THIS IS a story about an Englishman, an Irishman and the strange career of the Australian conscience. It begins at the top of a rocky hill in Central Australia, at sunset, on or about Friday 20 July 1894. The Englishman and the Irishman have just met, and there is romance in the air. They are in a magical place at a magical time of day. Each is an exotic to the other. Baldwin Spencer, the Englishman, is a professor. Frank Gillen, the Irishman, is a postmaster. Spencer, aged thirty-five, is the son of a wealthy, protestant industrialist from Manchester and a relatively recent immigrant, now resident in Melbourne. Gillen, thirty-eight, was conceived in Ireland but born in Australia to Catholic store-keepers in a South Australian country town. Spencer is an Oxford graduate, Gillen an autodidact. Gillen is tending to the portly while Spencer is slight; each sports a big droopy moustache. Both are charming and gregarious, love a pipe, a whisky and a yarn, and they follow politics and world affairs with a nice balance of agreement and dispute. Both are of liberal mind, anti-clerical, and pro the development of the Australian continent and an Australian nation, but Baldwin is an Empire man and for Capital, while Frank is an ardent Home Ruler with Socialistic tendencies. Both are modern men. And both are utterly fascinated by the Aborigines. They would become the most famous – and infamous – duo in the history of Australian anthropology.

By the time Frank Gillen met Baldwin Spencer he had been in Central Australia for almost exactly half of his life, but his encounter with the Aborigines began before he even got there. Early in 1874, when he was an eighteen-year-old operator at the Adelaide terminus of the brand-new Overland Telegraph Line, Gillen was the recipient of a grim message from the Barrow Creek repeater station, nearly 1200 miles north in the wilds of Central Australia. Two of the station’s staff had just been speared by “treacherous natives” while taking the evening air and listening to one of their number play the violin. Over the hours that followed the young Gillen played a part in a scene that might have come from Rider Haggard. He was the intermediary in poignant exchanges between the dying stationmaster in Barrow Creek and his wife in the Adelaide GPO. Gillen was vehement in support of the vigilante squad of linesmen from the stations up and down the Line who rode out and slaughtered dozens of men, women and children.

Just over a year later Gillen was on his way north to take up a position at another of the Line’s remote stations, and he kept a diary. Like the hero of the film Dances with Wolves, Gillen advances wide-eyed and excited through succeeding layers of the frontier to its very edge, the point of that unfathomable moment of First Contact. Our sense of the young man’s deepening wonder is heightened by the way his journey slows as it advances, commencing at speed in the train, then moving to stage coach to buggy to horseback. His measure of progress through the frontier, half-consciously used, is the appearance of the Aborigines. Early on he sees layabouts, beggars, half-castes and drunkards. Later there are shepherds and trackers, much valued by pastoralists and policemen. Seven weeks after leaving Adelaide, now more than 600 miles away, he arrives at Peake, generally regarded at that time as the point beyond which firearms should always be carried. “There are dozens of Niggers about here, very few of them possess the luxury of an article of Clothing…,” he reports. “They live principally on Snakes, Lizards and herbage and all look in excellent Condition.” At every way station Gillen makes a point of visiting the Natives “for a yabber” and to build up his word lists, one of Aboriginal names, the other of more than a hundred terms and phrases arranged in alphabetical order: Al-lelia (Grass), Apra (Gum tree), Al-linga (A long distance), Anima (Sit down).

The absence of animosity toward the Aborigines in Gillen’s diary is striking. It might even be that its boisterous, jocular comments about the Aborigines and their squalid circumstances betray a young man’s moral unease. Whatever the case there is no doubt that over the succeeding years Gillen’s comprehension of the Aborigines and their experience of the whitefellas took a place in his mind at least as prominent as his earlier outrage at their “treachery.” The Aborigines were a familiar part of life on the Line’s repeater stations, first as potential adversaries, then as mendicants. The Charlotte Waters station (south of Alice Springs), where Gillen spent most of his first decade or so in Central Australia, was designed to serve as a fort but soon became an almshouse. Gillen made the most of daily interactions with the local people to get to know them and their baffling ways. So far did his sympathies grow that in 1891, not long before meeting Baldwin Spencer, he charged the notoriously violent policeman William Willshire with the murder of two Aboriginal men. Willshire’s conduct was not so different from that which a couple of decades earlier Gillen had emphatically supported.

By then Frank Gillen was officer in charge of the Alice Springs repeater station and therefore a justice of the peace, local magistrate and Sub-Protector of Aborigines. Sitting on top of the rocky hill with his new mate Baldwin Spencer, Gillen was master of all that he surveyed, the most senior civil servant between Port Augusta, 750 miles to the south, and Darwin, 1000 miles north. Down below was his redoubt, the telegraph station, “quite a little settlement in itself [as he and Spencer wrote some years later] with its operating room where day and night the machines are ticking ceaselessly: separate quarters for the officers in charge; dining, mess and living rooms for the operators, four in number; rooms for the line men; battery room, shoeing forge, blacksmith’s shop and all other essentials of a little settlement that must be able to provide for many a sudden emergency…” Gillen was referred to by his mates as His Catholic Majesty, the Pontiff, the Amir of Alice Springs.

Baldwin Spencer, too, was living an adventurous life. A decade earlier, as a twenty-six-year-old, a recent Oxford graduate and a newly married man, he had set sail for the Antipodes, 12,000 miles away, to take up the post of professor of biology at the University of Melbourne. Hyperactive, enchanted by “so much that is new” in the strange continent (his phrase, later borrowed to become the title of his biography), he was soon regarded as an inspired appointment, likely to return in the not-too-distant future to a chair at Oxford. But a trip to Central Australia, and a new friendship, would change all that.

As a star of Victoria’s scientific firmament Spencer had been nominated by the colony’s premier as its representative on the Horn Scientific Expedition to Central Australia, funded by the eponymous William Horn, a wealthy South Australian pastoralist. Spencer was the expedition’s biologist, not its anthropologist, but “biology” then was a broad church, and on his first trip deep into the continent’s interior Spencer simply couldn’t help himself. Like the youthful Frank Gillen two decades earlier, he was scarcely off the train at its terminus at Oodnadatta, 330 miles south of Alice Springs, before he began taking photographs and making notes on the Natives. By the time the expedition’s camels had padded all the way to Alice Springs, on a route that included a circumnavigation of the western MacDonnell Ranges, he was as interested in the Aborigines as in flora and fauna.

Most members of the Horn expedition headed for home just a few days after reaching the Alice Springs telegraph station, but Spencer did not. He stayed for nearly three weeks to complete his collections and investigations. But he also spent hours on end exploring Frank Gillen’s impressive store of knowledge of the Natives. It was later said that Baldwin Spencer’s greatest discovery was Frank Gillen. The converse was also true. When in 1912 Frank Gillen died of a debilitating neurological disorder Spencer wrote to Gillen’s widow the kind of letter we might all hope to write at such a time. “As I often told him,” Spencer told Amelia Gillen, “my meeting him at Alice Springs made all the difference to my life and I like to think that it made, as he told me also, a great difference to his… No one ever had a better friend and comrade than he was and I look back on his friendship as one of the greatest privileges and blessings of my life.”

SPENCER was scarcely back in Melbourne from the three-week stay in Alice Springs before the letters began to flow. (Sadly, Gillen’s widow burned Spencer’s letters to Gillen, but from Gillen’s side we can follow the course and sense the intensity of their correspondence.) “As I sit here in the old ochre smelling den, which you know so well,” says Gillen in his first letter, “I can imagine you demonstrating the anatomy of a Cockroach to a lot of Callow Youth… do you, I wonder, ever wish that you could transport yourself to the wilds of the McDonnells [sic]. I often wish that you could, I missed you very much indeed…”

The centre of their correspondence was, of course, the Aborigines, and it was therefore semi-illicit. Spencer had not been appointed to the Horn expedition to study Aborigines – that was the job of one of his colleagues, Dr Edward Stirling – and so Spencer came perilously close to treading on an academic colleague’s turf. The problem was compounded by the fact that Spencer was editor of the expedition’s reports, and therefore in frequent contact with Stirling. Gillen, too, was constrained by the fact of Stirling, or was meant to be anyway. He had established what was in effect an exclusive-provider arrangement with Stirling several years before the Horn expedition had turned up in Alice Springs, sending him information and artefacts. What’s more, Gillen had undertaken to give Stirling new material to help fill out his findings from Horn.

As the Gillen–Spencer correspondence flourished their respective relationships with Stirling frayed. As in a bedroom farce, Spencer and Gillen tried to tiptoe their way around Stirling’s room but left behind a trail of letters, chance encounters and protestations of innocence. Gillen’s long, excited letters to Spencer suggest that he was the motive force in the friendship. Gillen badly wanted to make a name for himself, not so much through wealth (although he kept plunging, vainly, on mining shares) or power (although he flirted with going into politics) as through recognition. He really, really wanted a place in the sun. Spencer must have looked like his big chance.

For his part Spencer was well embarked on a distinguished career as a biologist, but he also knew that mapping the evolution of homo sapiens was one of the hottest intellectual fields in the English-speaking world. While still a student at Oxford he had attended the first lectures on anthropology ever given in Britain, and subsequently got a vacation job helping the eminent E.B. Tylor set up what was to become one of the world’s greatest anthropological museums, the Pitt Rivers. On the eve of Spencer’s departure for Australia soon after, Tylor wrote to suggest that he might “come into contact with interesting questions of local Anthropology… [and] do valuable work in this line as well as in your regular biological work.” Soon after he arrived in Melbourne Spencer sought out the leading “ethnologists” Alfred Howitt and Lorimer Fison. He realised that the findings of these and other ethnologists could be placed in the vast panorama unveiled by Charles Darwin. “Australia is the present home and refuge of creatures, often crude and quaint, that have elsewhere passed away and given place to higher forms…” he later wrote. “Just as the platypus laying its eggs and feebly suckling its young, reveals a mammal in the making, so does the Aboriginal show us, at least in broad outline, what early man must have been like…”

Within six months of Spencer’s stay in Alice, Spencer had arranged for Gillen to visit Melbourne, and Gillen had sworn not to give Stirling his newest, most exciting insights. In Melbourne Gillen stayed with the Spencers and was introduced by Spencer to Howitt and Fison. Back in Alice from Melbourne, floating, Gillen wrote to Spencer, telling him that it would be “a calamity to me if your interest in the subject cooled down.” A month later, in December 1895, Spencer had committed to working with Gillen. They would write a book together.

Then Gillen got lucky all over again. He’d heard of a big cycle of ceremonies known as the “Engwura,” never seen by white men. By the mid 1890s the decimation of the Aboriginal population in the Alice Springs area by violence, disease, malnutrition and simple demoralisation was such that it seemed that the great festivals might never be held again. Could he turn it on for his friend, and their book? Gillen’s standing among the Arunta (Arrente) had been greatly boosted by his efforts to have Willshire brought to justice. What’s more, he was in a position to offer the food and water needed for an extended gathering of 200 or more people. By mid 1896 it was agreed that Gillen and Spencer (artfully elevated by Gillen to the status of his “brother”) would observe and record the hitherto secret ceremonies to be conducted later in the year.

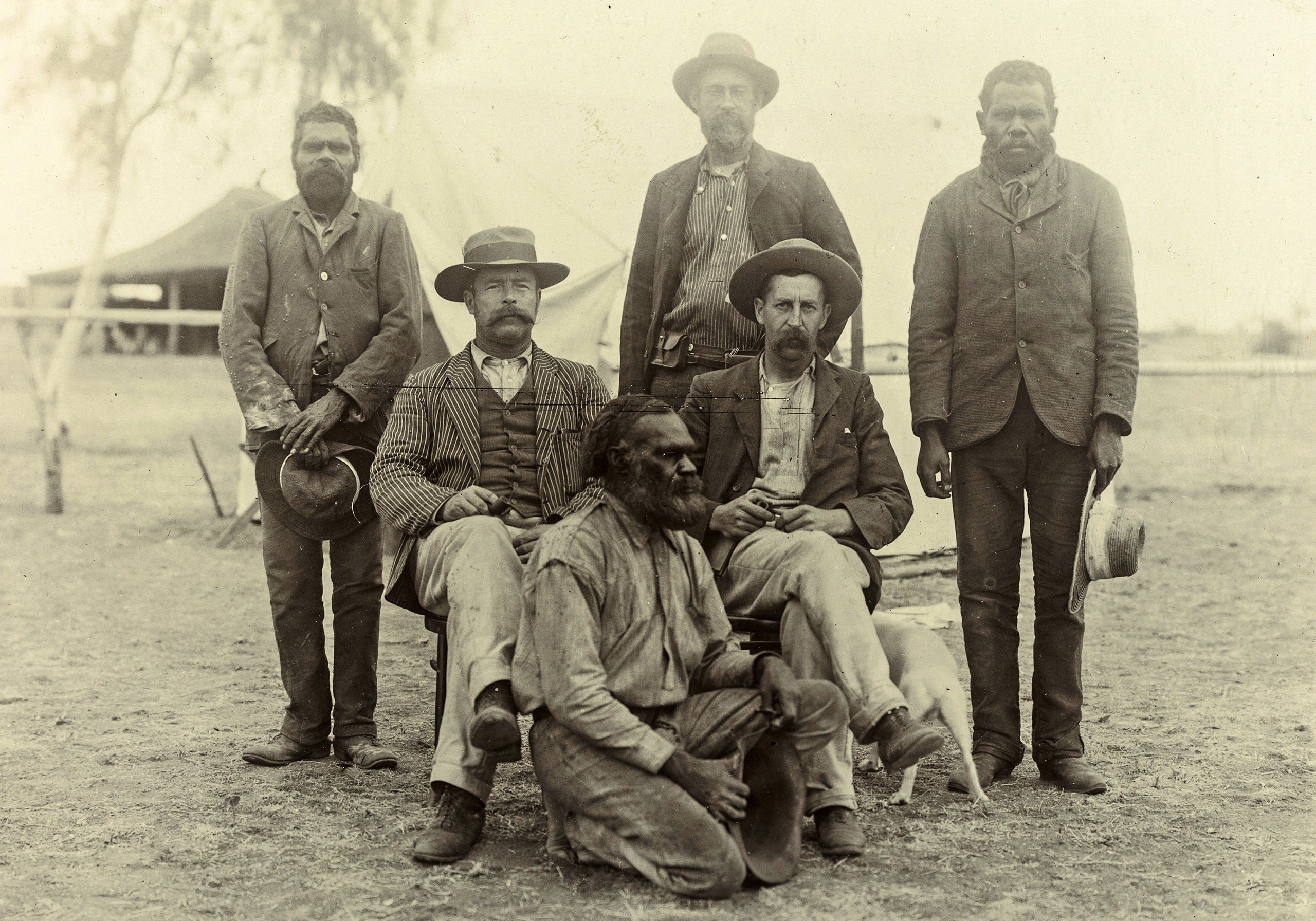

Gillen didn’t know what he was letting himself in for. It could go for a week, he told Spencer. In the event the ceremonies started before Spencer arrived in early November and continued non-stop, with up to six ceremonies a day throughout his eight-week stay. It was still not done when he left in January. Because they couldn’t figure out what would happen when, and for fear of missing something, they constructed a rough bough shelter on one side of the ceremonial ground, a few hundred yards from the telegraph station, and camped there for the duration. They met frequently with the men who did know what would happen when. Photographs of the two white and thirteen black patriarchs present one of those images in which at one moment the Aborigines look to be completely familiar and at the next completely Other. There they are, for all the world a conference committee (an academic conference committee in fact) exuding the authority of great learning, but these are also men who, by chanting exactly the right words in exactly the right sequences, by wearing the right designs and decorations, by leading their fellow-initiates through the necessary gestures, cries and steps, joined the ancestral beings with whom we and the world began.

The Engwura made great copy. Spencer and Gillen’s account of it takes up 150 of their book’s 670 pages. But content wasn’t the main thing. Other white men, including earlier ethnologists, had described various ceremonies, some in original condition, some reconstituted, but no one had ever been present at such a sustained revelation of the Aboriginal spiritual world, vast, intricate, deadly secret. Indeed no one had ever done such intensive and such privileged “fieldwork,” as their collaboration with the Arunta would now be termed. It seems to have been an unforgettable experience for the two men, Gillen particularly. After the book was published and the day before he left Central Australia for a posting Down South, Gillen sent Spencer the last of his many missives from Alice, a telegram: “Leaving for Adelaide tomorrow, taking last look at Engwura ground today. Fixing site for Erection Stone pillar there.” (The pillar, if erected, has not survived.)

The Engwura experience sustained an extravagant burst of creative energy. Gillen’s frenzy of activity and excitement was the subject of much acerbic banter from mates of Gillen’s who had in turn become correspondents of Spencer’s. “Gillen I never hear from,” one wrote to Spencer, “[H]e is working like a Trojan, night and day, at his Ethnological notes. Rumour has it that he recently got up in his Sleep and adjourned to the washhouse from which there presently came a sound of chanting accompanied with vigorous stamping of feet: and on the astonished Night Operator going to see what was the matter, he found the Pontiff, artistically decorated… corroboreeing away like an Aroondah warrior!”

Gillen’s letters to Spencer were running to forty pages and 6000 words, most without the benefit of paragraphing or punctuation, and he sent long field reports as well. We’re unravelling their systems, he would crow. We’re daily getting deeper into their mysteries! As his ambitions soared so did his anxiety. What if Stirling or any one of a number of rival ethnologists cracked it first? No, they can’t, they won’t be able to! Just look at this table of relationships! I’m getting evidence from far afield (which meant from colleagues up and down the Line). They’ll never figure out the eight-class version of the kinship system. It’s so hard to know when you’ve really got to the bottom of things. Poor old Stirling didn’t even know who’d been subincised and who not.

Spencer began drafting the book as soon as he was back in Melbourne from the Engwura, at speed. The first three of what became nineteen chapters were in Gillen’s hands by May 1897, only four months after the Engwura. You write like a dream! Gillen told him. Spencer kept firing off questions, puzzles, suggestions, Gillen chasing them down, loving it, the excitement of the hunt, the stimulus of Spencer’s “seething mind.” The chapters kept flowing up to Alice and back. It is going to be a great book! Gillen told Spencer. We look forward to the book of the century, one of the mutual mates wrote to Spencer. Gillen’s ambitions ran yet further ahead. I want to describe all of Australia’s tribes, he told Spencer, perhaps not realising that there were more than 500 of them, or had been anyway. You work like a steam hammer, he told Spencer as more chapters turned up in the post, you are working too hard, you must take a break. He didn’t. By March 1898, a bare fifteen months after the Engwura, less than four years after the two men met, a manuscript of 200,000 words, nineteen chapters, four technical appendixes, a glossary, index, an Authors’ Preface, 133 illustrations (mostly photographs) and two detailed maps was on its way to London.

But the course of this true love had not run entirely smooth. There had been spats, not many, but vivid ones, and about big things.

GILLEN’s understanding of both the Aboriginal apprehension of the world and their experience of oppression deepened rapidly as he worked toward the book. A few months after the Engwura he wrote to Spencer in anguish for his own and others’ actions in taking Aboriginal “churinga” (tywerrenge), inscribed boards and stones of deep spiritual significance. They had been collected in great number by the Horn expedition and then by one of Gillen’s mates and by Gillen himself until he realised how much they meant to their owners. He stopped collecting and asked his friend to stop too. He didn’t, with the result that the Aboriginal man who had revealed where the churinga could be found was put to death for sacrilege. “This upsets me terribly,” Gillen told Spencer. “I would not have had it happen for 100 pounds… I bitterly regret ever having countenanced such a thing and can only say that I did so when in ignorance of what they meant to the Natives… [I watched] them reverently handling their treasures – It impressed me far more than anything else I have witnessed.”

There was no cost to such sentiments, of course, coming as they did conveniently after the event. But scarcely a letter of Gillen’s fails to remark on the utter demoralisation of the Aborigines, their misery and the vicious incomprehension of the whites as to Aboriginal actions. He reports many incidents of shooting, of unjust punishment, of death from disease. He flares in anger at pastoralists who appropriate the best portion “for the exclusive use of their stock and relegate the Nigger to the barren wastes which are often destitute alike of game and tradition.” He is scathing about the Europeans’ ignorance of Aboriginal religious life. He even went, or tried to go, a step further than asserting its existence. He groped toward an understanding of its equivalence. The churinga (he wrote) are “sacred” in the sense that the sacramental wafer is sacred to the Roman Catholic. Aboriginal belief in the magical power of the churinga was like a Lourdes pilgrim’s belief in the Virgin Mary. He reckoned that the Dream Time (his neologism) wanderings were “startlingly like the wanderings of the Children of Israel.” Missionaries, Gillen said, were intent on wiping out the Aboriginal spiritual universe simply because it was rival to their own. Gillen was a proto-pluralist.

Sometimes he was even more than that. He was an anti-colonialist. “After I read your last letter I would have given a tenner to be alongside side [sic] you just to give you… a bit of my mind in return for your gratuitous attack on my Countrymen,” he stormed at Spencer. “With that arrogant assumption of superiority so characteristic of your Nigger annihilating race, you sneer at the Irish… You thank God that you are an Englishman, I thank God that I am not. I have no ambition to belong to such a race of Hypocrites. The British Lion shows his teeth but everyone, even you who are steeped in prejudice, know that those teeth are only decayed stumps and the poor old brute cannot bite. The stumps are good enough to crush niggers armed with weapons less dangerous than pea-shooters and that’s about all…” He often told Spencer that he (Spencer) was blinded by his imperial allegiance, that he wore “jingo goggles,” that “[your] environment has been too much for you – The hide bound toryism which encircles the walls of all british universities has got you in its grasp.” He foamed at the “oppressing, restraining, stifling, squelching, at times annihilating” of the Irish by the English, of England’s “old policy of crushing Irishism out of the Irish.”

This strand in the Gillen–Spencer relationship, occasionally prominent, rarely absent, has been passed over lightly by scholars, perhaps because so little of the contention between the two men is apparent in the upshot, Native Tribes of Central Australia.

Most of the book consists of loosely linked descriptions, and most of the descriptions are of ceremonies (of marriage, initiation, increase, and so on), but there were also scores of pages describing “magic,” social organisation, and “customs” (“knocking out of teeth; nose boring; growth of breasts; blood; blood-letting; blood-giving; blood-drinking; hair; childbirth; food restrictions; cannibalism” was the list of sub-heads to one chapter). Native Tribes is really a series of display cases filled with exotica. Material life, how the Aborigines actually earned a living, what governed their movements across their lands, how they brought up their children, what day-to-day life was like, all these were scarcely noted. Although Spencer and Gillen were the first to realise that “dreaming tracks” criss-crossed a landscape crowded with events and beings, and thus twigged to the rich omnipresence of Aboriginal spiritual life, they did not attempt to see it from the inside. They stared at what could be seen, from a distance. An appendix provides fifty-three measurements of the physiognomy of thirty numbered individuals. No individual is named or thanked, and differences in behaviour, personality and outlook are not recorded. Spencer and Gillen had returned from the site of a human catastrophe bearing a book about the fascinating things that had been there before.

Only rarely does the question of relations between black and white that so exercised Gillen find expression in their book. At five or six points appear sentences about the unwholesome influence of the whites (however kindly disposed they might be), the speed and inevitability of degeneration and extinction, and the declining numbers, all culminating in the following much-quoted passage. “[T]aking all things into account, the black fellow has not perhaps any particular reason to be grateful to the white man… To come in contact with the white man means that, as a general rule, his food supply is restricted, and that he is, in many cases, warned off from the water-holes which are the centres of his best hunting grounds, and to which he has been accustomed to resort during the performance of his sacred ceremonies; while the white man kills and hunts his kangaroos and emus he is debarred in turn from hunting and killing the white man’s cattle. Occasionally the native will indulge in a cattle hunt; but the result is usually disastrous to himself, and on the whole he succumbs quietly enough to his fate, realising the impossibility of attempting to defend what he certainly regards as his own property.”

The book’s reception almost matched Gillen’s fantasies. “In immortalizing the native tribes of Central Australia,” wrote Sir James Frazer, the eminent authority of the day, “Spencer and Gillen have at the same time immortalized themselves.” Native Tribes immediately became enshrined in the pantheon of anthropological classics. It influenced and was relied upon by such foundational works of the twentieth century as Durkheim’s Elementary Forms of Religious Life (1912) and Sigmund Freud’s Totem and Taboo (1913). It was a popular as well as academic success. Spencer in particular was in ever-increasing demand as a journalist and lecturer (on one occasion even filling the cavernous Melbourne Town Hall to capacity). Gillen was lionised in his home town and received at Government House. Spencer went Home on a victory lap and returned with his FRS. Their fame was such that funds were raised to send them on a year-long trip across the continent which resulted in two more books, Native Tribes of Northern Australia (1904) and Across Australia (1912). After Gillen’s death in 1912 Spencer wrote more books based on their work together, including one in their joint names, and became the nation’s foremost expert on Aboriginal affairs as well as the grand old man of the infant discipline of Australian anthropology.

One hundred and twenty years after the publication of their first book, Spencer and Gillen’s fame has not entirely faded. The telegraph station is a museum now. Some of the buildings in Spencer’s photographs have gone but most are still there and in good nick, too good really. The old telegraph office, with its high counter, pigeon-holes and telegraphic paraphernalia is particularly authentic-looking, but also pristine, like a lounge room when visitors are expected. Gillen’s den, that magic cave of spears and boomerangs and churinga, of clutter and whisky and pipe-smoke, is now just a room. There are photographs taken by Spencer and Gillen of the Aborigines and of Spencer and Gillen, their big droopy moustaches making them look like a stage duo or (as Gillen had fibbed) brothers. The texts describing them are oddly like Spencer and Gillen’s descriptions of the Arunta, as if seen through a pane of glass. Spencer is the subject of a magisterial biography by John Mulvaney and J.H. Calaby, and Mulvaney has collaborated with Howard Morphy and Alison Petch to publish two volumes of letters to Spencer, one volume of Gillen’s, the second of other Central Australian correspondents. These are works on which many, including myself, have depended.

But much of Spencer and Gillen’s faded fame has turned into obloquy. That process began before Spencer’s death in 1929. To the rising generation of academic anthropologists Spencer and Gillen seemed old hat and, increasingly, skeletons in the discipline’s cupboard. At the entrance to the splendid Aboriginal galleries of the Museum of Victoria, where Spencer was for many years honorary director, are two TV screens playing a loop of an imagined dialogue between Spencer and one of the impresarios of the Engwura cycle in which the wise old man chides Spencer for his unacceptable thinking. Despite the efforts of scholars, including Mulvaney and Morphy in particular, references to Spencer and Gillen in scholarly work and in more general commentary on “Aboriginal affairs” often depict them as archetypes of “scientific racism.” They would be better seen as bearers, shapers and captives of the Australian conscience.

WITH HIS constant agonising over the question of how to regard and behave toward the Aborigines, and his erratic swerves from one answer to another, Frank Gillen is almost a personification of the strange career of the Australian conscience. Like many others then and since his sense of right and wrong was formed by post-Reformation Christianity and Enlightenment humanism, but greatly intensified in his case by an Irish comprehension of colonial power.

Understanding that power, however, did not protect him from it. Gillen’s most courageous, even reckless, attempt to follow the dictates of conscience was in having William Willshire stand trial for murder. But it was Gillen, not Willshire, who lost that battle. The citizens of South Australia raised a substantial fund for Willshire’s bail and defence, successfully conducted by the colony’s leading QC, Sir John Downer. The Adelaide press pilloried Gillen, and applauded Willshire’s acquittal.

Gillen’s meeting with Spencer followed soon after this debacle, and in him Gillen encountered another form of cultural power. Spencer encouraged Gillen’s intellectual development and often boosted Gillen’s confidence and soothed his fears, but he also exercised, or simply embodied, an overwhelming national, institutional and intellectual power. It would be nice to imagine that Spencer, shaken by Gillen’s half-garbled but powerful insights, canvassed whether they should put the whole anthropological project aside and work up a volume to be titled The Destruction of the Native Tribes of Central Australia. Or perhaps even British Colonialism and the Destruction of the Native Tribes of Central Australia. But that didn’t happen, of course. My guess is that Spencer didn’t respond directly to these parts of Gillen’s letters except to mollify and sympathise. In effect Spencer – anthropology – said to Gillen: no, no, don’t look over there, look over here! Anthropology averted its gaze. It was an averted gaze. In fact, it was an averted gaze that said that it wasn’t. Trust Me!, anthropology said to Gillen, I am Science.

Whatever Spencer did or didn’t say to Gillen probably doesn’t matter. Gillen was excited by what anthropology was revealing as well as troubled by things it didn’t. His sense of right and wrong was at war not just with the world around but also with that within, with what he wanted. And Spencer brought what Gillen wanted so tantalisingly close that he simply could not resist. Gillen had no sooner vented his rage at Spencer’s “arrogant assumption of superiority” than he swerved away again, avoiding that one, last, fatal word. “Bah! I can’t keep my temper,” he wrote, “I shall grow abusive if I don’t stop. Ive [sic] had a smoke and feel better.” We might even talk about the hidden injuries of colonialism to explain Frank Gillen’s moral and psychological vulnerability, and equivocation. On the churinga, for example, he started out being opposed to collecting them then thought it must be okay because Stirling said so then changed his mind again as he learned “what they meant to the Natives” and eventually sold his collection.

There was weight of argument, too, or at least its force of attraction for Gillen: what could be seen in Central Australia and elsewhere in the spread of “civilisation” was not British colonialism or the greed of the cattlemen or the brutality of people like Willshire but the working out of a great logic, an irresistible process by which creatures quaint and crude give way to “higher forms.” What a calming doctrine this must have been for someone of Gillen’s temperament and outlook. Anthropology was a solution in the mind to a problem that could not be solved in the world.

But if Gillen makes a good Faust, Spencer does not make a very good Mephistopheles. For reasons of biography, temperament, training and domicile, Spencer’s conscience had nowhere near as much work to do as Gillen’s, but it was not entirely idle. He was a man of goodwill given specific form by the Dissenting Christianity of his upbringing and the progressivist humanism of his student days. He was influenced and educated by Gillen as well as Gillen by him. We might not like Spencer’s answers to the problems posed by conscience, but that does not mean that he was indifferent to them. Spencer’s diaries, much of his journalism, and above all his wonderful photographs, all suggest that his response to Aboriginal people was much broader and more complex than that seen in his anthropology. It might not be going too far to suggest that anthropology got the better of him as well as Gillen.

The defining quality of their work was not scientific racism but muddle, both of thought and feeling. At some points they belittled Aboriginal rituals and beliefs elsewhere documented with care and respect. Often they expressed admiration and affection for Aboriginal people and urged their readers to do the same, yet also talked about them as if they were a sub-species. The people Gillen routinely referred to as Niggers were also regarded by him as close friends. Spencer and Gillen asked their audiences to put themselves in the Blackfellas’ place but wrote almost exclusively from the whitefellas’ angle. They reminded their readers, however circumspectly, that the white man took the Aborigines’ food and water then exercised terrible violence if the Aborigines took the white man’s cattle, but they also talked about the destruction of Aboriginal societies as if it were a contagion, something as mysteriously fatal as it was inevitable. Gillen did his level best to have a cop sent down for murder yet remained (with Spencer) a vehement defender of the vigilante squads that hunted down dozens of Aborigines after the Barrow Creek killings.

Conscience was at work in everything Spencer and Gillen did, in their struggles with each other and with their own needs and desires as well as with the world around. The chronic and insistent problem was that their culture’s wants were incompatible with its beliefs (or what it wanted to believe its beliefs were, anyway). There are few villains and fewer heroes in the story of black and white in Australia; Spencer and Gillen were, like many others, neither, and both. If their conscience was never victorious, nor was it ever entirely vanquished, even in their anthropology. Their “science” did provide a powerful rationalisation for the conduct of white toward black and, more fundamentally, an angle of gaze that made it very difficult to see the things that so exercised Gillen. But anthropology was, and did, other things as well. It paid attention to the Aboriginal world when no other form of disciplined enquiry was interested. Its gaze was selective, but clear, certainly relative to its predecessors. William Horn, sponsor of the scientific expedition that brought Spencer and Gillen together in the first place, expressed a widely held view when he wrote that “the Aborigine” had no religion and no traditions, merely the mindless repetition “with scrupulous exactness” of “a number of hideous customs and ceremonies which have been handed from his father.” Spencer and Gillen, informed by their detailed scientific observations, knew that this was simply not accurate, and said so. Their anthropology allowed them to detect a spiritual world of unsuspected extent, complexity and feeling, a revelation that made possible the eventual transformation of racism into pluralism. Their anthropology’s empiricism was, in its way, a search for truth, the beginnings of an effort at comprehension that has continued ever since.

THAT SPENCER and Gillen’s anthropology was so influential and popular suggests that they shared with many others the need to find a new basis for moral comfort. They helped to give expression to a shift of a kind that a Kuhn or a Gramsci would quickly recognise, an abrupt movement from the dominance or hegemony of one paradigm of thought and feeling to another, provoked by a change in historical circumstances – in this case from a predominantly frontier to a post-frontier culture, a shift from a contempt and hatred unafraid to name itself to the averted gaze and crocodile tears of the great Australian silence.

Twenty or thirty years later Australia’s circumstances were again changing, this time through the emergence of a worldwide anti-colonialism, and the Australian conscience entered another phase in its strange career. Spencer and Gillen’s old anthropology became an important stalking horse for the new. The peerless W.E.H. Stanner, whose phrase “the Australian conscience” I have borrowed, was and saw himself as a conscience struggling (as he put it) to “escape” from Spencer and Gillen’s style of thinking. Even Stanner, along with many subsequent critics of our forebears, took for granted the conscience that brought him to criticise Spencer and Gillen, forgetting that his own conscience was as much a part of Australia’s history as the conduct it abhorred, and that the Australian conscience was as generative of Spencer and Gillen’s work as of his criticisms. Their work owed much to conscience, and Stanner owed much to it. It was Spencer and Gillen who gave him an attention to the Aboriginal experience when most preferred to ignore it, and the rigorously “scientific” form of enquiry essential to his “escape.” Stanner’s anthropology, which did so much to establish post-racist pluralism in Australia, was as much the offspring of Spencer and Gillen’s racist anthropology as its conqueror.

The beneficiaries of Stanner’s “escape” have also found it difficult to recognise the way conscience has worked, in the past, and in ourselves. One difficulty is empirical – the workings of conscience are often subterranean, and its results are often perverse – and that may be why historians and others have often failed to notice it. But the main problem is that we, like Spencer and Gillen (and Stanner), seek comfort.

The obvious advantage of concentrating on Spencer and Gillen’s vices is in highlighting our virtues. But to see only how we differ from them is to hide from the things we have in common with them. When on their transcontinental trek in 1901 Spencer and Gillen reached Alice Springs, they repaired once more to the rocky hill behind the telegraph station. “We found it difficult to realise [Gillen’s journal records] that it is 5 years since we last sat here together… puzzling over many things that were then strange to us but which have since been made clear and now lie enshrined in our book.” They believed that they had comprehended the Aboriginal universe and had seen its future. It is plain to us that that was a delusion of their age. But our age has delusions too. Perhaps one of them is represented by the playlet that greets visitors to the Museum of Victoria’s Melbourne Museum. In telling us that Spencer was a racist baddie it tells us that we are post-racist goodies, and implies that the conflict between conscience and interests culminated in the eventual victory of the former, with us. •

As noted above, the term “the Australian conscience” is Stanner’s. “Strange career” is from C. Vann Woodward’s 1955 classic The Strange Career of Jim Crow. Whether Spencer and Gillen’s hill-top sunsets began during Spencer’s first Alice Springs visit or the second (for the Engwura) I have been unable to establish.