“If they can do this to me, they can do this to anyone,” Donald Trump declared the day after he became the first former US president found guilty of felonies and the first major-party candidate to run for office after having been found guilty of a crime. In an effort to turn the conviction to his advantage, he continued: “I’m willing to do whatever I have to do to save our country and save our Constitution. I don’t mind… It’s my honour to be doing this, but it’s a really unpleasant thing, to be honest, but it’s a great honour.”

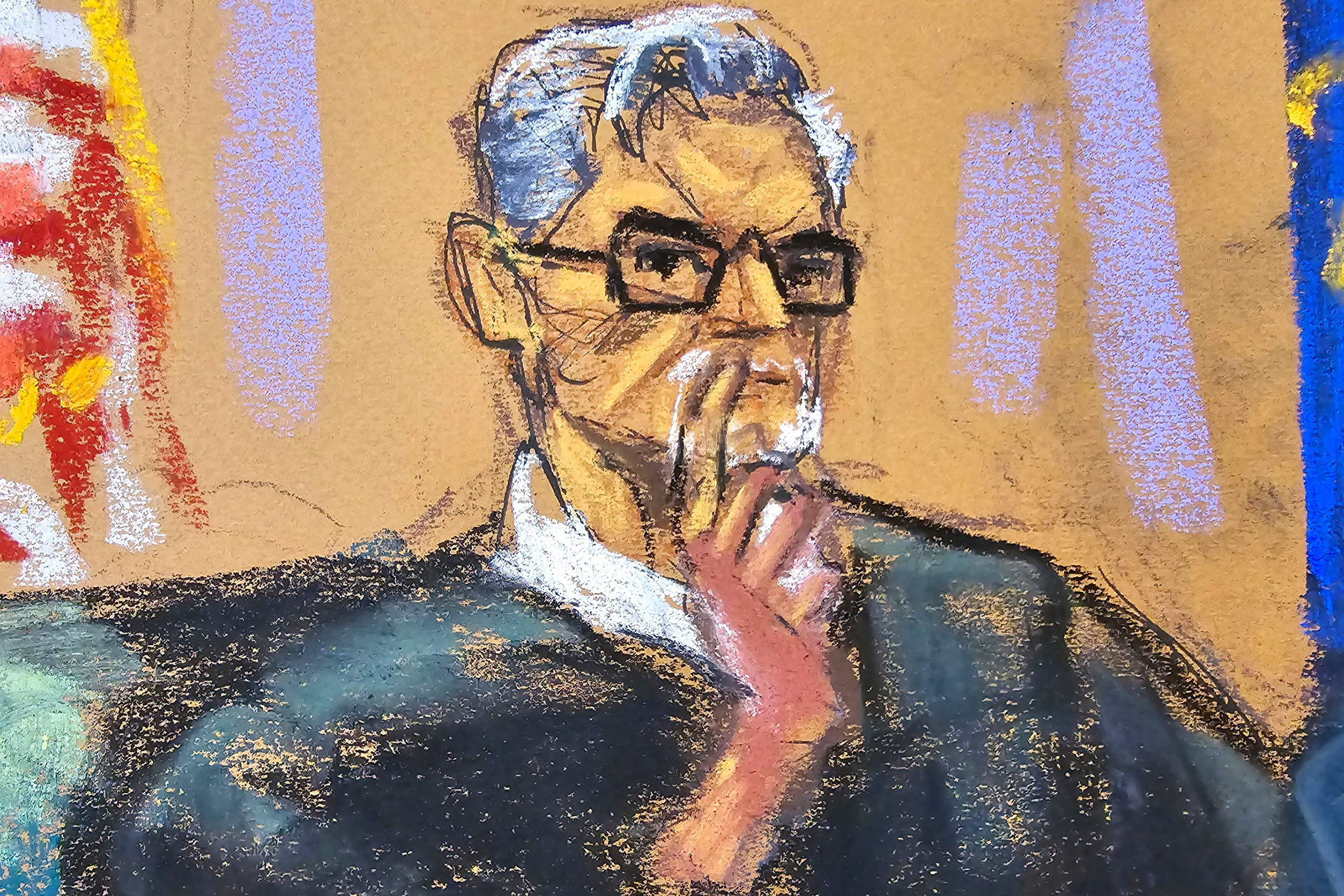

Beneath this bravado he will undoubtedly be worried about his sentencing, which is scheduled for 11 July, just days before the Republican Convention. Judge Juan Merchan has wide discretion to choose between prison, probation, conditional discharge, fines, travel restrictions or house arrest. The maximum punishment would be four years in prison and a $5000 fine for each of the thirty-four charges of falsification of business records; a recent survey of similar cases brought by the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office found that roughly one in ten resulted in incarceration.

“We’re going to be appealing this scam,” said Trump. “We’re going to be appealing it on many different things.” Although he can’t do that until after the sentencing, he and allies including House speaker Mike Johnston are already pushing for his appeal to be taken up by the US Supreme Court. But that can only happen in the unlikely case that he and his lawyers raise a legitimate federal question during the appeals process.

One thing is certain: Trump’s lawyers will use whatever means they can to delay proceedings for as long as possible in the hope that by the time the appeal is heard he will have won back the presidency. That wouldn’t give him the power to pardon himself (state convictions are beyond presidential power) but he would have succeeded in regaining the White House.

Meanwhile, the former president is already seeing the political upside of criminal status. The boost to his fund-raising — a reported US$53 million haul within just one day of the guilty findings — has wiped out the lead president Joe Biden had enjoyed so far this year. How much of this money will be siphoned off for legal bills or distributed to other candidates through the Republican National Committee remains to be seen.

Trump’s trial also seems to have united the Republican Party as never before. Republicans have lined up to echo his claims of political persecution, with even long-time rivals and those who have sought to keep their distance rallying to his defence. Senate minority leader Mitch McConnell, often a Trump critic, declared that the charges shouldn’t have been brought against him and senator Susan Collins of Maine, a moderate who has pledged not to vote for him in November, denounced the case as politically motivated.

Republican figures like these clearly fear the consequences of speaking out against Trump. When former Maryland governor Larry Hogan — seen as one of the Republicans’ best chances to flip a seat and gain the majority in the Senate — declared that “we must reaffirm what has made this nation great: the rule of law” he was immediately threatened. “You just ended your campaign,” a top Trump campaign adviser responded on social media. Lara Trump, co-chair of the Republican National Committee and Trump’s daughter-in-law, said Hogan “doesn’t deserve the respect” of any Republican for his comments and refused to confirm whether he would receive any party funding for his campaign.

Trump’s mega-donors, the tycoons who defected from his camp after the 6 January riot and the Republicans’ abysmal performance in the 2022 midterm elections, have also been sidling back. No doubt they see Trump’s re-election as a real possibility and are attracted by his perceived pro-business agenda and nervous about his known capacity for vengeance.

Although last week’s conviction upends almost everything about American politics-as-usual, it might not change much in the election campaign. As a convicted felon, Trump can’t own a gun, will be denied a visa to enter a significant number of countries (including Australia) and can’t hold public office or even vote in many states. But there is nothing in the US constitution that prevents him from running for president or assuming the presidency, even if he is in prison.

In normal times the convictions would sharpen the choice between Trump and Biden. After all, no presidential candidate from a major party has ever before sought the nation’s highest office with such a badge of dishonour (although Eugene V. Debs ran from his jail cell on the Socialist Party ticket in 1920 and garnered almost a million votes, or about 3 per cent). But Trump’s pollsters are confident that voters in key states have already made up their minds.

While that is probably true of Trump’s MAGA base, it leaves up for grabs the support of independent voters and those Republicans who didn’t support him in the primaries. A Morning Consult poll shows that 54 per cent of all respondents approve of the decision to convict Trump compared to 34 per cent who disapprove. Forty-nine per cent of independents and 15 per cent of Republicans (but only 8 per cent of self-proclaimed Trump supporters) believe Trump should end his campaign because of the conviction.

And voting intentions? Fifty-six per cent of Republican respondents to a Reuters/Ipsos poll said their vote wouldn’t change, with fully 35 per cent saying they were more inclined to vote for Trump. But 10 per cent of Republicans surveyed said they were less likely to vote for Trump, and 25 per cent of independent voters said the same.

What this polling shows is that the New York trial has mostly influenced undecided voters — a sliver of the electorate that could now exert an outsized impact on a presidential election expected to be decided by a handful of votes in a handful of states. In that light, the potential loss of a tenth of his party’s voters could be much more significant for Trump than the strengthened support of just over a third of Republicans. Much can still change over the next five months, though, and for some voters the upcoming presidential debates could be decisive.

Regardless of whether Trump wins or loses, the damaging impact of his vituperative attacks on the judiciary will likely be lasting. What we have seen in recent years is a relentless attempt by Republicans, led by Trump, to undermine the judicial system. They have spoken out against the Democrats’ alleged weaponisation of the judicial process while ignoring Trump’s own attempts, in power and during the campaign, to do just that.

As president, Trump frequently called on the justice department to investigate individuals he perceived as opponents, especially Hillary Clinton, senior officials within the FBI, and special counsel Robert Mueller. He has repeatedly promised to wreak revenge on his political enemies and has specifically threatened President Biden with FBI raids, investigations, indictments and even jail time. Senators, judges, members of Biden’s family and non-governmental organisations are among his other promised targets.

There’s nothing very subtle about these threats. “I mean, if somebody — if I happen to be president and I see somebody who’s doing well and beating me very badly, I say, ‘Go down and indict them,’” he said in an interview last year. “Mostly what that would be, you know, they would be out of business. They’d be out, they’d be out of the election.”

Republicans in the House of Representatives began planning for retribution in January last year by creating a select subcommittee “on the weaponisation of the federal government.” The subcommittee is proposing to hold a hearing this month looking at “politically motivated prosecutions of federal officials, in particular the recent political prosecution of President Donald Trump by the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office.”

In the Senate, meanwhile, eight Republican senators have pledged to oppose a funding boost for the justice department and won’t vote to confirm the Biden administration’s political and judicial appointees. “Those who turned our judicial system into a political cudgel must be held accountable,” they say.

This vehemency has readily been picked up by the party’s supporters, fuelling concern that the attacks on the judicial system could lead to violence. Already prosecutors, witnesses and jurors have been targeted. Small wonder that Americans have been losing confidence in their judicial system every year since 2020, with confidence dropping to 42 per cent in 2023. Public confidence in both federal and state courts has declined significantly, with more people now viewing them unfavourably as providers of equal justice to all.

As legal scholar Paul M. Collins wrote recently in the Conversation, the judiciary depends on a widespread faith in the rule of law to ensure that the public respects and follows its decisions. In its absence, people are more likely to defy judicial decisions and less likely to cooperate with law enforcement.

The good news is that the New York district attorney’s decision to sue and the court’s finding of guilt highlight that not even Trump is above the law (at least for the moment). The not-so-good news is that those decisions also underscore the fact that the US legal system is far from perfect.

As required by the Constitution, all Supreme Court justices, court of appeals judges and district court judges are nominated by the president and confirmed by the US Senate. Today’s top courts provide a perfect example of what this can mean in practice: during his one-term presidency Trump was able forge a Republican majority not only in the US Supreme Court but also in the circuit courts.

This politicisation extends to the states, each of which has a unique set of guidelines governing how state and local judicial vacancies are filled. Where this is done by gubernatorial decisions or nominations, the usual political partisanship can come into play. In many state and local jurisdictions, officers of the court are also elected in the belief that they should be responsible to the electorate. Five states select all of their judges through elections and thirty-eight states use elections to choose some judges. These elections are increasingly expensive, politicised and dominated by special interest groups.

Spending on these elections reached record highs in recent years. With more than US$37 million spent, April’s Wisconsin Supreme Court race was the most expensive state supreme court election in US history. While technically non-partisan, both candidates in that contest were openly aligned with, and heavily backed by, a political party.

Trump’s accusations of bias are made possible by the fact that New York district attorney Alvin Bragg, who led the Trump prosecution, is an acknowledged Democrat, and Judge Merchan, who presided over the trial, was elected in a very Democratic state. America’s acceptance and even promotion of partisanship in the judicial system, and Trump’s own thoughts about weaponising the system against his enemies, make such claims about legal persecution unsurprising. Europe provides examples of how the political temperature of these selection processes could be reduced.

The grim news could get grimmer. Politicisation and attacks on the judicial system would surely continue apace were Trump to be re-elected. As New York Times columnist Peter Baker has written, the election of a felon to the White House will have many consequences. Given that Trump has survived two impeachments, four criminal indictments, civil judgments for sexual abuse and business fraud, and a felony conviction, it is hard to imagine what institutional deterrents could check his hostility towards the judicial system. •