When Bill Leak died suddenly in March 2017, two days after the launch of his fourth cartoon collection, Trigger Warning, it seemed you could choose between two positions. Either he was the villainous creator of “that racist cartoon” of an Aboriginal father enquiring as to the name of his son, or he was “our dead king,” murdered by the repressive forces of political correctness. Fred Pawle’s biography of this giant of Australian political cartooning veers towards the latter view, as you might expect in a book sponsored by the Institute of Public Affairs. But it is a much richer account of a passionate life than either caricature could sponsor.

Pawle is a loyal friend to Leak, but not a hagiographer. He does not downplay the alcohol, the women, the reckless personal life or the periods of depression. His Leak is a Romantic hero — flawed, generous, brilliant and sometimes haunted. I grant all this — Leak was one of the greatest Australian cartoonists of the last half-century, and the best visual artist among them. No one learned to use colour so well when it appeared in newspapers in the 1990s, and no one has a more incisive line for caricature. If there is such a thing as a larrikin line in Australian cartooning, he had it.

Like most cartoonists, at least those in the baby boomer generation, Leak learned mainly on the job. He went to various state schools in the country and then Sydney as his father rose through the ranks as a postmaster. He was a bright and flamboyant individualist, the class clown and raconteur rather than a leader of the football team. In his later years at school he began drinking, and he only ever got the drink under control sporadically for the rest of his life. Pawle suggests that, for the teenage Leak, “the torment associated with overactive creativity was beginning to impose itself.”

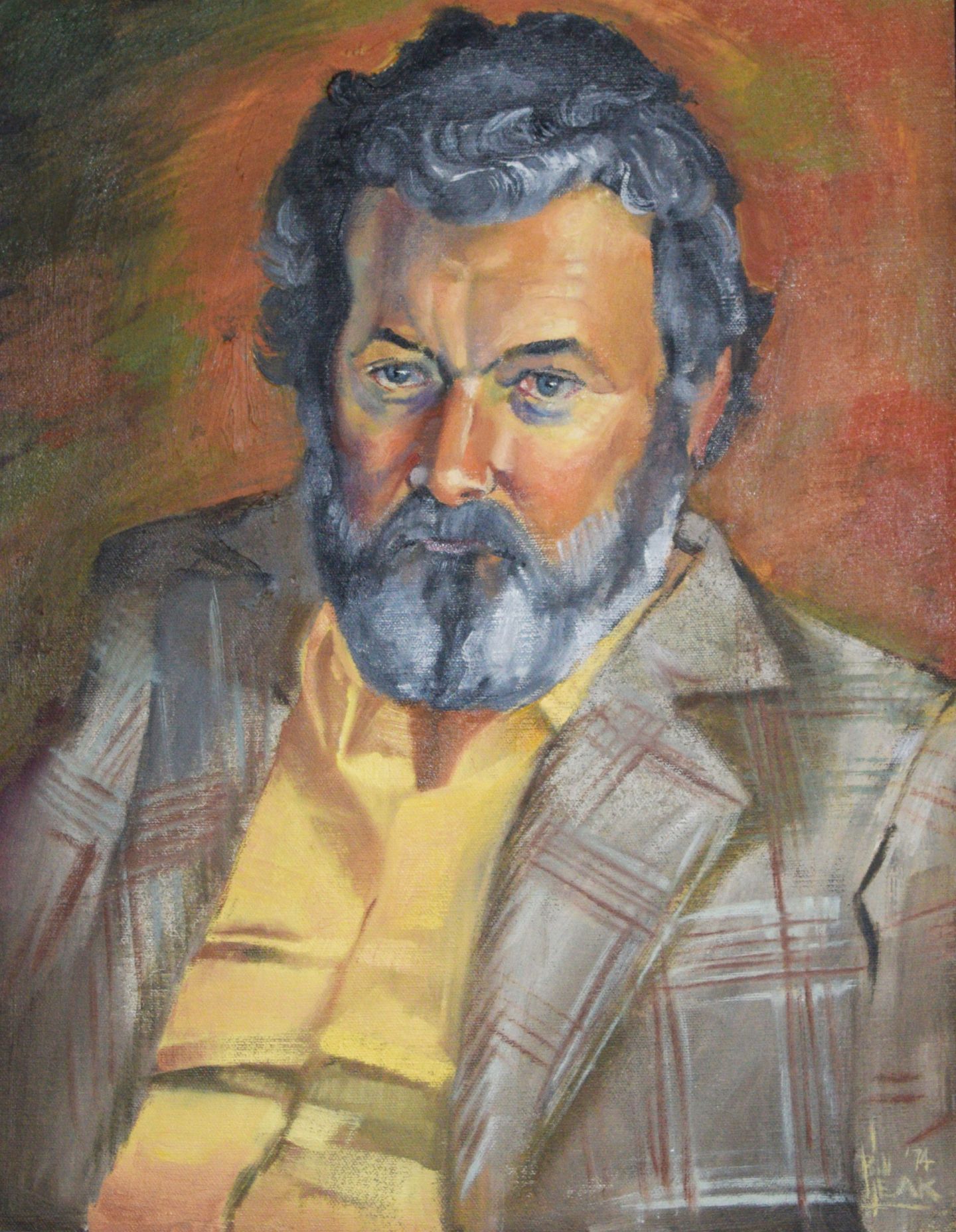

He qualified for university, but went to art school instead. From there, he took to the road in pursuit of his muse as a painter, first around Australia, and then to England and Germany. He was wrestling with paint as a deep craft rather than dabbling in conceptual art or seeking an internship in the creative industries. It seems a long time ago, and it bespoke a mildly conservative view of the nature of art even then.

He became and remained throughout his career a successful portraitist, perennially snubbed by the judges of the Archibald Prize. This is a middle path in the art world — serious but not experimental — and Leak could easily have made a living flattering the great and good in oils rather than attacking them in newsprint. Once he sold some cartoons to the Bulletin in 1983, however, he was hooked, by both the immediacy of print and the more regular pay in that distant era of numerous staff artists and good money for freelancers.

Frustrated ambition: Bill Leak’s portrait of his father Reg (1974).

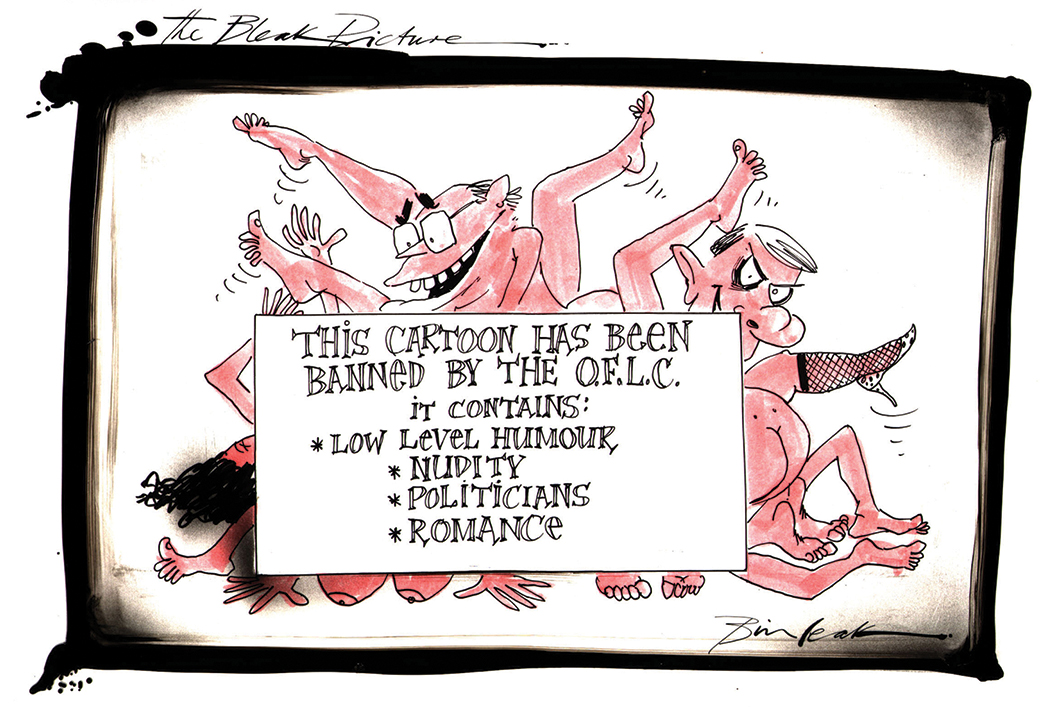

He moved into the extraordinary Fairfax stable of black-and-white artists in Sydney in the 1980s, primarily drawing caricatures to accompany articles rather than as an editorial cartoonist. His cartoons didn’t articulate political views so much as display an anti-authoritarian attitude and a killer style. Larrikin anti-authoritarianism in the long wake of the Menzies years was still straightforwardly of the left, and that is where Leak sat, with a large majority of cartoonists. For his vigour and brilliance, he started being awarded Walkley and Stanley awards by his media and cartooning colleagues while the Archibald judges stayed annoyingly aloof.

In 1994 Paul Kelly, arguably the most sombre presence of the last half-century in Australian journalism, decided the paper he edited, the Australian, needed Bill Leak and made him an offer too good to refuse. That he was clearly associated with the bohemian left was not a problem then, as it might be now in more battlemented times. The nineties were a great era for his cartooning, and he provoked the Howard government scabrously. The story about an unpublished cartoon faxed around Canberra of John Howard, Bill Clinton and submissive sexual postures is still wild enough to require euphemism.

In attack and style, he could have stridden into the artists’ room at Smith’s Weekly in the 1920s and taken a desk, wherefrom to attack pompous fools and self-serving knaves who were bilking ordinary diggers. He could work ideas with wit and humour, but he was a larrikin individualist at heart, and best at playing the man rather than dancing to any abstract set of ideas. You can see this in his portraits also. Moreover, some of the chapters of his life would not look out of place in Lennie Lower’s Rabelaisian Here’s Luck (1929). He comes from the print-era world of newspapermen (and they were overwhelmingly men) who worked frantically to meet deadlines and then drank frantically to recover from them.

He never really built a recognisable political philosophy of the kind visible in Bruce Petty, Bill Mitchell or Cathy Wilcox. When John Howard was in power and subservient to the United States, he had him raising funds for Brown-Nose Day. When Kevin Rudd won the 2007 election he quickly turned from Tintin into Narcissus. If you look at a lot of cartoons, Leak was clearly an equal opportunity offender. But it seems to me that, during his last decade, fewer of his cartoons achieved what John Dryden admired about satire in 1700: “there is still a vast difference betwixt the slovenly butchering of a man, and the fineness of a stroke that separates the head from the body and leaves it standing in its place.” But that may tell you more about me than it does about Leak’s achievement in that time — anyone who sets up to be an objective judge of satire is a charlatan. We laugh most when we already agree.

When his friends and his newspaper changed, the ideological tenor of his cartooning changed a bit also, but the ground had shifted for everyone by then. There was less middle ground, and it is not a good satirist’s job to go looking for it.

People who care about Leak’s art should enjoy Pawle’s sympathetic but unflinching account of his complicated family and personal life. His passions were difficult for anyone to live with for long, his need for peak experiences too great. His last years, constrained by death threats prompted by his anti-Islamist cartoons, were also his years of greatest domestic security. He married Rewadee “Goong” Phitnak and was thoroughly reconciled with his sons Johannes and Jasper, from his first marriage to Astrid Wiegand. After the death threats and the life-threatening fall from John Singleton’s balcony, he reduced his socialising and lived on the Central Coast north of Sydney. Consequently, he seldom went to the newsroom and relied for sounding boards on those, especially at the Australian, who were most loyal to him. Despite a voracious appetite for company, he became a bit isolated.

People of the left like to say that Leak’s cartooning changed after the fall at Singleton’s, as if only brain damage can explain opinions they find unpalatable. It was much more complicated than that. Only pathologise conduct when you’ve first tried hard to take it seriously. Pawle’s book shows clearly that Leak cared deeply about the right to free speech, and that this viewpoint was not simply a cynical shield for racism, neoliberalism and the other Halloween dolls of progressive critique.

Of course, being serious doesn’t make him right in all his provocations — freedom of speech is not the right to dominate the conversation, let alone to be heard and obeyed. But deploring things you disagree with is (almost) always a healthier option than patronising them — let alone legislating for pre-publication licensing or using post-publication legal censure to punish individuals and chill debate. Where power has access to really effective means of censorship, citizens get “protected” from far too many things that should see the light of day.

So what of the cartoon that was brought before the Human Rights Commission under section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act? In my opinion, it was being arraigned in the wrong place. No one needs to admire it, but it was far from the racist equivalent of the “shouting fire in a crowded theatre” test so often referred to in debates and legal cases about legitimate constraints on speech. Like all political cartoons, it deployed stereotypes for compact communication, and the subject matter involved race, so the stereotypes were racial. This entails obvious risk of offence, but is silencing really a valid response to all complicated images and issues?

Pawle shows convincingly that Leak was not deliberately expressing a racist purpose in this cartoon. He worked hard on it over a couple of days and was not aware it would be published on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children’s Day. He had a good record on race in his personal life and his cartooning, even if his deep attachment to individualism made it hard for him to see or value more communal forms of belonging. Even if you think the cartoon too easily misinterpreted by readers who wanted to draw racist conclusions (as I do), that is grounds for criticism, not for sending in the lawyers.

Barry Humphries, the eternal provocateur and genius of Australian satire, saw in Leak a fellow spirit. He launched Trigger Warning as Sir Les Patterson and contributes an introduction in his own voice to this book. As you’d expect, it is fey, brilliant, and worth the price of the book on its own. His most critical point (in all senses of the word critical) absolutely nails the abiding force of Leak’s work. Talking of the 2016 cartoon, he criticises “the Australian Humour Police who have failed totally to understand the ferocity and compassion of Leak’s satire.”

Ferocity and compassion are what you want in your great cartoonists. It is not their job to comfort us. •