Paddington: A History

Edited by Greg Young | The Paddington Society and NewSouth | $69.99 | 340 pages

It was an open-and-shut case: the street just had to be widened. Increasing car ownership and urban development in Sydney after the second world war meant that arterial roads had become inadequate for through traffic in 1969, especially after trams had been removed eight years earlier. So the Department of Main Roads announced large-scale widening of roads to accommodate cars driving through the inner-Sydney suburb of Paddington on their merry way further east.

Opposing the proposal to widen the suburb’s Jersey Road was a mainly middle-class group of people who had founded one of Sydney’s first resident action groups, the Paddington Society, in 1964. Remarkably, they were victorious and Jersey Road was saved, though the threats persisted. This book is a tribute to the society and to the beauty and distinctiveness of the suburb that it saved.

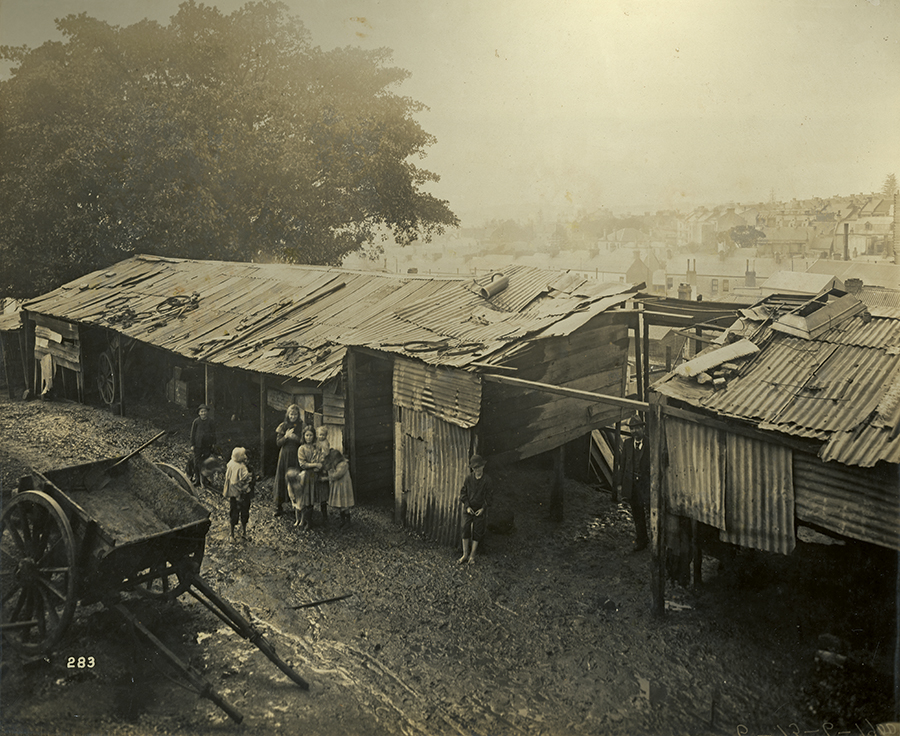

In the usually flat urban landscapes of suburban Australia, Paddington is a rare and exotic gem. Clustered in serried, bricked ranks around the hills close to the heart of Sydney, its Victorian and Edwardian housing survived early twentieth-century urban development because of its unfashionable working-class habitation. Backyards too small for playing cricket were unappealing to self-improving Sydneysiders, who preferred the greenfield developments on the ever-widening edges of the city. As the illustrations in this handsome book show, the result of Paddington’s complex history was a close-knit mix of terrace housing in a treeless setting that looked far from attractive in the 1950s and 60s, and ripe for gentrification.

Ably drawn together by Greg Young, this collection of essays fittingly commences with a study of the original owners of the place. The space between the sandy hilltop and the harbour was occupied by the Cadigal people, who fished in the streams and bay and lived in the wooded valleys. In “Aboriginal Paddington,” Paul Irish documents the tenacity of these Indigenous inhabitants in the face of the invaders’ expansion, which eventually forced them to move to La Perouse.

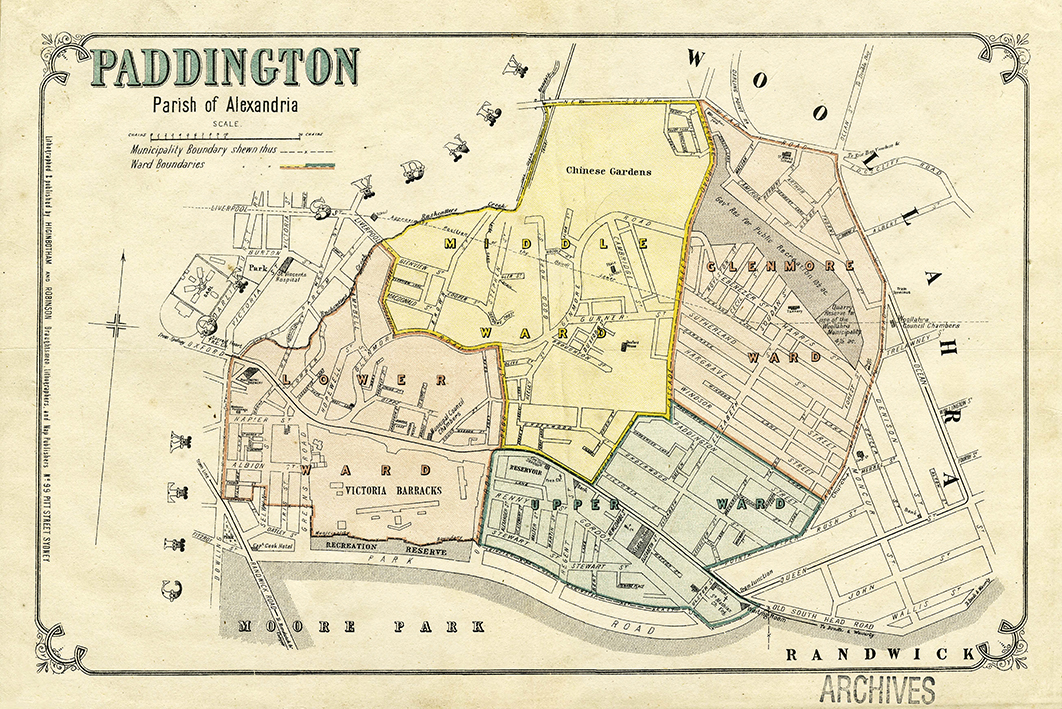

Paddington as depicted in the Atlas of the Suburbs of Sydney, 1886–88, prepared and published by Higinbotham & Robinson. National Library of Australia

After Bill Morrison’s scene-setting “Mapping Paddington,” succeeding chapters deal with aspects of Paddington history, illustrated with clear maps, lavish photographs (both historical and contemporary), architectural drawings and other artworks. In a lively overarching chapter, Garry Wotherspoon and Paul Ashton explain how the lack of a railway or wharfs meant that Paddington escaped industrialisation and “simply dozed in its dust between two world wars and into the 1950s”; and how, by 1966, the suburb enjoyed “a livelier and richer ambience” thanks to the one-third of its population who were of non-British origin.

In “Early Paddington,” Robert Griffin describes Governor Bourke’s vision of the area overlooking Rushcutters Bay as a suitable site for residences for government officials. A few of these early nineteenth-century villas remain, notably the house now known as Juniper Hall. The layout of these land grants would govern the shape of the present suburb. Another crucial factor in Paddington’s history was the selection of a site on the ridgeline, on sandy soil unsuitable for agriculture, for a new military establishment. Construction of Victoria Barracks began in 1841 and a village grew up nearby to house the workmen involved.

I particularly enjoyed and was enlightened by Griffin and Robert Brown’s chapter, “The Victorian Suburb,” which like other contributions to this book owes a well-acknowledged debt to Max Kelly’s pioneering Paddock Full of Houses (1978). Griffin and Brown explain how the mixture of street alignments, varying block depths and small-scale building construction resulted in a surprising variety of designs, avoiding the boring uniformity that might otherwise have emerged. In contrast to other suburbs, where building societies and large-scale developers financed long rows of identical terraces, in Paddington a builder of modest means “would complete one terrace house on his land then live in it while re-financing before completing others in the row.” By 1885 some 60 per cent of the suburb’s rental houses were owned by landlords whose holdings did not exceed four houses.

Stables at the rear of 30–32 Oxford Street, Paddington, on 17 July 1900. State Archives and Records New South Wales

Sharon Veale and Peter McNeil show how in Paddington, as elsewhere in Australian cities, a powerful shaping force has been gentrification after working-class tenanted properties fell into disrepair. “Between 1959 and 1966 nearly half of Paddington terraces changed hands,” they write, and new owners, including a number of influential gay men and women, shaped the terraces to their needs. One of the features to reappear was “Paddington lace” — as the photographs show clearly, the opening up of the closed-in balconies and the return of their cast-iron railings dramatically changed the visual appeal of the Victorian terraces. And the garden and street trees that appeared also enhanced the picturesque nature of the suburb.

A central and very readable chapter by Sheridan Burke, “Conserving Paddington,” tells the story of the creation of the Paddington Society in 1964 and its running battles with planners to save the fabric of the suburb. Burke shows how a vigorous and professional resident action group could prevail over the bureaucrats. Here and elsewhere, the book pays due credit to the individuals who launched the society, including writer Patricia Thompson and potter Marea Gazzard and their architect husbands John and Don. Sandra Hall’s chapter, “Bohemian Paddington,” peoples the book with some of the suburb’s resident counterculture inhabitants, and Peter McNeil introduces us to the creative men and women who made Paddington their home, including violin-maker Alfred Walter Heaps, poet Christopher Brennan, composer Peggy Glanville-Hicks and painters Margaret Olley, David Strachan, Donald Friend and many more. Viennese-born art dealer and bon vivant Rudy Komon opened his gallery in Paddington in 1959, and others soon followed, turning the area into a distinctive artistic hub.

In the final sections, Helen Armstrong’s “Changing Landscapes” shows us how Paddington looked over time, Peter Spearritt muses on the prospects for Paddington’s survival, and Robert Griffin provides an in-depth analysis of the varying forms of the suburb’s terrace housing over the period 1840–1910.

The structure of Paddington: A History inevitably results in some repetition. I also found the index disappointingly slim and was sorry to see that Walter Pulkownik, purveyor of Paddington Chocolates, was not mentioned. But these are minor criticisms of a handsome and worthwhile production. It is both an evocation of a much-loved Sydney suburb and an insight into the history of urban development in Australia. •