Until three weeks ago, I’d never looked into the eyes of people listening to my music. In the concert hall, you see the backs of their heads and notice if those around you are fidgeting or glancing at their watches, idly riffling through their programs or pulling out their phones to check social media. (She’s probably posting something nice about my piece, you reassure yourself.)

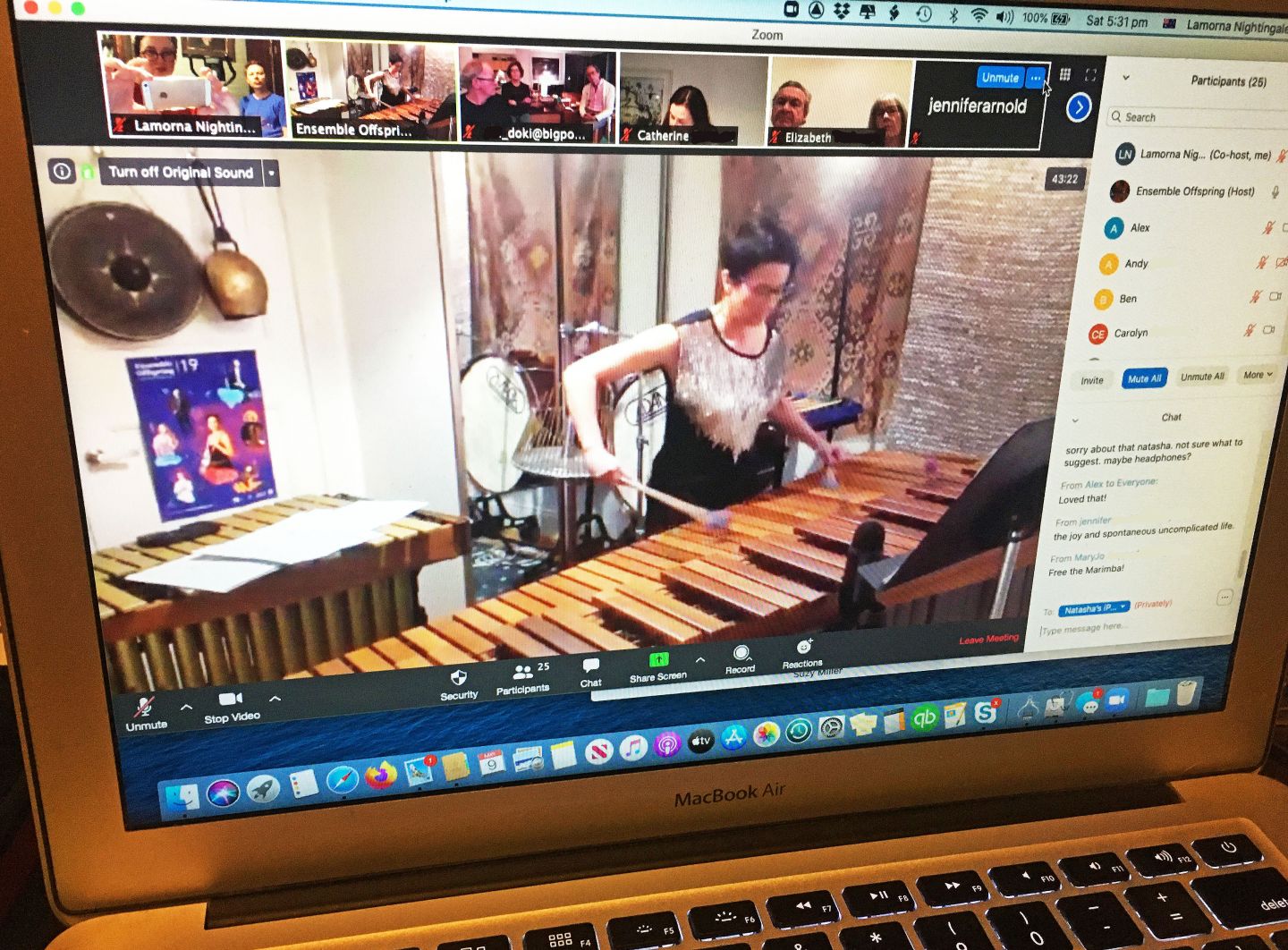

On Zoom, it’s different. At Claire Edwardes’s concert last month, the Sydney percussionist played my vibraphone piece, Hook, and there they were: the paying public, with glasses of wine and bowls of nuts, watching and listening from the privacy of their homes. Except there wasn’t much privacy. One could look not only into their eyes, but also into their living rooms. It bordered on voyeurism, yet it felt collegial.

Claire introduced the short pieces in her hour-long program and, following each performance, the audience members in their little on-screen boxes unmuted themselves to submit their applause. They were also invited to comment on what they’d heard. And they were kind to me and my piece, even though I was, to them, an invisible presence, the camera perched on top of my monitor having chosen this moment to go on the fritz.

I’ve been wondering, since, about the place and role of the composer in the concert hall. Composers are mostly not performers; in rehearsal we may work with performers, but at the performance, when they’re up on stage playing our music, we’re in row M. If the piece is well received, we will probably be called upon to take a bow, but that will be the extent of our involvement on the night. Mind you, once the bow is taken and the figure in row M outed as the composer, interesting interactions often occur with other audience members.

There are those who want to tell you they enjoyed your music (the people who haven’t enjoyed it mostly keep away), some of whom will have questions. My favourite responses involve the listeners who tell you how the piece made them feel or what memories it conjured. I was once told, by a farmer in northern Tasmania, that she had been reminded of getting up in the middle of a freezing winter’s night to assist with calving. The piece was called Pastoral.

Audience feedback is important to all musicians — even, I suspect, to those who claim otherwise. Composers are no different. Ours is a solitary activity. Consumed by the need to get the music right, all else goes out of the window, and at that point the audience is the last thing on your mind. If the music doesn’t satisfy you, you’ll be offering the listener either damaged goods or a well-made fake. The process of rehearsing isn’t that different. It might not be solitary, but it will likely be hermetic. But there’s no point to any of it — those weeks or months of composing, those hours or days of rehearsal — without the audience at the end.

It’s a triangular relationship between composer, performer and audience, and it’s only slightly different when the composer and performer are one and the same. Musicians might believe they know what their music means when they write or sing or play it, but individual members of an audience make new meanings as they listen. We hear the same music, but feel it differently. If it sounds, to one listener, like a cow giving birth, then that is what it is.

Online concerts are no different. Indeed the listeners’ responses may be more varied than ever, now we are all more alone. But something is lost when we no longer sit tightly packed in the same hall having our individual experiences alongside one another. It’s an unspoken yet strongly felt emotional connection that comes via the music. Is it body language, is it breathing that conveys it? At its most powerful, it is a kind of magic, and for the time being we are having to do without it.

Last week, Opera Australia announced the cancellation of its entire winter season. This included the postponement of Rembrandt’s Wife, my opera written with Sue Smith, which was to have had seasons in both Sydney and Melbourne. Sue and I had already had a meeting with the director, the evidently brilliant Tabatha McFadyen, who’d have been making her debut in this new production; Mark Thompson’s designs were ready to go; I could barely wait to hear one of Australia’s great singers, Taryn Fiebig, in the dual roles of Saskia van Uylenburgh and Hendrickje Stoffels.

Above all, though, I wanted to be in row M, sharing the experience of this brand-new production with an audience of total strangers, and gleaning their responses to a piece of work that had taken over my imagination for nearly eighteen months. That moment of direct communication is now indefinitely on hold, as are countless others. In company with most musicians, my schedule of live performances for 2020 is completely blank.

But as online concerts increasingly pop up, and little groups of listeners peer into each other’s homes, it may be that this new method of musical communication, one that allows us to observe the performer at close quarters and then discuss the music with the performer and composer, will remain. In a way, these sorts of events predate the concert hall. They are authentic chamber music — from the performer’s chamber direct to yours — and they permit a level of engagement and interaction that the concert hall can’t match. They will never match the excitement of a live event with an audience — the opera theatre, the jazz club, the rock band in the pub, the outdoor festival — but for musicians prepared to reveal more of themselves and audiences keen to watch musicians at work from just a metre or two away, there’s surely no going back. •

Funding for this article from the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund is gratefully acknowledged.