes take them for. They are either informed estimates, or survey data – and both are fallible. We’ll come back to this point later.

The figures certainly add to the signals troubling policy-makers. Growth in business credit has slowed sharply; indeed, business credit has grown just 0.6 per cent over the past five months, implying that business confidence is low. Retail sales volumes are up by just 0.2 per cent over the past six months, implying that consumer confidence is low.

Housing approvals are falling, admittedly from record levels. And while business investment (other than mining) is growing, and government investment is finally climbing off the floor, their combined impact is far outweighed by the massive decline in mining investment.

Moreover, despite the Reserve Bank’s efforts to drive the dollar down, it is higher now than it was a year ago, cutting off the gains we anticipated for exporters and import-competing industries, from education and tourism to manufacturing and agriculture.

If you want to be despondent, you could add the fact that the two big uncertainties over the Australian economy – the risk of a hard landing from China’s housing bubble, and the not-unrelated risk of a crash in our own hyperinflated property market – have now been joined by a third big uncertainty: what will be the global economic impact of President Trump? Despite ridiculous claims from both sides, it will be another year, maybe much more, before we know the answer to that.

So it’s not surprising that International Monetary Fund staff this week cautioned the federal government against cutting the budget deficit too fast, and urged it to focus instead on building new infrastructure. Or that the Reserve Bank has felt desperate enough to cut interest rates twice since May, despite the evidence suggesting that the cuts are doing more to boost housing prices than growth and jobs.

For the last four years, since the mining investment boom peaked unexpectedly early, around the middle of 2012, the key risk facing the nation has been that mining investment will deflate even faster in a bust than it builds up in a boom. In the past, every time mining investment has gone bust, the Australian economy has gone bust with it. The job of policy-makers has been to try to stimulate above-average growth in the non-mining economy, so that the mining bust doesn’t drag us into recession.

By and large, the progress score is: so far, so good. The economy has kept growing, partly because the Reserve Bank slashed interest rates to unprecedented lows to stimulate a real estate boom. Australian households have played their part, adding an extra $300 billion over the past three years to what is now one of the world’s heaviest debt burdens. And of course, despite its rhetoric, the federal government has left the budget deficit as it was, spending $1.09 for every $1 of revenue it earned in 2015–16, and keeping the deficit at $40 billion.

Jobs had also kept growing – until now. That’s the worry in the figures the Bureau of Statistics released yesterday. At face value, they imply that the jobs market has gone from very strong growth in 2015 to treading water at best, or going backwards at worst, in 2016.

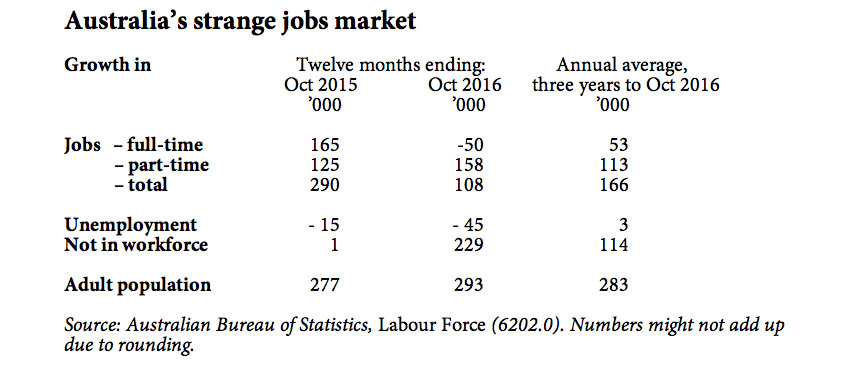

Taken literally, on the Bureau’s trend measure – which it urges us to use instead of the yo-yo seasonally adjusted measures preferred by bank analysts and the media – full-time jobs have fallen by 50,000 over the past twelve months, after growing by 165,000 in the previous twelve. Yet unemployment has kept falling, by 45,000 in the same year, shrinking the trend unemployment rate to 5.6 per cent in October.

Where have the workers gone? Out of the labour market. In the year to October 2016, the adult (fifteen and over) population of Australia grew by 293,000, but the number in the labour market grew by just 63,000. The rest joined the swelling ranks of those counted as “not in the labour force”: retirees, students, full-time mothers, and the ever-growing numbers of those whose lives have been too ruined by drugs, alcohol, injury, disability, personal struggles or mental illness to be able to find a job.

The collapse of full-time jobs began in January. The Bureau estimates that 70,000 full-time jobs have gone this year, mostly in New South Wales, Queensland and Western Australia. Victoria has been the standout defying the trend, but even there, on the new figures, full-time jobs peaked in August, and are now falling. They peaked in 2015 in New South Wales and Queensland, in 2014 in Western Australia and the Northern Territory – and in 2008 in South Australia and Tasmania. That picture is hard to ignore.

Yet be wary. The jobs figures come from a sample survey – a huge one, of 26,000 households, involving one in every 300 Australians – but even a huge survey can end up with an unrepresentative sample. And when our focus is not so much on the number of jobs as the change in them from month to month, the risk of the numbers painting the wrong picture is significant.

Just compare the past two years. Should we really believe that in 2015 job growth was so strong that it exceeded the growth in the adult population – whereas this year it has suddenly shrunk to a fraction of its previous level?

Should we really believe that Australia added a net 165,000 full-time jobs in the year to October 2015, then lost a net 50,000 in the year to October 2016? Does anyone believe that New South Wales added 133,500 full-time jobs in the first year, then lost 51,000 of them in the second?

Should we really believe that last year virtually all the growth in the adult population went into the labour force, whereas this year the vast bulk of it was outside the workforce?

The Bureau urges caution. It points out that, as a group, the new households surveyed in Queensland in the past two months have significantly lower employment rates – and particularly, full-time job rates – than the group of households that formed part of the previous numbers. It’s possible that the earlier numbers were too high, or the new ones are too low, or both.

Even at the national level, the households that will drop out of the survey next month had employment rates noticeably below the average of other months; there could well be a bounceback in the November figures, simply as a result of their leaving the survey.

It might be better to look at the two years together. In that time, the number of adult Australians has risen by 570,000, the number of full-time jobs by 115,000, the number of part-time jobs by 283,000, total employment by 398,000, and the numbers outside the workforce by 230,000. Unemployment is still down by 60,000, which is hard to explain. But taken together, the numbers for the two years tell a more plausible story than those for either year do by themselves.

The economy certainly appears to be slowing, and 2017 could be a harder year than this one. The combination of record household debt, low wage growth and a flat jobs market is an ominous one for consumer spending, which provides the bulk of economic activity. And, as the IMF team noted, the risks are weighted to the downside.

But whether those risks eventuate remains to be seen. Don’t take these jobs figures too literally. Don’t ignore our chances of muddling through yet again. •