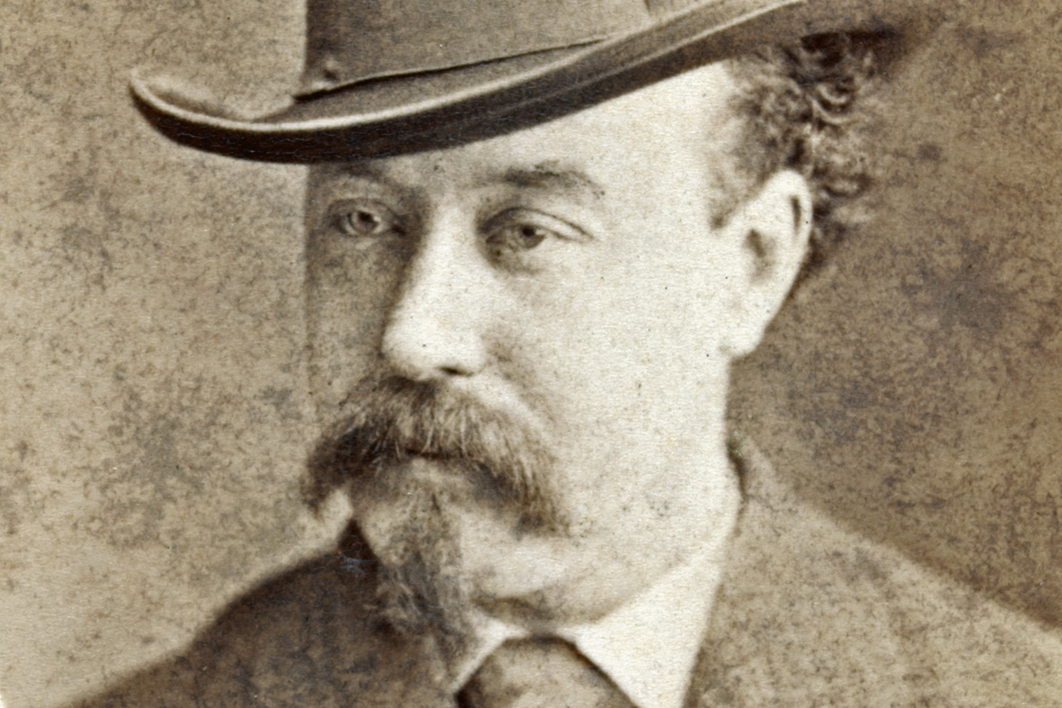

The life of one of Australia’s most controversial writers remained wrapped in mystery for more than a century after his death in 1896. John Stanley James, an English-born immigrant, became famous in Australia under double-blind pen-names, “the Vagabond” and “Julian Thomas.” His deception was so effective that he was even buried under a false name.

James was born in Walsall, Staffordshire, England, the only son of Joseph Green James (solicitor) and his wife Elizabeth (nee Stanley). In 1855, aged twelve, he ran away from his boarding school and began life as a vagabond with a band of gypsies. He returned home a few months later and become articled to his father as a law clerk.

Around 1862 he became involved with an Irish-born domestic servant named Mary Butler. When Mary became pregnant early in 1863, she was immediately sent to Australia to bear her child out of sight. Her son, born on 3 October 1863, came to be known by the made-up name of John Butler Cooper, later a noted Melbourne historian. The father’s name was not registered.

Throughout her subsequent life, Mary Butler remained close to the James family, usually living at the same address as members who had emigrated to Melbourne, and would late in life marry John James, an uncle of the Vagabond, whose property she eventually inherited. Ultimately they were buried in the same grave in St Kilda cemetery.

Back in 1862, after a heated argument with his father “over a lady,” James had moved to London, where he worked as a casual law clerk and freelance journalist. After a year of struggle, he found full-time work in 1863 with the London & North Western Railway, and was soon promoted to stationmaster at Nant y Bwch in Wales. Bored with this life, he left the railway in 1866 to pursue his interests in politics, labour issues and journalism.

In 1868 he spent some time in Dublin, Ireland, where the Fenian Brotherhood and the Irish Republican Brotherhood were agitating against British rule. In 1870 he went to Paris for the London Daily News and was imprisoned for six weeks as a suspected spy for the Communards. Freed after representations from the British embassy, he returned to England to write about agitation among rural workers for better wages.

In 1872 he emigrated to New York, describing his experiences as a steerage passenger for the London Daily News. After several assignments for the New York World, he was engaged by Joseph Arch as US representative of England’s National Agricultural Labourers’ Union, his task being to promote the migration of English labour and capital to the United States and Canada.

James returned temporarily to England in 1873, where he wrote articles describing the “Condition of the Working Classes of Great Britain,” which were later included in executive documents for the US Congress. During his time in Britain, he married Caroline Louisa Ashwood (nee Belliss), the well-off widow of a Shropshire farmer.

The couple soon sailed to the United States with her two young sons, arriving in New York in February 1875. The following month they bought ninety acres in Farmville, Virginia, which they called Stanley Park. They built a spacious timber mansion, which is preserved on a different site. There, James intended to start a boys’ academy with himself as principal, having falsely awarded himself the degree of Doctor of Laws in English.

The genial, extroverted James enjoyed immediate local success, being appointed a director and secretary of the English & American Bank and secretary of the Southside Virginia Immigration Society. But he couldn’t resist authorising bank loans to many of his new friends on little or no security. When his irregular activities were uncovered after a few months, he was forced to abandon his family, fleeing by the Panama–San Francisco route and landing in Sydney in October 1875, “sick in body and mind,” as he wrote, “and broken in fortune.”

After being deserted by her husband, Caroline James leased Stanley Park, sold their belongings at auction, and returned to England. There she stayed at the same address as James’s father, Joseph Green James, who had long been estranged from his own wife and was practising as a solicitor in Wolverhampton. Caroline would long outlive her husband, dying in Harpenden, England, in 1913, aged about eighty-two.

There is no record of James seeing his wife again after their separation in Virginia, despite the fact he once wrote that she was “the only widow I ever loved.”

Little of this would have been known had not a collection of his writings called The Vagabond Papers, including a chapter by Robert G. Flippen revealing James’s experiences in Virginia, been published in 2016 by Monash University Press. After reading the book, one of Caroline’s descendants began researching her history. Those findings, included in the newly published Vagabond Voyager: The Untold Story, fill most of the gaps.

It is not known exactly when James decided to change his name to Julian Thomas. It may have been after an unsatisfactory few months of freelancing in Sydney. Under that pseudonym he would henceforth live, die and be interred.

James began life afresh in Melbourne, where several relatives, along with Mary Butler and her son, had established themselves. Passing himself off to the rest of the world as Julian Thomas, he won employment with the Argus, Melbourne’s leading newspaper of the time, now writing under the additional pseudonym of the Vagabond. The family kept his secret for many years.

The Vagabond’s sensational weekly articles in the Argus dealt mainly with the miserable lives of Melbourne’s underclass — the poor, the aged, the hungry, the penniless immigrants, the barefoot children, the street prostitutes. His descriptions aroused horror among the paper’s middle-class readers, exacerbated by the mystery of the author’s identity and his ability to insinuate himself into institutions where he acted as a whistleblower on social evils. Many reforms resulted from his efforts.

His articles were so popular that they were subsequently reprinted in the original five-volume version of The Vagabond Papers, with some volumes selling up to 30,000 copies.

This very successful period of James’s life lasted barely two years. When the chief executive of the Argus left for a similar position on the Sydney Morning Herald, the Vagabond followed. But he was unable to repeat his success, although his reports from New Caledonia of an indigenous uprising against French colonial rule remain a landmark of “immersion journalism.”

On his return to Sydney, he descended into alcoholic oblivion, until friends sent him on a cleansing voyage around Asia and the Pacific. The experience led to a new series of articles unique in travel writing at the time.

Because of the success of his Asia-Pacific series, the Argus took James on again in 1883, sending him back to the region to investigate the scandal-ridden labour trade between Pacific islands and Queensland sugar plantations. He sailed extensively with labour recruiters and concluded that the evils of the old “blackbirding” days had largely been overcome.

He was then sent to New Guinea to close down an Argus-sponsored scientific expedition whose leaders were suffering severe illnesses. He brought back many valuable artefacts for the Melbourne Museum.

On his return in 1884, the newspaper sent him on tours around Victorian rural areas to describe the rapidly developing farms and townships, again yielding a valuable series of descriptions that are still quoted and reprinted today. Then he was sent to Britain to cover the International Exhibition of 1886, where the products of Victoria’s booming factories, mines and farms were on display.

Disputes with the Argus management led to the Vagabond’s resignation in April 1887. He immediately found a new audience with David Syme’s more radical daily newspaper, the Age, which sent him back to Europe to write about the Paris Centennial Exhibition of 1889. He also wrote, in French, a fifty-six-page illustrated book, copies of which are now extremely rare, to publicise the event.

In addition to the five-volume Vagabond Papers, he wrote two other books, Occident and Orient: Sketches on Both Sides of the Pacific and Cannibals and Convicts: Notes of Personal Experiences in the Western Pacific, and several plays, of which No Mercy is the best known.

In 1890 the Victorian government appointed him secretary of a royal commission into charitable institutions in recognition of his work in exposing social abuses. James led its members on inspections of many facilities and amassed much evidence, although improvements were constrained by severe economic conditions following the collapse of the colony’s land boom.

James was then able to return to journalistic work for the Age and its weekly journal, the Leader. He was now suffering from cardiac asthma, made worse by his love of good cigars, and his output was limited to articles about Australian affairs.

James died in poverty on 4 September 1896, aged fifty-three, and was buried in Melbourne General Cemetery as Julian Thomas. The following year an elaborate marble monument was erected on the site by public subscription.

In 1912 John Butler Cooper, his putative son, wrote an article in Life, a monthly magazine published in Melbourne, entitled “Who Was the ‘Vagabond’?” Admitting to “a close friendship,” Cooper based his article on what James had told him over many years. It repeated some of the Vagabond’s falsehoods and exaggerations, but gave clues to his true identity and origins.

Cooper left to his heirs a valuable gold watch made in Noumea, no doubt purchased there by the Vagabond on one of his visits and presented to Mary Butler. In a photograph it is shown being worn by Mary in the company of John James. Julianne Spring, a great-granddaughter of John Butler Cooper, has conducted extensive research into the history of the Cooper family since the arrival of the pregnant Mary Butler in Australia, which features in the new book.

Nobody seems to know what happened to the rest of the Vagabond’s possessions, including his copious notebooks, once preserved with the intention of writing an autobiography that he promised “would astonish the world.”

In 2011 the Melbourne Press Club anointed James a foundation member of its Media Hall of Fame. •

Vagabond Voyager: The Untold Story is edited and introduced by Michael Cannon, with contributions by Kay Ashwood and Julianne Spring.