An election result – especially one as shocking as the 2016 US presidential result – is like a political Rorschach ink blot, onto which commentators project their favourite political scenarios or greatest fears. Most colourfully, film-maker Michael Moore described the result as the “biggest fuck-you ever recorded in human history,” a wakeup call delivered by the white working class to spite “the establishment.” But it’s important to be precise about what happened and to sift through the many explanations on offer.

The most basic point is that Hillary Clinton won the election by almost 2.9 million votes. She received 65.844 million votes to Donald Trump’s 62.980 million, or 48.2 per cent versus 46.1 per cent. Uniquely among presidential elections worldwide, victory in America is determined not by majority vote but by how the popular vote translates into state delegates to the national Electoral College. The clear Clinton majority of popular votes severely qualifies sweeping interpretations of what “the American public” wanted when it voted.

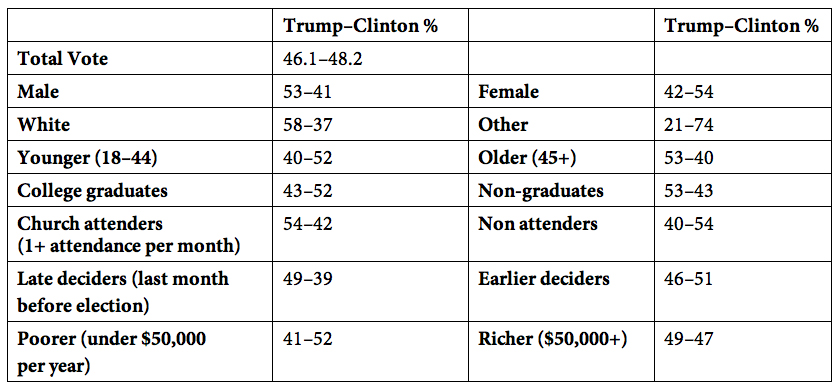

Almost as interesting is the distribution of electoral support, which shows sharp divisions between different social groups. A CNN exit poll of almost 25,000 people found the following:

While Trump clearly won among males, Clinton won equally emphatically among females. Trump won among whites, but only one in five voters from other racial groups supported him. Chasms are evident between older and younger voters, between college graduates and non-graduates, and between those who attend religious services and those who don’t. It was a polarising election.

But it was the geographical distribution of the vote that gave Trump his victory. The Electoral College was founded as a compromise between those who wanted the president selected by Congress and those who wanted a direct election. Its 538 delegates are divided up broadly according to state population, with all but two states electing delegates on a winner-take-all basis. Whether it’s a crushing victory or a razor-fine win, all state delegates go to the victor. So the very big majorities Clinton secured in New York and along the West Coast earned her no extra delegates.

Trump’s victory is the fifth time in American electoral history that the winning presidential candidate has failed to win the popular vote. Three presidential candidates managed this feat during the nineteenth century; much later, in 2000, George W. Bush squeaked into office with half a million fewer votes than Al Gore. Clinton’s 2016 loss is the election where the will of the majority has been most clearly thwarted by the peculiarities of the system.

The large gap between Trump’s and Clinton’s popular vote might fuel moves for reform. But one party, the Republican Party, is benefiting from the Electoral College system so much more than its opponents that any change is unlikely to gain bipartisan support. Ironically, on election day in 2012, when it looked as if the Electoral College distribution for Obama would be more favourable than the popular vote, Trump himself tweeted, “The electoral college is a disaster for democracy” and, later, “This election is a total sham and a travesty. We are not a democracy!”

With surprisingly few states changing sides at each election, the Electoral College system concentrates the contest on a few “battleground,” or swing, states. In the four previous presidential elections this century – two won by the Republican Bush, two by the Democrat Obama – only ten states changed parties. In 2016, those ten were split five each between Clinton and Trump. Among them, the Clinton camp thought she had a good chance of winning Florida and North Carolina, but in the end she lost both by just over 1 per cent.

The key to Clinton’s defeat, though, was the loss of three midwestern states, Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, which had been solidly Democratic in recent elections. They turned out to be the three closest contests: in fact, an election involving over 130 million voters was decided by 77,000 votes across those three states. By such a thread hung an enormous result.

Before the election, it was widely postulated that Clinton and the Democrats were the better organisation, better at strategy and better at turning out the vote. The results suggest otherwise. As the political scientist Simon Jackman wrote, “Trump ads aired in Wisconsin all through the campaign. Clinton made huge ad buys there only late in the campaign, after the FBI announced it was looking at Clinton’s emails again. A similar story holds in Michigan, with Clinton only visiting the state in the last week.”

The economy, stupid?

The loss of these three “rust-belt” states, which have suffered greatly from the declining employment in manufacturing, was the key to Trump’s victory. From 1979 to 2015, while the total population rose by almost 100 million, jobs in manufacturing dropped from 19.3 to 12.3 million. The emerging new economy/old economy split was exacerbated by the regional concentration of its discontents, and their feeling that neither the media nor the politicians were interested in the hardships of the “flyover” states or the fact that their future was anything other than continuing decline.

Some indicators of this divide show up in the national polling. The CNN exit poll found a tied 46–46 result among those who thought their situation was about the same today as four years ago. Among those who thought they were better off today, Clinton won 72–24; among those who felt worse off, Trump won 78–19. A similar trend emerged when voters were asked about future prospects: Trump thrived among the pessimists, while Clinton won among the optimists: Of the one third who thought that life for the next generation will be worse than today, Trump won 63–31.

In most polling, though, the national averages submerge the regional phenomenon. As sociologist Michael McQuarrie observed, “The Clintons are avatars of free trade, financialisation and identity politics, a triumvirate of characteristics that associates them pretty directly with what many people associate with the causes of Rust Belt decline and crisis.” A Democratic congresswoman, Elizabeth Esty, observed that the sense of disrespect felt by people who have lost work to new machines, technology and, in some cases, globalisation is palpable. Among displaced workers, she warned, cultural unease was linked with economic anguish, and this was fertile ground for Trump to exploit.

The long-term context for the election battle was increasing inequality in the US, and the failure of median incomes to rise substantially even during periods of economic growth. Somewhat ironically, the last two years of the Obama presidency saw the most substantial rise in median incomes for a long period. But just as with another favourite Trump theme – the high crime rate, which has in fact fallen substantially in recent decades – either the improvements have been too small to dent the discontent, or perceptions have not kept pace with changing realities.

Although lower-income groups were still more likely to vote for Clinton, a key to Trump’s victory lies in how his populism won some of these groups over in a way that none of the other recent Republican candidates could. Mark Danner reported one Trump supporter making the point clearly: “The white working class in America. The ones paying for all the others. Finally we’re getting someone who’ll do something for us.” This sentiment has been widespread in the poorer, “flyover” states for a long time: as far back as 1968, George Wallace, the third-party racist candidate, attracted support from struggling white voters who saw themselves in conflict with those above and those below.

A turnout problem?

With voting voluntary in the United States, parties win elections as much by mobilising their own voters as by converting people from the other party, or persuading the uncommitted. Straight after the election, it became popular to attribute the result to Clinton’s inability to enthuse her potential voters: she had not given them a positive reason to vote for her, the argument went, and this was reflected in the low turnout figure.

When all the votes were finally counted, though, turnout in 2016 was slightly higher than in 2012, with 60 per cent of eligible voters participating compared to about 59 per cent. That’s less than the recent peak of 62.2 per cent, which brought Obama to power in 2008, but considerably higher than the 55.3 per cent who voted when Bush defeated Gore. A turnout figure of above 60 per cent would undoubtedly have favoured Clinton.

Sometimes potential voters stay home because the result seems foregone. It’s true that the forecasters were all but unanimous in predicting a Clinton victory, but it seems unlikely that in such a ferociously fought campaign this kept large numbers of people away from the polling booths. More plausible is the idea that many voters, among them apparently George H.W. and George W. Bush, didn’t vote because they strongly disapproved of both candidates.

Another set of turnout-centred explanations focuses on ease of voting. In the US, state government control of most features of the electoral system has led to many abuses. At the moment, as political scientist Pippa Norris has pointed out, Republican states in particular have gerrymandered electoral boundaries in the House of Representatives to guarantee Republicans a greater proportion of seats than votes. States also control legislative and administrative arrangements for presidential elections.

The Voting Rights Act was a federal response to some of the problems state legislatures had created. In states with historically disadvantaged minorities, changes to election regulations could only be made with federal approval. Since a 2013 Supreme Court decision, though, they are free to make their own decisions. North Carolina, for example, has introduced tougher voter ID laws, to counter a much-publicised but largely non-existent problem of voter fraud, and other restrictions. It has also cut seven days of early voting and made out-of-precinct voting more difficult. Some states have greatly reduced the number of polling stations, largely in pro-Democrat areas; one result, in Charlotte, North Carolina, was four-hour queues to vote in some places, and a 16 per cent decrease in black turnout compared to 2012. It is impossible to put a figure on how much this manipulating of the mechanics of voting changed the result.

A Clinton problem?

In any two-horse race, explanations of the result often focus on the shortcomings of the defeated candidate. Beforehand, Trump was widely seen as unelectable – “this phony… this misogynist, this demagogue, this predator, this bigot, this bore, this egomaniac, this racist, this sexist, this sociopath.” That such a person won has put the focus on the perceived failings of Clinton.

As early as May, Trump strategists believed that if “we could keep the focus on Clinton, we win.” “Trump views Hillary Clinton as the personification of what’s rotten in Washington,” said one. “She was [already] defined as someone that people don’t like and don’t trust, and all we had to do was reinforce the existing narrative.” This was done through endless repetition of phrases such as “Crooked Hillary” and “drain the swamp.”

Clinton’s decades in Washington – as first lady, senator and secretary of state – might normally have been an electoral asset. But Trump managed to frame the campaign as outsider versus insider. Her long proximity to power made her a symbol of dynastic entitlement, and then her opponent conjoined it to the theme of ineffectiveness by asserting that she had spent thirty years doing nothing. At the least, there was a mismatch of campaigning styles between Clinton and Trump and a disjunction between Clinton and the mood of (parts of) the nation. While Trump paraded slogans devoid of any policy content, Clinton often recited “wishlists of policies as if reading the minutes from a committee meeting,” according to the Economist’s Lexington column. As an Economist editorial observed, “It is hard to think of a politician less suited than Mrs Clinton to combating America’s rock-throwing mood.” Clinton is a “self-confessed incrementalist. She believes in the power of small changes compounded over time to bring about larger ones,” added Lexington. Her command of policy detail was no match for Trump’s “vision” of wholesale change.

Did Clinton lose because she was a woman? It is impossible to ignore the extra venom it added to the mix; but it is also impossible to know if it changed any votes. Certainly, as the CNN poll showed, men preferred Trump, but we lack data on the extent to which conscious or unconscious misogyny – as opposed to factors like class and income – contributed to that figure.

The Trump camp saw what his chief of communications, Kellyanne Conway, called Clinton’s “never-ending scandalabra” as one of their great assets. The scandals often ran together to create a general impression of murkiness, but there were three main charges. The first was Clinton’s alleged culpability as secretary of state for the deaths of four Americans in Benghazi in 2012. Although seven official investigations have shown she had no case to answer, the accusations kept being repeated.

The second was the financial success and governance arrangements of the Clinton Foundation. Since Bill Clinton left office in 2001, he and Hillary have given 728 talks involving US$154 million in fees, with Bill earning around 86 per cent of the total sum. This mix of personal enrichment, foundation charitable activities and absurdly large speaking fees, mixed with access to power and patronage, in many ways embodied the swamp Trump claimed he wanted to drain: the insider culture, its sense of entitlement and the blurring of lines between public and private roles. If anything, Clinton was lucky that this didn’t become an even bigger issue – although, of course, the Trump Foundation was even more scandalous.

The third issue, and the one most prominent during the campaign, was her use of a private email server when she was secretary of state. This first became controversial as she was beginning her presidential run in March 2015. It was alleged that she had used the private server as a way of concealing awkward facts, that she had destroyed evidence, and that her arrangements were a threat to national security. That reaction might have been hugely overblown, but as the New York Review of Books’s Elizabeth Drew observed, “the server underlined another aspect of the Democratic candidate that bothered people – arrogance: people concluded that the Clintons didn’t feel that they needed to play by the same rules other people did.”

A campaign problem?

The great majority of voters choose the candidate of the party they support, especially in close elections. But enough people remain undecided about whether to vote and whom to support until close to polling day that developments during the campaign can be decisive. Trump was a unique campaigner, and it was his style that made the 2016 campaign so compelling and so divisive.

Trump set a xenophobic tone when he launched his campaign in June 2015. “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best,” he asserted. “They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.” Apart from Mexicans, there were attacks on other outsiders – Chinese and Muslims figuring most prominently, but even America’s “freeloading” allies figured as targets. Only Russia escaped. One of the architects of the Republicans’ post–civil rights strategy from 1968 on, Kevin Phillips, once observed that all politics comes down to “who hates who.” And, like nearly every other aspect of Trump’s campaigning, it was polarising and double-edged.

By many conventional measures, the Trump campaign was a disaster. There was more disunity among prominent Republicans than in any previous campaign. The last several presidents and presidential candidates criticised him, and some even refused to endorse him. His first chief of staff, Paul Manafort, had to resign when it was revealed he had worked as a political consultant for the Russian-backed government in Ukraine. His replacement, Steve Bannon of the extremist “alt-right” website Breitbart, had an even greater reputation for divisiveness and irresponsibility.

Trump lost all three televised debates, according to both the polling and the pundits. He let “the ugly inner Donald” go on full public display in his tweets and public statements. It was a high-risk tactic, but it had two redeeming features politically. The first was that it seemed like authenticity. His rudeness was a form of candour, proof that he was not a career politician; his lack of experience in public office meant that he was untainted by the insider culture; his aggression was proof of his willingness to break through the inhibitions of political correctness. This was all buttressed by a simple but strong campaign theme – Make America Great Again.

His willingness to shock the political class was central to his appeal, writes journalist Mark Danner, and “his gargantuan narcissism makes him so mesmerising to watch.” His unpredictability made him newsworthy. As political scientist Thomas Patterson observed, he got more coverage than Clinton week after week – 15 per cent more, an unusually large difference in a presidential campaign. Although he generated much critical coverage of himself, he was also succeeding in directing the campaign’s content and tone. But the whole strategy seemed to come undone in early October.

The respected columnist E.J. Dionne says that the trajectory of the 2016 campaign can be divided into BV and AV, before the video and after the video. On Friday 7 October, the Washington Post released the notorious tape of Trump talking to a TV presenter about his attitudes towards women. Despite Trump’s attempts to dismiss it as “locker room banter,” it dominated the media like no other campaign revelation. Around twenty-five Republican governors and congressional members withdrew their endorsement of Trump, partly perhaps as a moral reaction, but also out of self-preservation.

Over the next two weeks, around a dozen women came forward saying that Trump had inappropriately kissed or groped them. In response, Trump unleashed a deeply personal string of attacks on them. At the same time, his attacks on Clinton and others seemed to become ever more desperate. An increasingly common theme was that the polls were rigged: “The election is absolutely being rigged by the dishonest and distorted media pushing Crooked Hillary – but also at many polling places – SAD.” The presidential election was “one big fix” and “one big, ugly lie.” Before the third debate, he proposed that Clinton be drug tested, asserted that Clinton had had secret meetings with bankers “to plot the destruction of US sovereignty,” and promised to jail her. Columnist Michael Gerson called it “Trump’s crackup.”

The post-tape assumption that Trump would lose the election provoked many October obituaries examining where and why Trump had failed, and claiming insights into his thinking. “Donald Trump has virtually stopped trying to win this election…” wrote a New York Times columnist, “and is instead stacking logs of grievance on the funeral pyre with the great anticipation of setting it ablaze” after he loses. Others diagnosed where the Republicans had to go after their 2016 failure: “If Republicans truly want to save the Republican Party,” a Washington Post columnist advised, “they need to go to war with right-wing media.”

But when Trump seemed to be at his nadir, when the political world had already written his obituaries, when even leading psephologist Nate Silver put Clinton’s chance of winning at above 85 per cent, the campaign had one final and fatal twist. Just twelve days before the vote, FBI head James Comey announced that emails found on the laptop of disgraced Democrat politician, Anthony Weiner – the husband of Huma Abedin, one of Clinton’s closest aides – had led the Bureau to reopen the investigation into Clinton’s use of a non–State Department server, which it had closed the previous July.

Comey’s statement violated two FBI policies: never publicly discuss an ongoing investigation, and never take an action affecting a candidate for office close to election day. The political fallout was immediate and intense. The statement revived an issue that had plagued Clinton for eighteen months; it created a general sense of impropriety yet didn’t offer a specific charge that could be refuted.

The Trump team was flabbergasted but delighted. Comey had re-energised its foundering campaign. At his next rally, Trump was unrestrained in his rhetoric about the “criminal” and “illegal” conduct of Clinton. The only reason for the FBI to reopen its investigation was that “very, very serious things must have been found.” Clinton, he said, had “set up an illegal server for the obvious purpose of shielding her criminal conduct from public disclosure and exposure knowing full well that her actions put our national security at risk… Hillary Clinton is guilty. She knows it. The FBI knows it… now it’s up to the American people to deliver justice at the ballot box.”

After nine days of uncertainty – and voluminous abuse, assuming Clinton’s guilt on unspecified charges, from Republicans and right-wing pundits – the FBI announced it had found nothing. It was just days before the election, and millions had already voted, and even the clearing of Clinton made the issue prominent again. Later, in December, when the court documents were released, there was more outrage. As the Washington Post’s Dana Milbank observed, the newly discovered emails were “irrelevant or redundant.” Nothing in them gave the slightest basis for Comey’s dramatic public announcement.

The evidence for the importance of this episode is strongly suggestive. Thomas Patterson’s charting of news coverage showed that in the second-last week of the campaign 23 per cent of Clinton’s coverage focused on the issue, rising to 37 per cent in the final week, hardly a positive note on which to finish a campaign. Nate Silver has said that without the FBI intervention, Clinton almost certainly would have won. As the table above shows, late deciders went for Trump by a ten-point margin. Evidence from some of the swing states is even more telling. As Silver wrote, “Late deciders went for Trump by 17 points in Florida and Pennsylvania, by 11 points in Michigan and 29 points in Wisconsin.”

Comey’s intervention was doubly disturbing given his organisation’s passive response to evidence of Russian hacking of the Democratic National Committee. He refused to join an administration statement on 7 October naming Russia as the perpetrator of the hacks because, he contended, the FBI shouldn’t be seen as injecting itself into politics close to an election. An FBI officer telephoned the IT helpdesk at the nearby Democrat HQ, but never went there in person, the organisation didn’t initiate any counter or defensive actions, and it only admitted publicly that it had evidence of the hacking well after the election (and only then after being pushed by the CIA).

While the electoral impact of Comey’s intervention is fairly clear, it is impossible to be conclusive about the impact of the Russia–WikiLeaks release of material against the Democrats. Although no major scandals resulted, the distracting noise created by the leaks made the Democrats’ campaigning task more difficult. The release did rehabilitate WikiLeaks in the eyes of many Republicans, however. In 2013, Republicans viewed the organisation more negatively than positively by a 47-point margin. (Among Democrats, the figure was minus 3.) But by December 2016, Republicans viewed WikiLeaks more postively than negatively by a 27-point margin – a 74-point swing. Indeed, Trump told one crowd: “Boy, we love WikiLeaks,” a big change from the earlier cries of treason.

This has been a unique and uniquely awful campaign. It is hard to know if it is a harbinger of political contests to come. Trump triumphed, even though he won far fewer votes than his opponent, and it is perhaps fitting that he enters the presidency with the highest disapproval rates ever recorded.

After all recent elections, the Pew Research Center has asked the public to give presidential candidates a letter grade for how they conducted themselves during the campaign. In 2008, Obama received As and Bs from 75 per cent. The lowest so far was George H.W. Bush in 1988, who received high marks from just 49 per cent. In 2016, Trump received A or B from just 30 per cent, the worst ever by a large margin.

Another pollster, Gallup, has gauged the pre-inauguration favourability ratings of presidents-elect since 1993. The previous worst was George W. Bush in 2001, with a 62–36 (+26 rating); in 1993 Clinton had 66–26 (or +40), and in 2009 Obama had 78–18 (or +60). This year, Trump has 40–55 (or –15), making him the first president to begin office with a negative rating. •