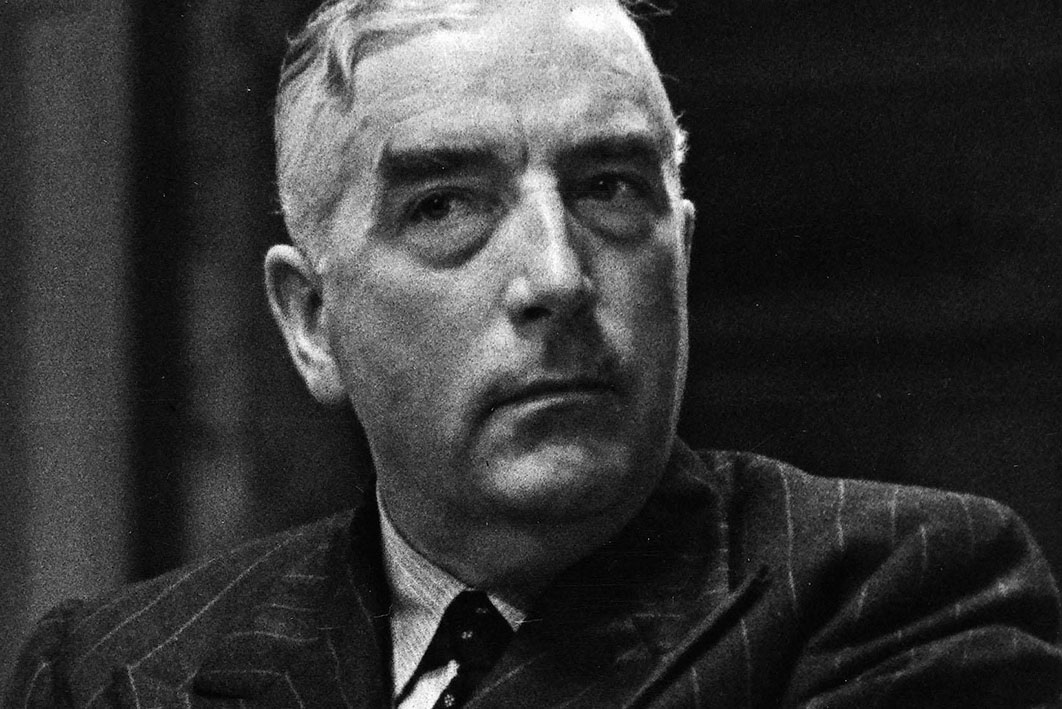

The Liberal Party federal council’s call to sell off the ABC is unlikely to be taken up by the parliamentary party, but the fact that it was made at all represents not only a major challenge to Malcolm Turnbull but also a break with the party’s own history. The prime minister is quite right to insist that policy remains the sole prerogative of the parliamentary party: the perfectly sound reasons why this is so were enunciated repeatedly by the party’s founder, Robert Menzies, during his long period in power.

Federal council members might consider the careful phrasing of the party website’s description of their role: “The federal council is responsible for the party’s federal constitution and federal platform. It is the organisational wing’s highest forum for debating federal policies. Views of the federal council are not binding on the parliamentary party, but do carry considerable weight as the stated position of the organisation on a range of policy issues.” Those who voted to privatise the ABC might believe they stuck to the letter of that description, but only if they ignore its cautious ambiguity.

Just how Turnbull manages the council’s incursion into policy will test his mettle. The council’s decision is a distraction he simply doesn’t need right now, and has handed the opposition a potentially powerful weapon. With the party growing ever more fractious, it raises again the question of how he can placate an increasingly conservative base.

The problem isn’t new. The Liberal Party’s predecessor, the United Australia Party — itself a hastily cobbled amalgam of the former Nationalist Party and a group of Labor defectors — arose in response to the crisis of the Great Depression and the inability of a deeply divided Labor government, under James Scullin, to respond effectively to its impact.

Pushing ideas of “sound finance” and government retrenchment, the UAP was organised more like a business than a political party. It was financed by business and largely controlled by business through extra-parliamentary committees that raised funds, selected candidates and dictated policy. Several Melbourne business figures played a key role in encouraging the popular Joseph Lyons to defect from the Labor Party, and he became prime minister after the defeat of the Scullin government.

Menzies, who had come to Canberra after a stellar career at the Melbourne bar and a stint in Victorian politics, had taken a keen interest in a national insurance scheme, and when prime minister Joseph Lyons abruptly postponed it in 1939, he resigned angrily from cabinet. Three weeks later Lyons died.

The reasons behind the decision to shelve the scheme have never been clear, but Menzies blamed the big insurance interests behind the UAP.

The lesson was not lost on him. After his first unhappy term as prime minister, when he succeeded Lyons only to resign amid party tensions in 1941, he saw the UAP disintegrate. As he plotted and planned in exile, his bold proposal for a new political party rested on the primacy of the parliamentary party over the organisational wing where policy was concerned.

In his long reign over the party, he never wavered on this principle. He had formidable clashes with organisational figures from time to time, but always insisted that while he would listen to policy advice, the ultimate decisions belonged to the elected MPs.

By the mid 1950s, half a decade into the party’s long postwar reign, the organisational wing was growing restive. It set up a research committee and a subcommittee of the federal council to investigate the relationship between the organisational and parliamentary wings, delivering a report in May 1956 entitled The Organisation’s Role and Status when in Government.

The party’s constitution had provided for a joint standing committee on federal policy, but the report complained of “a growing sense of frustration” that it “has virtually ceased to function since 1949.” (In fact, it had not even met.) It also noted that the two other organisational bodies — the federal council and federal executive — had repeatedly made suggestions and passed resolutions, but the government had largely ignored them. “To put it boldly,” it said, “the government has rarely accepted the advice of the organisation on policy matters, and rarely carried out recommendations and suggestions.”

The federal executive endorsed the report and sent it to Menzies, along with an accompanying letter from federal president William Anderson, who told the prime minister that supporters (meaning financial donors) were “frequently shocked” at the ignorance of those who sought their money and purported to represent them “and would be amazed at the lack of consultation existing within our party.” He sought a meeting with Menzies.

The prime minister had other things on his mind — the Olympic Games in Melbourne, the Soviet invasion of Hungary and the Suez crisis — and did not meet party officials until February 1957. Accompanied by senior ministers Bill McMahon and Philip McBride, he invited the officials to the cabinet room and heard them out. He didn’t flare up at incursions into the policy area, as he had in the past, but McMahon pointedly reminded members of the executive to confine any public statements to the existing party platform and curtly added that matters of policy were for the government alone to determine.

When officials complained that party supporters were not being given “that extra ounce of consideration” when they made representations to government, Menzies took a conciliatory tone, saying that rejection did not mean that the proposals themselves were not taken seriously.

After the meeting, little changed other than a revival of the joint standing committee, which two ministers attended, and the appointment of “liaison ministers” to the organisation. Things continued much the same as they had before, with the government now helpfully sending copies of all ministerial press releases to the Liberal Party secretariat.

The near-loss in 1961 brought new tensions. Anderson accused the government of “insolence of office,” claiming that if it had heeded advice from the organisation it would not have lost the support of key sections of the business community. He summarised the government’s attitude to the party as “we know best, little people.”

Two developments arose from this: a commitment from the government to listen more closely to business and, second, a demand (not a request) to take the views of the organisation more seriously. But there was resistance. Treasurer Harold Holt complained to Menzies that a number of the federal council’s resolutions took no account of financial implications. He proposed a review of the council and suggested that while it might offer a general view on political questions it should not generally become involved with particular issues or pieces of legislation.

A few years later, though, the party organisation, acting on behalf of the business community, flexed its muscles decisively when the government unveiled its promised legislation to deal with restrictive trade practices, condemning it as too harsh and going far beyond what was necessary. Much debate and protracted negotiation took place, and the version enacted in 1967 — by which time Menzies had retired — was a much-attenuated version.

That incident, over half a century ago, was the last major stoush between the party and a governing federal Liberal leadership. The fact that the federal council has now chosen to take a stand on as contentious an issue as the ownership of the ABC is evidence of a growing frustration within the party. The challenge for Malcolm Turnbull and his senior ministers is to defend their rightful prerogative on policy — or else the lessons of history and the work of Robert Menzies count for nothing. ●