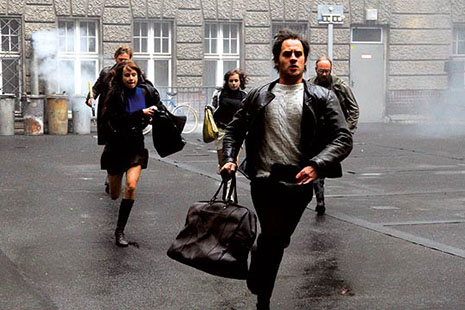

THE Baader Meinhof Complex may not be the worst of the many films about the German Red Army Faction, but it would have to come close. It achieves this distinction despite the resources available to director Uli Edel and producer Bernd Eichinger – the film had a budget worthy of a Hollywood blockbuster – and despite a stellar performance from Moritz Bleibtreu (playing Andreas Baader) and solid contributions from three other lead actors: Martina Gedeck (as Ulrike Meinhof), Johanna Wokalek (as Gudrun Ensslin) and Bruno Ganz (as the head of the German Federal Police, Horst Herold). And it does so despite the film’s high entertainment value: it is an action-filled drama with an intriguing plot that leaves audiences on the edge of their seats.

In fact, The Baader Meinhof Complex would be a genuinely interesting film if it did not aspire to be “as authentic as possible” (in Edel’s words) – if it did not pretend to be a true representation of facts. And even that might not be such a big problem if it were not for the significance of these “facts” in postwar West Germany, and for the crucial role their memories have played in Germany over the past three decades.

The film tells the story of Andreas Baader, a small-time crim, and Gudrun Ensslin, the daughter of a Protestant priest, who in 1968 carried out an arson attack against a Frankfurt department store to protest against the American war in Vietnam. They were caught, tried and sentenced to three years in jail. After a year in prison, they were released after their lawyers appealed the conviction. In November 1969 the Federal Court rejected the appeal, and Baader and Ensslin went into hiding to avoid being rearrested to serve the remainder of their sentence. A few months later, Baader was caught and returned to prison.

On 14 May 1970, Ensslin, the prominent left-wing journalist Ulrike Meinhof, and several accomplices engineered Baader’s escape from an academic institute he had been allowed to visit under guard, ostensibly to co-author a book with Meinhof. One of the institute’s employees was shot and seriously injured. The day of Baader’s escape marks the birth of what became known in Germany as the Baader Meinhof gang (or Baader Meinhof group). In 1971, in a manifesto describing the group’s aims, Meinhof first used the term Rote Armee Fraktion (Red Army Faction). The acronym RAF stuck and survived her and the group’s other founding members.

Initially the group, which in 1970 included more than twenty people, travelled to Jordan to a training camp run by the PLO’s Fatah faction. Unwilling to submit to the Palestinians’ military discipline, they soon returned to Germany the same way they had left it: via East Berlin. They now saw themselves as urban guerillas. Their role models were the Tupamaros – the Movimiento de Liberación Nacional in Uruguay – which since the late 1960s had resorted to kidnappings and assassinations in its fight for social justice.

Over the next two years RAF members robbed banks to fund their life on their run and otherwise tried to evade arrest by the police force, which was throwing all its resources at hunting them down. In the course of this unprecedented search, several people who either belonged to the RAF or were wrongly thought to be terrorists were shot dead by police. In October 1971, the first police officer was killed by a member of the RAF.

In May 1972, the group intensified its activities. When the American air force used mines to shut down North Vietnamese ports, the RAF began targeting the American army, which then had hundreds of thousands of GIs stationed in the former American zone of West Germany. Bombs exploded at American facilities in Frankfurt and Heidelberg. Four American soldiers died and many others were injured. As revenge for the group members shot by the security forces, the RAF also detonated bombs in police stations. Several people were injured after the group hid a bomb in a building housing editorial staff of newspapers belonging to Axel Springer, whose mass circulation tabloid Bild had a long tradition of stirring up hatred against the left and which was held responsible for the shooting of Rudi Dutschke, the charismatic leader of the West German student movement.

In June, soon after the largest police operation in German history, when the president of the German Federal Police was, for a day, put in charge of the republic’s entire non-military security personnel, Baader, Ensslin and Meinhof were arrested. But even with nearly all of those who had made up the RAF in 1970 and 1971 either dead or behind bars, and the group’s leaders in prison, the confrontation between the West German state and the RAF was far from over.

Those in prison went on a series of hunger strikes to protest against the conditions under which they were held. Initially they were not allowed any contact with other prisoners and kept in soundproof cells with white interiors lit day and night by fluorescent tubes. In 1974, one of the RAF prisoners, Holger Meins, died – he had starved himself to death. While he lay dying, his lawyer tried in vain to convince the prison authorities that he required urgent medical attention. In 1976, Ulrike Meinhof committed suicide in prison.

The RAF members still at large became increasingly concerned about freeing their imprisoned comrades. In 1975, another militant group, the Movement 2 June (named after the day when police in Berlin killed the student Benno Ohnesorg during a demonstration against the state visit of Shah Reza Pahlavi of Iran), abducted Peter Lorenz, a prominent conservative politician. In return for Lorenz’s freedom, the federal government released five convicted terrorists from prison and flew them to Aden. The RAF was clearly hoping that they, too, would be able to force the government’s hand.

On 5 September 1977, an RAF commando ambushed the convoy of the powerful president of the German Employer’s Federation, Hanns-Martin Schleyer, killed his driver and the three police officers who acted as his body guards, and took him hostage. They demanded the release of ten RAF prisoners. This time, the government decided not to give in to the demands.

To increase the pressure on the German government, on 13 October 1977 four Palestinians hijacked a Lufthansa plane on its way from Mallorca to Frankfurt. They plane eventually landed at Mogadishu, the capital of Somalia. With the tacit support of the Somali government, German special forces stormed the plane, killed three of the Palestinians and freed all passengers and crew except for the pilot, who had been shot dead by the hijackers.

A few hours later, Baader, Ensslin and a third RAF prisoner, Jan-Carl Raspe, lay dead in their cells in the high-security wing of Stammheim Prison. A fourth RAF prisoner, Irmgard Möller, had life-threatening stab wounds. Baader and Raspe had been shot; Ensslin was found hanged. The German government has always maintained that the three prisoners had committed suicide when they received news of the failed hijacking. Möller, who survived the stabbing and was released from prison in 1994, has always maintained that somebody had tried to execute her. The day after the deaths in Stammheim, the RAF killed Schleyer.

THAT – in an abridged version – is the story told by The Baader Meinhof Complex. Eichinger and Edel clearly pride themselves on telling that story exactly as it happened. And their attention to detail is indeed amazing. In restaging the demonstration against the Shah of Iran and the death of Ohnesorg, they not only shot all scenes at the original locations and allowed audiences to recognise a famous image, in which a woman holds Ohnesorg in her arms, but they ensured that the numberplates of the car carrying the Shah were accurate and that the magazines on sale at a newsagent’s stall were exactly those that would have been on sale on 2 June 1967. They not only rebuilt the part of the Stammheim prison where Baader and Ensslin were held, but obtained original bathroom fittings and door locks from Stammheim.

According to Edel, The Baader Meinhof Complex is meant to be “a semi-documentary film.” In order to convey that sense, the camera is often static, merely witnessing and documenting the unfolding action. But while the film accurately represents the angle of every shot fired, it is equally remarkable on account of its omissions. The film is about those who belonged to the RAF, and supposedly reconstructs their perspective. But more often than not it resembles a freakshow, with Baader, Ensslin and Meinhof shown as psychopaths and fanatics. (Which is not to say that they were likeable characters: Baader, in particular, was a misogynist and bully – that he became a terrorist rather than a gangster was probably more the result of opportunism than of political conviction.)

The context that gave rise to the RAF is little more than background noise; while the film features the demonstrations against the Shah’s 1967 visit to Berlin and a speech by Dutschke, the connection between the student rebellion and the RAF seems accidental. And while there are references to the war in Vietnam, there is no mention of Germany’s Nazi past, which probably loomed equally large in the student protests and in the emergence of the RAF.

The film does not provide any clues about the significance of what became known as Deutscher Herbst, the German Autumn: the forty-three days from the abduction of Schleyer to his murder. The conflict between the state and the RAF transformed the Federal Republic. In order to combat the threat of terrorism, the West German parliament passed a series of laws that restricted contact between those accused of terrorism and their defence lawyers and targeted those who sympathised with terrorists. West Germany came very close to becoming exactly what the RAF had claimed it was all along: a police state. For a while, civil liberties became an endangered species.

At the time, the overwhelming majority of Germans applauded the heavy hand of the authorities. Members of the liberal intelligentsia took out newspaper advertisements to distance themselves from the RAF. The few who did not profess their unconditional love for the government, among them Nobel Prize winner Heinrich Böll, were held personally responsible for crimes attributed to the RAF. The West German media agreed not to print information that could jeopardise the police effort; Germans who wanted to keep informed had to resort to reading Danish, Dutch, British or French newspapers.

While Baader & Co seem to have little in common with radical Islamist suicide bombers, the history of German terrorism holds important lessons for today. Close attention to that history could help us appreciate what happens when civil liberties are deliberately eroded to assist the security forces in their fight against politically motivated violence.

More than thirty years after the German Autumn, it is still unclear how close to the brink the fledgling republic was. During those forty-three days, decisions were made in the Großer Krisenstab, a committee made up of senior politicians from both sides of politics, state premiers, the federal prosecutor and the president of the German Federal Police. This committee had been convened by the government, although there was no provision for it in the West German constitution. Its meetings appear to have been neither recorded nor minuted. But in recent years, some participants have provided hints about the discussions that took place behind closed doors. According to those accounts, the Krisenstab seriously considered treating all RAF prisoners as hostages, threatening to execute them, and carrying out that threat if Schleyer were not freed.

More than thirty years after the deaths of Baader, Ensslin and Raspe, questions remain: how did they manage to smuggle guns into the most secure prison in Germany without the authorities’ knowledge? Did their suicide – if it was suicide – really come as a surprise to the authorities?

The Baader Meinhof Complex does not gesture towards any uncertainties. It implies that its ambition to tell the story exactly at it was is realistic because all the details of that story have been established beyond doubt.

This is the second film made by Bernd Eichinger that claims to show, once and for all, a past exactly as it was. The first was Der Untergang (Downfall), about Adolf Hitler’s last days in the Reichskanzlei. There are many parallels between Downfall and The Baader Meinhof Complex, not least their success at the box office (although the former attracted almost twice as big an audience in Germany as the latter).

Two of these parallels are crucial. Like Downfall, The Baader Meinhof Complex reduces a complex past involving all Germans to a drama whose principal actors are psychopaths. And both films, and their claims to get even the tiniest detail right, are based on books written by men with an obsession. Downfall relies on a book by Joachim Fest, a conservative journalist who for many years made it his life’s mission to research and write Hitler’s biography. The Baader Meinhof Complex is based on a book of the same title by Stefan Aust, a liberal journalist, who once worked for the same left-wing magazine as Ulrike Meinhof but went on to become editor-in-chief of the news magazine Der Spiegel.

While Fest’s book about Hitler’s last days, Der Untergang, was published only a couple of years before the film of the same title, Aust’s Der Baader Meinhof Komplex predates Eichinger’s film by more than twenty years. The insistence that it must be possible to tell the story of the early years of the RAF as an action-packed drama featuring a bunch of sick lunatics is in itself evidence of the fact that in the mid-1980s, when the RAF still existed, the wounds of the German Autumn were still fresh.

Now, the RAF is long buried. There are plans to pull down the notorious wing of the prison in Stuttgart-Stammheim, where Baader, Ensslin and other RAF prisoners were kept. Only one former RAF member, Birgit Hogefeld, is still in prison. Christian Klar, one of the leaders of the RAF’s second generation, sentenced to life in prison plus fifteen years, was released at the end of last year. But the heated debates about his release indicate that the old (pre-1990) Federal Republic’s biggest trauma has not yet been put to rest.

The eagerness with which German reviewers hailed The Baader Meinhof Komplex last year as the definitive and final word on the RAF is also testimony to the scars left behind by the German Autumn. Admittedly, the film may have also been intended (and was praised by German commentators) as an antidote to overly sympathetic accounts of the RAF, and to the hagiographic treatment Ulrike Meinhof, in particular, has received at times. The mythologisation of the RAF by former or current members of the German left is as much evidence of the difficulty to work through the phenomenon of the “RAF” as is Eichinger’s, Edel’s and Aust’s obsessive recreation of the 1970s. (It should also be mentioned, however, that there have been very successful attempts at understanding the RAF and the Germany that gave birth to it, most notably Andreas Veiel’s 2001 film Black Box Germany.)

Eichinger’s action movie will not be the last word on Andreas Baader, Gudrun Ensslin, Ulrike Meinhof, the RAF and the collective paranoia that gripped the Federal Republic of Germany in the autumn of 1977. Nor is it likely that this will be Eichinger’s last attempt at confronting the big issues of twentieth-century German history. The most obvious next project for him would be a film about the Stasi. Watch out for the psychopaths allegedly responsible for the pervasiveness of betrayal in East Germany… •