Most media controversies are fleeting. Often they are about egos, judgement and culture wars. They are remembered only by those directly involved. But some are more resonant, catching deep currents from the past and casting shadows on the present and the future. The dust-up about the ABC’s three-part true crime documentary series Exposed: The Ghost Train Fire is one of these.

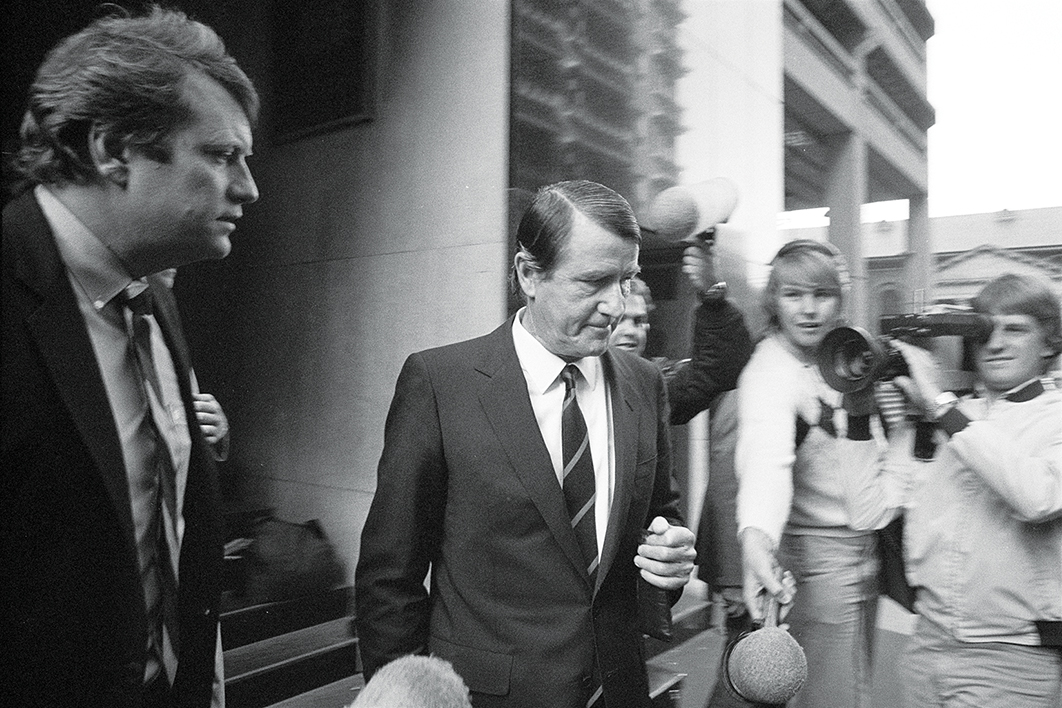

It has picked at sores that have been festering for almost forty years: sores created by the endemic corruption in New South Wales in the 1980s, the unresolved allegations in the so-called “Age tapes” and the record of Neville Wran’s Labor government. As for the present and the future, Exposed represents a small tragedy within the larger tragedy of the 1979 fire in the ghost train at Sydney’s Luna Park, in which six people died.

In my view, Exposed includes some of the best Australian television journalism of recent times. Yet it is being pilloried for faults in the final twenty minutes of its third episode, where the program details, and in places can be understood to be endorsing, an unsubstantiated allegation of corruption against Neville Wran.

The suggestion is that Wran interfered to help crime boss Abe Saffron gain control of the Luna Park site in the wake of arson. Spoiler alert here: I almost entirely agree with the report of the independent editorial review of the program ordered by the ABC board in response to complaints, which was conducted by peerless investigative journalist Chris Masters, a veteran of reporting on NSW corruption, and respected academic Rodney Tiffen.

Masters and Tiffen describe the program as an “outstanding achievement” that used deep, original and rigorous research to make a convincing case that the fire was probably arson, that the original investigation was perverted by corrupt police, and that Saffron may have been involved.

But when it comes to the allegation that Wran was friendly with Saffron and may have intervened on his behalf, Masters and Tiffen believe parts of the program are “misleading” and its references to political corruption “vague, anonymous, and unhelpful.” One of their terms of reference was to ask whether the program “demonstrated open-mindedness to alternative interpretations of events and issues,” and on this they clearly found it wanting.

Let’s talk about the old sores first. Prominent in public life today — and among the program’s most trenchant critics — are people who built their early careers during the decade, 1976–86, in which Neville Wran was premier of New South Wales. They are deeply invested in how history judges those times.

Journalists, too, put their careers on the line back then. Watergate was still a recent memory, and it was much easier to see journalism as an honourable, even heroic profession.

I was a junior journalist in the Age newsroom when Bob Bottom, a journalistic refugee from Sydney, arrived in 1984 in a cloud of glamour, righteousness and zealotry. He carried with him what became known as the Age tapes, which were alleged to contain evidence of corrupt activity by High Court judge Lionel Murphy. That the Age published this material — drawn from illegal phone intercepts by NSW police — was controversial at the time and remains so.

I remember the drunken post-mortems and the anguish when the parliamentary inquiry into allegations of misbehaviour by Murphy — which also involved allegations about Wran — was closed down because of Murphy’s terminal cancer. The records of the investigation were sealed for thirty years, and released in 2017.

It is hard, now, to convey the atmosphere of those times. A raft of royal commissions and corruption inquiries in six states in the 1980s and early 90s, many prompted by excellent journalism (much by Chris Masters) exposed corruption within state governments and aired allegations of federal significance. But among some of the journalists, the zeal was sometimes excessive, and the shades of grey too often depicted as black and white.

A fuller explanation of the times, and what can and can’t be said about the Wran government and corruption, is in an essay by Rodney Tiffen published by Inside Story earlier this week, given extra punch because of its author’s work on the ABC review.

Tiffen gives little comfort to Wran’s boosters and defenders, who have been among the program’s chief critics. While confirming that there is “no persuasive evidence” that Wran was corrupt in the sense of personal financial gain, he also lays out how corruption grew on Wran’s watch, and how he used government patronage for political advantage. In particular, Wran did favours for media barons — Rupert Murdoch chief among them. Tiffen sees Wran as a transitional figure between the rampant and established corruption of his predecessor, Robert Askin, and the reforms of the 1990s, including the creation of the Independent Commission Against Corruption.

The issues here — the slippery connections between the unscrupulous use of power for political advantage, the importance of ICAC, the enmeshment of media with government and power, and journalists’ roles on both sides of the corruption fight — could hardly be more relevant to our own times.

So much for the currents and the shadows. What of the program itself?

One of the chief critics of the ABC and Exposed has been Troy Bramston, a senior writer with the Australian. Bramston, in my view, makes some fair points but over-eggs his pudding. He has said the Luna Park fire was probably caused by accident rather than arson. How he can feel so secure in that conclusion after viewing episode two of Exposed is beyond me. Here, Bramston betrays biases and blind spots of his own.

Bramston and others have also suggested that the media — and the ABC in particular — should not report unsubstantiated allegations, including the allegations against Wran. I think that’s ridiculous. As the ABC editorial policies say, and surely all journalists would assert, publishing allegations “in the public interest is a core function of the media in a free society.” But of course it should be done after careful judgement, with context, clarity and balance.

The claim that the ABC should not have broadcast the allegation against Wran is particularly weird because it was already public. It can be found in the records of the parliamentary inquiry released in 2017, where it features as “Allegation 28.” It rested on police officers’ memories of what was contained in since-destroyed transcripts of the Age tapes. Exposed found one of those officers, Paul Egge, and interviewed him, and he stood by his recollection.

When the documents, including Allegation 28, were released in 2017, virtually all media outlets, including the Australian, reported them, despite the fact that they were untested allegations. Quite right too. This was of historical significance. It would have been wrong for Exposed not to deal with this material.

On Tuesday this week, the chief reporter on Exposed, Caro Meldrum-Hanna, tweeted screen shots of some of this coverage. “This morning,” she wrote, “I’m looking forward to an avalanche of complaints about all the previous coverage by all other media outlets who reported the exact same allegation & Paul Egge’s evidence (but without contemporary interviews with him or other relevant police and judicial witnesses).”

She has a point, but there is a difference between contemporaneous reportage of a document release and the way Exposed wove those same allegations into its narrative. The core problem with those last twenty minutes of Exposed, in my view, is not the material that was run but rather that more needed to be added. The allegation needed clearer signposting and contextualisation.

The suggested narrative has holes in it. It isn’t clear how Abe Saffron benefited from the Luna Park lease — if he did. There is no firm evidence that Wran intervened in the tender process, and some evidence that goes the other way. The allegation that Wran was “pally” with Saffron rests on the word of just one witness without corroboration. These things could and should have been clearly stated, perhaps in the conversations between the reporters that are used throughout Exposed as a narrative device.

A key graphic, screened twice in those final twenty minutes, depicts the substance of Allegation 28 as a hard red line linking Saffron and Wran. But even if the transcript Egge remembers still existed and the ABC had a copy, it would still amount to hearsay evidence — what others were saying about Wran — rather than direct evidence.

All these things should have been more clearly declared in the program. Other points of view could have been included — perhaps from some of the former ministers and staffers who have been among Exposed’s critics. Other material in the Age tapes that suggests Wran wasn’t corrupt could have been mentioned.

The ABC claims the program was not adopting the allegation against Wran, merely reporting it. And it is true that the crucial passage is littered with the word “allegation.” But other material pulls against this, including highly suggestive yet evidence-free comments from interview subjects, such as “there must have been something in it for Wran.”

As Tiffen and Masters conclude, “The series offers a penetrating and precise account of police corruption, judicial shortcomings and probes behind the façade of commercial interests. In contrast, its references to political corruption remain vague, anonymous, and unhelpful… The cumulative effect… left the reviewers with a strong impression the program concluded Wran was complicit… The program makers have not succeeded in framing a conclusion that plainly stated their position.”

The tragedy is that all these things could have been fixed with relatively small changes. Had that been done, Exposed would probably still have been attacked, but it would have been entirely defensible.

And so we come to another shadow on the present. I don’t blame the program makers for the muddiness and the overreach. Anyone who has worked for years on an investigation like this grows too close to the material, and then defensive of it. That is why the ABC has its rigorous processes of upward referral, and program review and sign-off.

In this case, in the case of those last twenty minutes, those processes failed. Hindsight is a wonderful thing, of course. But I nevertheless find it hard to believe that these issues were invisible to the executives who would have reviewed the content.

Add to this failure an unimpressive appearance before Senate estimates by ABC managing director David Anderson and editorial director Craig McMurtrie, in which McMurtrie suggested that the allegation against Wran didn’t need to be backed up more thoroughly because it was not the focus of the series.

And add to that the way the ABC dealt with the Masters and Tiffen report. First, the corporate communications team released ABC management’s response selectively: to the Nine newspapers and the Guardian, as I understand it, but not to the Australian, which had done most reporting on the affair. And then it only released the Masters–Tiffen report itself, quietly, about twenty hours later.

This was a classic spin manoeuvre by the ABC: getting your own version out there first to try to frame the coverage. We expect it of politicians but not of a publicly funded media organisation.

Having said all that, I suspect the legacy of Exposed will not be the controversy about its final minutes. The coroner has indicated a new inquest may be held as the result of evidence in the program. Exposed certainly makes a compelling case that one is needed. If that happens, this is what Exposed will be chiefly remembered for.

Other sores will continue to fester, though. The lesson here is that failing to combat allegations of corruption — both in the specific, criminal sense and in the broader political sense — is a flaw with generational longevity. •

The publication of this article was supported by a grant from the Judith Neilson Institute for Journalism and Ideas.