When national elections are held around this planet, they usually involve bits of paper, as they do in this country. And a big majority of countries use the Australian Ballot. Daylight is next, followed by the French Ballot.

(Exact numbers don’t exist, but the Ace Project’s imperfect database says it’s about 60 per cent Australian Ballot and 20 per cent French Ballot, with the rest being combinations, permutations, something totally different, or paper-free.)

What’s the difference between the Australian and French systems?

Under the Australian Ballot, the elector chooses a candidate (or candidates, or a party or parties) from among the ones listed on a single piece of paper — as we do, for example at federal elections, on a ballot paper for each house of parliament.

Under the French Ballot, voters choose a ballot paper from several piles, each representing a party or candidate. Their choice typically goes into an envelope so no one can identify it as they make their way to the ballot box. No pen or pencil required.

Both versions have their origins in open voting — that is, non-secret voting — around two centuries ago. Back then, electors brought along bits of paper on which they had already written not only the name of the candidate they were voting for but also their own name, address and qualifications to vote.

Open voting had its problems, and so some places — including France, Switzerland, Belgium and a few American states — introduced the secret ballot. It still involved bringing along a piece of paper and putting it in a ballot box, but electors only needed to identify whom they were voting for. They might write it themselves, or cut it out of a newspaper, or take the paper from a candidate’s agent on the way in. Candidates often had chosen colours to represent them, and these ballot papers would be that colour. So it wasn’t very secret in practice; secrecy was optional. If you’re trying to eliminate bribery or coercion, that was quite a flaw.

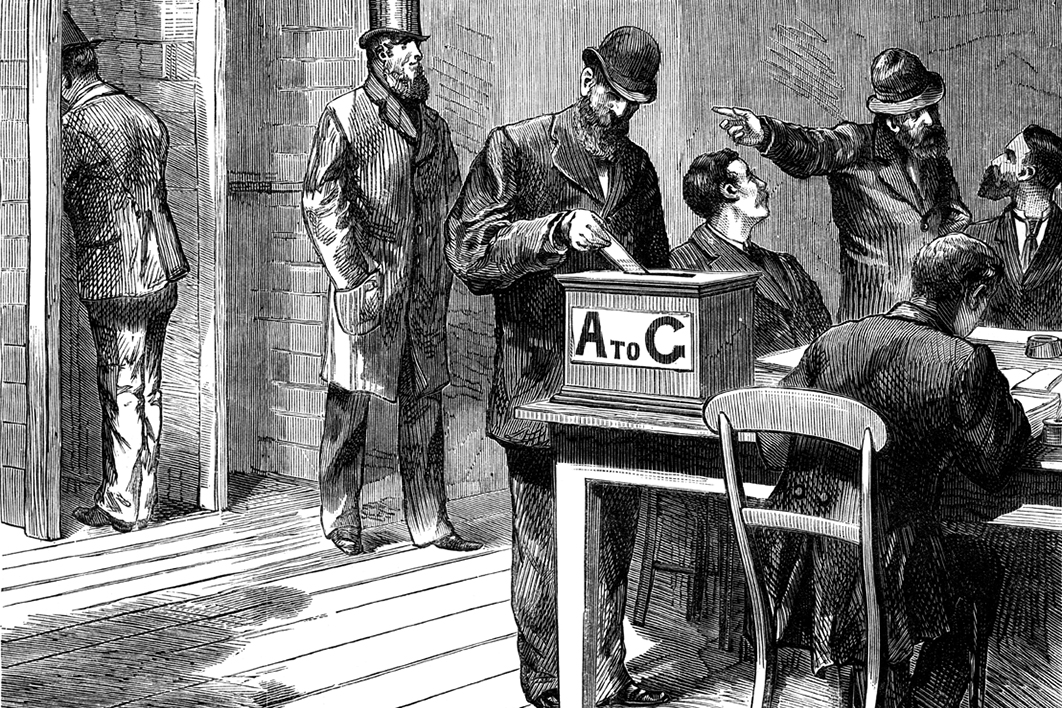

And it led, at least in France, to rather rowdy election days, as candidates’ agents loitered outside polling places to thrust their ballot into voters’ hands, and follow them in, sometimes all the way to the ballot box, to ensure they put that ballot, and only that ballot, in the box.

And so, in 1856, we ingenious Australians invented a new way of voting to disincentivise such rowdy behaviour and eliminate fraud and coercion. We did this by the simple expedient of making it impossible for people to prove how they had voted. Henceforth, the government would supply ballot papers containing candidates’ names. Electors would arrive empty-handed, be given a ballot paper, go to a compartment and make their mark, fold the paper and put it in the ballot box.

It was very labour-intensive and burdensome on the public purse, and back in England many rolled their eyes at this typical colonial extravagance. But it eventually became the most common way of voting around the world.

Still, the French stubbornly persisted with their system. But it slowly evolved, and eventually — perhaps borrowing from Australia — the government began supplying the ballot papers in this system as well, though it still involved a different piece of paper for each candidate. Eventually the French brought in secret voting compartments, too — with curtains. Making them much more secret than ours.

The French system is used in a small number of countries today, including France. Many ballot papers are printed, and lots are thrown away afterwards.

Some countries have gone for a combination of systems: a ballot paper for each party, onto which the voter makes a written choice among individual candidates. In Sweden they use the French system but choose the ballot paper out in the open. That’s pretty weird and not very secret at all.

The French system predominates in its former colonies, for example in Africa (although over the last decade or so some have moved to the Australian Ballot). Systems in a few other countries have evolved separately to resemble the French. (If it involves a curtain, it probably came from France.) Argentina has hardly evolved at all: the parties and candidates still supply the ballot papers.

I used to say that the very idea of a government-supplied voting paper with candidates’ names originated in Australia. It was very Australian, given our talent for bureaucracy and all that.

But last year I learnt from two experts on France and its elections, Malcolm and Tom Crook, that during the French revolution a French lawyer and academic named Jacques-Vincent Delacroix suggested this method for voting on referendums:

Each voter will be given a printed ballot paper, bearing propositions. Each voter to whom this bulletin is given will go into a designated space, divided into several compartments, where, without being seen, he will write “yes” or “no” after each proposal. He will then fold the paper, stamp it with the national seal and put it in a closed box.

Sound familiar? Maybe, on the other side of the world, six decades later, those Australian reformers had heard of this idea.

So should we perhaps call it the Delacroix Ballot? •