When I was eleven years old, Noël Coward walked into the restaurant where I was having lunch. At our table was a make-up artist, a rather grand lady who worked in film. She whispered loudly: “It’s the Master!” So I have been aware, pretty much all my life, that this is how Coward was referred to in the business. What I did not know until I read Oliver Soden’s big new biography was that the sobriquet was Coward’s idea and he insisted on it from his staff.

When Coward himself was eleven his theatrical career had already begun. Billed, prophetically, as “Master Noël Coward” and managed by his mother (a “Mrs Worthington” avant la lettre), he appeared in a succession of plays in Edwardian London, eventually taking the role of Slightly, one of the Lost Boys in J.M. Barrie’s West End hit Peter Pan. Many years later, the theatre critic Kenneth Tynan wrote of Coward: “In 1913 he was Slightly in Peter Pan, and you might say he has been wholly in Peter Pan ever since.”

Tynan’s implication here is that Coward never grew up, but it would perhaps be truer to say that he hid his adult self behind a series of masks. His entire public persona was a performance — the dressing gown and cigarette holder masking a middle-class upbringing in a house that took in lodgers to make ends meet — and while we might think of him today primarily as a playwright and a singer of songs that displayed his “talent to amuse,” he continued acting almost to the end of his life.

In 1965, in Otto Preminger’s psychological thriller Bunny Lake Is Missing, he played the creepy landlord, Wilson (“an elderly drunk, queer masochist! Hurray! That’s me all over,” he wrote to his friend Gladys Calthrop), and four years later, in his last film, The Italian Job, he was the criminal mastermind, Mr Bridger. The list of acting work that Coward turned down is astonishing and includes the King in The King and I, Professor Higgins in My Fair Lady and the Alec Guinness role in The Bridge on the River Kwai; at the height of Coward mania in the 1930s, he declined an invitation to play Hamlet on Broadway.

In any consideration of Coward’s character, it is important to bear in mind just how famous he was, and how suddenly the fame came upon him. A literary scatter-gun, he wrote something like fifty plays in all, sometimes three in a year, and had already had a degree of success when The Vortex, with its frank (for 1924) discussion of sex and drugs, brought him theatrical notoriety. By the end of the following year, he had four plays running in the West End, including the comedy Hay Fever. He had just turned twenty-five.

Meanwhile, he acted and directed and was already writing revues and songs (at first just words, then the music too). By 1930, he had composed “A Room with a View,” “I’ll See You Again,” “The Stately Homes of England” and “Dance, Little Lady,” and written perhaps his greatest play, Private Lives. He directed its first production that year, starring in it alongside Gertrude Lawrence, whom he had met when they were child actors: “She gave me an orange and told me a few mildly dirty stories, and I loved her from then onwards.”

Private Lives contains English drama’s second-most-famous balcony scene, during which Coward’s new song, “Some Day I’ll Find You,” is first overheard, then sung by Lawrence’s character, Amanda, before becoming the butt of her oft-quoted remark about the potency of “cheap music.” Here’s one of those masks, because behind the self-deprecating humour about his music being “cheap” lies the fact that Coward was a sophisticated songwriter.

The sophistication of the lyrics is obvious — the intricate rhyme schemes are a match for those of his friend Cole Porter — but the music is sophisticated, too. The heavy Charleston syncopations in the verses of “Dance, Little Lady” pull the song dangerously off-balance (underlining his warning to the dance-addicted “little lady” not to be “so obsessed with second best”), while the drooping chromatic gloom of “Twentieth-Century Blues” manages, like the century itself, to be both wearisome and seductive. The melodic line of “Mad About the Boy,” dogged, yet haunting, captures the mood of the four besotted women who tell us they are “glad about” and “sad about the boy,” and speak of the dreams they’ve “had about the boy” (even though there are “traces of the cad about the boy”), while speculating that “Housman really wrote The Shropshire Lad about the boy.”

In “London Pride,” composed during the Blitz, the sophistication is patriotic. As Oliver Soden explains, “[the] song has the harmonic basis of the Westminster chimes and is woven from a street-sellers’ cry — ‘Won’t You Buy My Sweet Blooming Lavender’ — and from the opening phrase of ‘Deutschland über Alles.’” It seems remarkable that Coward, while an adequate piano player, couldn’t read or write music and had to employ an amanuensis to take dictation from his singing and playing. Soden says he “seems almost purposefully [sic] to have made his songs the work of an amateur musician.”

Soden’s Masquerade: The Lives of Noël Coward adopts the overall structure of Tonight at 8.30, Coward’s series of nine one-act plays. But each chapter/act has a unique structure of its own that reflects the variety of Coward’s creative output: plays, musicals, reviews, short stories. Occasionally, Soden allows the people in Coward’s life to speak to each other in pages of pure dialogue (the author stresses that the words are quoted verbatim, even if their context is new), and in the book’s final section, “A Late Play,” there is an extended discussion of their subject by Coward’s biographers, Soden included. The whole approach is arch, no doubt about it, but it works surprisingly well.

Soden proposes Coward, with his quick wit and the clipped precision of his language, as the link between Oscar Wilde and Harold Pinter, notwithstanding the fact that Coward himself had harsh things to say about both the other playwrights. “What a tiresome, affected sod!” was his verdict on Wilde, while Pinter’s early plays, including The Birthday Party, were “completely incomprehensible and insultingly boring.” He came round to Pinter with The Caretaker and the two men became friends, Coward generous with both money (he supported the film of The Caretaker) and advice. Soden relates that Coward even had advice for pop musicians, telling the Kinks’ starstruck Ray Davies, “Always keep a smile on your face when singing about anything that makes you angry.”

One of Coward’s biggest talents was for reinventing himself. He threw himself into war work as an emissary, particularly with the United States, writing, directing and starring in the film In Which We Serve, and finally heading off to entertain the troops. The troops were not always welcoming — they wanted Vera Lynn — and neither were the performing conditions. In Burma, close to the Japanese lines, “the wind, when it changed direction, brought with it the smell of Japanese corpses, stacked nearby in a clearing. Noël vomited into a bucket between shows.”

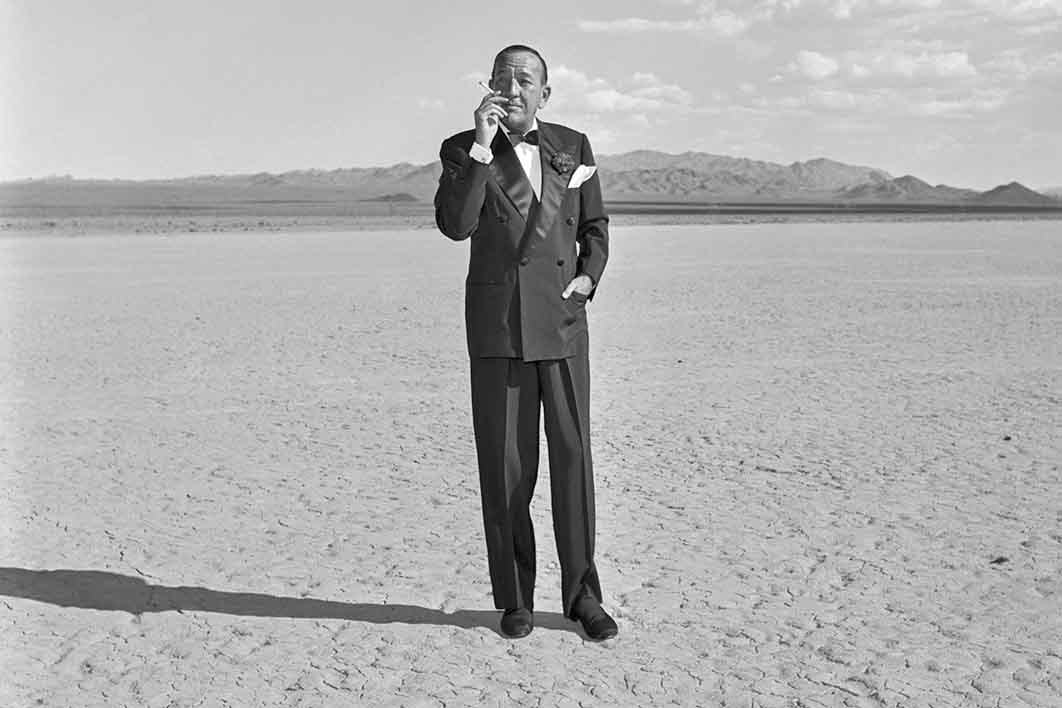

In the 1950s he became a Las Vegas cabaret artist at the mob-run Desert Inn (“The gangsters are all urbane and charming”). Frank Sinatra chartered a plane to send Lauren Bacall and Judy Garland to the show; Cole Porter came to hear Coward’s rewrite of “Let’s Do It”; Zsa Zsa Gabor sent a giant pink teddy bear to his hotel room. Coward’s success hinged on his playing up the image of the urbane “Master.” The celebrity photographer Loomis Dean took him out into the Nevada desert for a photo shoot, and there he stands on the parched earth, clad in a tuxedo, holding now a cocktail glass, now a tea cup and saucer, now a cigarette: the Englishman “out in the midday sun.”

The paradox with Coward’s mask wearing is that it distracts us from the quality of his best work. His songs really do deserve to be mentioned along with those of Porter, the Gershwins and Richard Rodgers. His plays remain important and, even at their wittiest, more serious than the playwright himself would ever allow.

After Coward’s death, Harold Pinter, always a fan, repaid the older man’s generosity with new productions of his plays. Directing Blithe Spirit at London’s National Theatre in 1976, Pinter told his cast: “Noël Coward calls this play an improbable farce. I just wish to make one thing clear — I do not regard it as improbable and I do not regard it as a farce.”

Perhaps, in the end, even the famous generosity of spirit was a mask. If so, it was often tested. Look After Lulu!, Coward’s translation of a Feydeau farce, opened on Broadway in 1959 to a dire review in the New Yorker from Kenneth Tynan. The day it appeared, Tynan was dining alone at Sardi’s, the famous theatre-district restaurant, when Coward walked in, also alone. Tynan had nowhere to hide as Coward padded over to his table.

“Mr T, you are a c—t. Come and have dinner with me.” Tynan recorded that, throughout the meal, Coward was affable and amusing and the review was never mentioned.

Masquerade: The Lives of Noël Coward

By Oliver Soden | Weidenfeld & Nicolson | $34.99 | 656 pages