In a few months, pandemic permitting, Karin Kaper and Dirk Szuszies’s recently completed feature-length documentary Walter Kaufmann: Welch ein Leben! (Walter Kaufmann: What a Life!) will hit cinemas in Germany. But its subject, a German with an Australian passport, won’t be there for the film’s opening night. He died in Berlin on 15 April.

Kaufmann had turned ninety-seven in January. Virtually anybody who reaches such a ripe old age has led a life worth making into a film — or writing about, for that matter. Kaufmann’s story, that of a refugee from Nazi Germany who became an Australian writer and then moved to the old East Germany, was particularly rich.

Any biography is shaped by the letters, diaries and other sources available to the biographer. In Kaufmann’s case, much could be made of the thick files created by the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation in the 1950s, and those of ASIO’s East German equivalent, the Stasi, between the 1950s and the 1980s.

Even more might be made of Kaufmann’s own writings, including at least a dozen books that could be classified as either autobiographical fiction or memoir. But the life depicted by oneself is not necessarily any more accurate than the life that can be winnowed from the observations of outsiders, who in Kaufmann’s case included spies and informers. And in a life spanning nearly ten decades, many aspects won’t have been recorded by other people or deemed worth remembering by the subject himself.

The omissions start with Kaufmann’s early life. He was born Jizchak Schmeidler (or perhaps Sally Jizchak Schmeidler) on 19 January 1924 in Berlin’s Scheunenviertel, a neighbourhood dominated by Jewish migrants from Eastern Europe. His mother Rachela, originally from Poland, was among them. Aged seventeen when Jizchak was born, she was working as a shop assistant at a department store. That’s all we know about her; when Jizchak was three, she gave him up for adoption. We can only guess why.

His new parents were a couple from far-flung Duisburg, a city in the Ruhr Valley in the west of Germany. His adoptive father, Sally Kaufmann, had fought and been decorated in the first world war and afterwards practised as a lawyer and notary. Sally’s wife Johanna had been to art school, but her dreams of becoming an artist remained unfulfilled. Jizchak had no siblings, but later in life speculated that he may have been adopted not because his adoptive parents were childless but because Sally was also his biological father. But we simply don’t know why and how young Jizchak and his mother entered the Kaufmanns’ lives.

Jizchak, who became Walter upon his adoption, grew up in a well-to-do bourgeois household. Like his biological mother, his adoptive parents were Jewish. The family observed the high holidays, young Walter was required to take Hebrew classes, and Sally for many years chaired Duisburg’s Jewish congregation. Like many German Jews, though, the Kaufmanns were not overly religious.

The anti-Semitism of the Nazis, which would have such an impact on Walter’s life, didn’t come out of nowhere. A pogrom had occurred in the Scheunenviertel only a couple of months before Walter was born there, with Jews assaulted (and one of them killed) and their businesses looted. But the systematic discrimination against Jews, and their exclusion from public life in Nazi Germany would have come as a shock to the Kaufmanns. In early November 1938, during the so-called Reichskristallnacht pogroms, Sally Kaufmann was taken for a time to the Dachau concentration camp and the Kaufmanns’ house was ransacked while Walter and his mother hid in the basement.

The violence convinced the Kaufmanns that Walter, at least, needed to be sent to safety, and in January 1939, on his fifteenth birthday, he left on a Kindertransport to England. There he attended the New Herrlingen boarding school in Faversham, Kent. In June 1940, when the Battle of Dunkirk forced the British government to prepare the country for a German invasion, sixteen-year-old Walter was among the many recently arrived “enemy aliens” to be arrested. Then, together with more than 2000 other German and Austrian refugees, he was sent to Australia on the infamous Dunera and interned in a camp in the western NSW town of Hay. Under “reason for internment,” the dossier created by the Australian military authorities stated incongruously: “Enemy Alien — Refugee from Nazi oppression.”

Released from Hay in March 1942, Kaufmann joined the Australian army — or rather, the 8th Employment Company, which provided an opportunity for “refugee aliens” to contribute to the war effort. Still with the army, he applied for an Australian entry permit for his parents; by then, however, they had been deported, first to the Theresienstadt concentration camp, and then to Auschwitz, where they were killed. They shared the fate of the hundreds of Jews from Duisburg who became the victims of Nazi persecution. (The letters Johanna and Sally Kaufmann wrote to their son in England and in Australia are about to be published as a book.)

In 1944 Kaufmann married Tasmanian-born Barbara Dyer, who was eleven years older than him. They had met while she was working as an officer for army intelligence — a job she lost because of the relationship. (Kaufmann may have been in the army, but he was still an alien from Germany.) He was naturalised after the war was over, in 1946.

Kaufmann had begun to write fiction, in English, while he was still with the army, and by the end of the war was already a published author. In 1944, his short story “The Simple Things” won him the first of many literary prizes. He joined the Melbourne Realist Writers Group, a group of left-wing authors, and became friends with Frank Hardy and David Martin, the latter himself a Jewish refugee who had fled Germany in 1934. Martin in particular encouraged him to write about his experiences in Nazi Germany.

Kaufmann’s first novel, Voices in the Storm, an account of anti-fascist resistance and the coming of age of a Jewish boy in Nazi Germany, was published in 1953 by the Australasian Book Company, which had been set up by a group of like-minded authors. He later recalled that he himself sold 2000 copies of the book by hawking it at wharfs, mines and other workplaces during fifteen-minute stop-work meetings.

While he continued to write, Kaufmann worked in a wide range of jobs, including as a wedding photographer and a seaman. In 1955, the Seamen’s Union sent him to the Fifth World Festival of Youth and Students in Warsaw. There he met an East German publisher who convinced him that his writings, including Voices in the Storm, would find a receptive audience in communist East Germany — the German Democratic Republic, to give it its formal name, or GDR. Travelling from Warsaw to Berlin, he not only met fellow writers at a GDR writers’ congress, but also searched unsuccessfully for his biological mother.

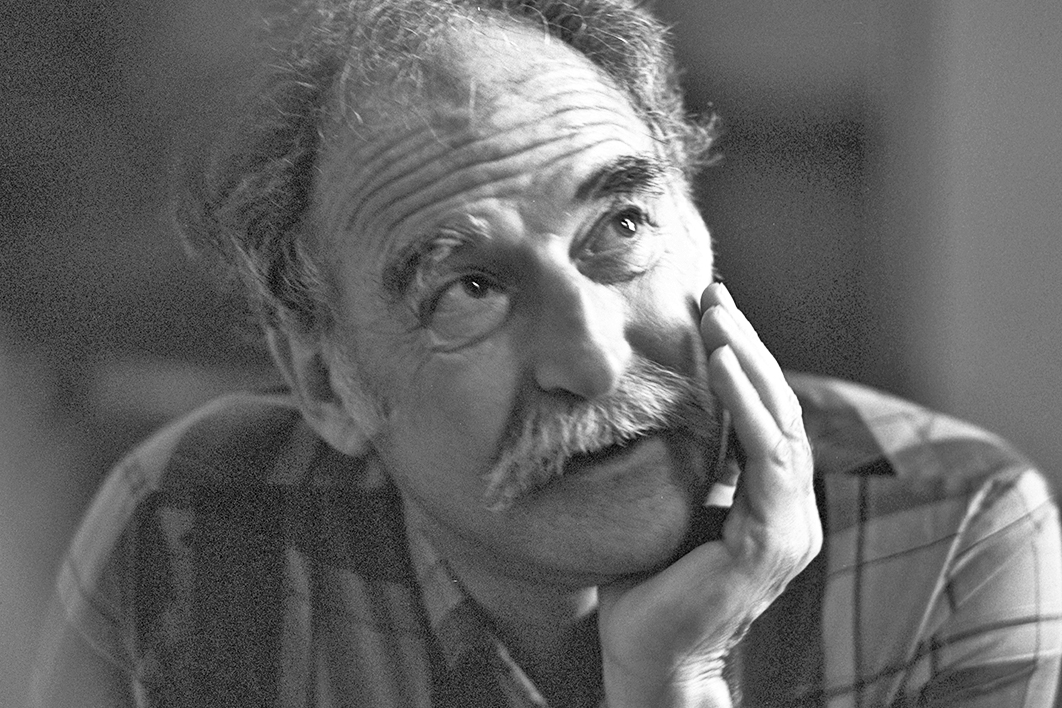

Walter Kaufmann (third from left, standing) with other members of the Australian delegation to the World Festival of Youth and Students in Warsaw in 1955. National Archives of Australia

Kaufmann found himself attracted to the prospect of becoming a writer in a country where people tried to live according to the philosophy he and his Australian comrades were preaching. For the first time since 1939, a return to Germany presented itself as an option. But first he went back to Australia as an attaché with the German team that attended the Melbourne Olympic Games.

After a lecture tour in which Kaufmann talked about his European travels (which had also led him to the Soviet Union), he and his wife moved to East Germany — or, in his words, he “returned home to foreign parts.” Unlike another Australian who migrated to East Germany at around the same time, the anthropologist Fred Rose, Kaufmann didn’t leave Australia because he felt victimised for his political convictions. (All he shared with Rose was a tendency to philander.)

The secretary of the GDR writers’ association had told him that he could be more useful in the West than in the East, but a short visit to his home town on his first trip back to Europe had convinced him that he wasn’t welcome there. His parents’ house was now occupied by strangers who did not even ask him inside.

By the time he arrived in East Berlin, however, the deal that had initially attracted him to East Germany had fallen through. The East German authorities deemed parts of the plot of Voices in the Storm to be against the party line and demanded that he rewrite the book. Kaufmann refused. But he used some of the autobiographical material that informed his first novel to write another book, which was allowed to be published. And despite this early setback, he could be a professional writer in the GDR, something that would not have been possible in Australia.

Back in Australia, Kaufmann had been a member of the Communist Party, but he later recalled neither wanting nor being able to join East Germany’s Socialist Unity Party. One prerequisite would have been taking out GDR citizenship, which he declined to do. Retaining his Australian citizenship meant he could travel the world.

And he did: to Western Europe, Asia and the Americas, including several times to the United States. As a roving reporter, he covered the Cuban revolution and the court case against the American civil rights activist Angela Davis in the early 1970s. His journeying provided him with the material that helped him become arguably East Germany’s most widely read travel writer.

Much of his writing about foreign places is reportage in the tradition of the “racing reporter” of the 1920s and 1930s, Egon Erwin Kisch. Although probably not as accomplished a writer as Kisch, Kaufmann too married social critique with travelogues. And his occupation as a travel writer and foreign correspondent at large was also an opportunity to escape, albeit only temporarily, the confines of East Germany’s insularity. He let his readers share in these escapes, and they loved him for it.

He also wrote short stories, novels and books for children. By the time the Berlin Wall came down, Kaufmann had published twenty-six books in German and was part of the country’s literary establishment. His standing is evident in the fact that in 1984 he was able to publish Flucht, a book about a medical doctor who left the GDR for West Germany.

When all his publishers went out of business after reunification, the sixty-six-year-old Kaufmann began a new career, as a German, rather than an East German, writer. He must also have realised that he had to move on from the travel writing that had made him a household name; with air travel now possible and affordable, his readers no longer needed the window on the world that he had been able to provide.

Much of Kaufmann’s post-1990 writing is autobiographical. There was a market for that too, but he didn’t enjoy the same success that had marked his career in the GDR. And although he began to publish books with West German publishers, he also contributed regularly to two daily newspapers that have acted as reminders of a bygone era, and of a state that ceased to exist in 1990: the Neues Deutschland, formerly the paper of the Socialist Unity Party, and the Junge Welt, which used to be published by the Free German Youth, the GDR’s official youth organisation. Kaufmann’s last Junge Welt article, a review of a book of poems by another nonagenarian, the East German writer Gisela Steineckert, appeared about a month before his death.

Kaufmann had felt less at home in the GDR than in Australia. But, he told an interviewer, the GDR “became my home when it had gone.” He reasoned that this was because he felt he had been taken care of there, both as a person and as a writer.

A Jew in Nazi Germany, an enemy alien in wartime England, a communist in Robert Menzies’s Australia, an Australian in East Germany, and somebody with a GDR identity in the reunified Germany: throughout his life, Kaufmann didn’t quite belong. Sometimes that was because he had been excluded; at other times, it was because he cultivated the sense of detachment that also characterises some of his writing.

For most of his life in East Germany, he wasn’t a foreigner just because of his Australian passport. Initially, he even spoke German with an Australian accent. And he continued to write in English. All the books he published in his first twenty years in Germany had to be translated. The way he tells the story, he eventually taught himself to write in German after a Melbourne publisher reissued Voices in the Storm in the early 1970s. When he took the opportunity to submit the book again for publication in the GDR, the text was approved without changes — with the proviso that it be translated by the author himself. Stimmen im Sturm, published in 1977, thus became the first book he wrote in German. He recalled that it was hard work to turn his English prose into German, but by the end of it, he had graduated from a German writer of English to a writer of German.

His German writing retained an Australian touch, though. He privileged unadorned and succinct prose, and an uncomplicated syntax. “My German has become like English,” he told an interviewer.

Three of his books were published in English by an East German publisher, but Voices in the Storm remained the only one of his books to be published in Australia. He may have identified as an Australian writer for much of his life, but the Australian reading public didn’t warm to him, despite his writing frequently about Australian topics, such as the Maralinga atomic tests, and despite much of his autobiographical fiction being set in Australia. I hope that Australians will one day discover one of their own — although in order to do so, they might have to rely on translations, as he wrote some of his more interesting autobiographical prose in German.

Biographies are not only shaped by the material on which a biographer can draw; they are also informed by broader narratives. The website advertising the forthcoming film about Kaufmann, for example, says, “For us filmmakers, this is the main content of Walter Kaufmann’s life: the catastrophic consequences of National Socialism; the legendary trial of Angela Davis; the revolution in Cuba; the discussion about Stalinism; the impact of the atomic bomb in Japan; the never-ending history of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict; the collapse of the GDR; the return of nationalist, anti-Semitic tendencies in Germany.” It’s not hard to anticipate the film’s drift.

Often biographies try to fit the life of an individual into a national story, or relate it to the life of a more famous person. That’s what happened to Kaufmann; in Germany he will also be remembered as the man who — albeit unwittingly and indirectly — ruined the reputation of East Germany’s most famous writer, and arguably its best, Christa Wolf.

Like Fred Rose, Kaufmann was a communist and therefore a person of interest to ASIO. Unlike Rose, Kaufmann did not become a spy himself when he moved to East Germany. On the contrary, the East German Stasi was as interested in Kaufmann as ASIO had been. Although he had chosen life in the communist East over life in the capitalist West, Kaufmann was not trusted. For good reason: while he remained faithful to socialism, including the perverted variety practised in the GDR, blind conformism was not his thing.

In the 1990s, Kaufmann’s Stasi file became the subject of a German literary controversy when it was revealed that Wolf had been among those reporting to the Stasi about Kaufmann (and, to a lesser extent, others). She was pilloried in much of the German media, including in a damning piece in the magazine Spiegel, even though Kaufmann, to whom she apologised, took her side. He did that not only because her transgressions were comparatively minor, but also because he was not somebody to hold grudges. When asked eight years ago to sum up his life, he said, “Life has been good to me. I’m not a victim. And I don’t feel like a victim.”

In Australia, Kaufmann may be remembered in the context of the uplifting and decidedly patriotic Dunera story, not least because he didn’t identify as a victim there either. Like many of those who later became known as the Dunera Boys, Kaufmann was appalled by the treatment meted out to the internees aboard the British ship but remembered fondly his first encounters with Australian soldiers, who escorted him and his fellow inmates to an internment camp in Hay. (He recalled his first impressions of Australia and Australians in a piece of autobiographical fiction published in Meanjin in 1954.)

When he interviewed Kaufmann on Late Night Live in 2014, Phillip Adams marvelled at the Dunera Boys as “the most extraordinary refugees we received” and described their contribution to Australia as “beyond parallel.” Kaufmann happily played along, referring to his stint in Hay as the “formative time of my life.” •