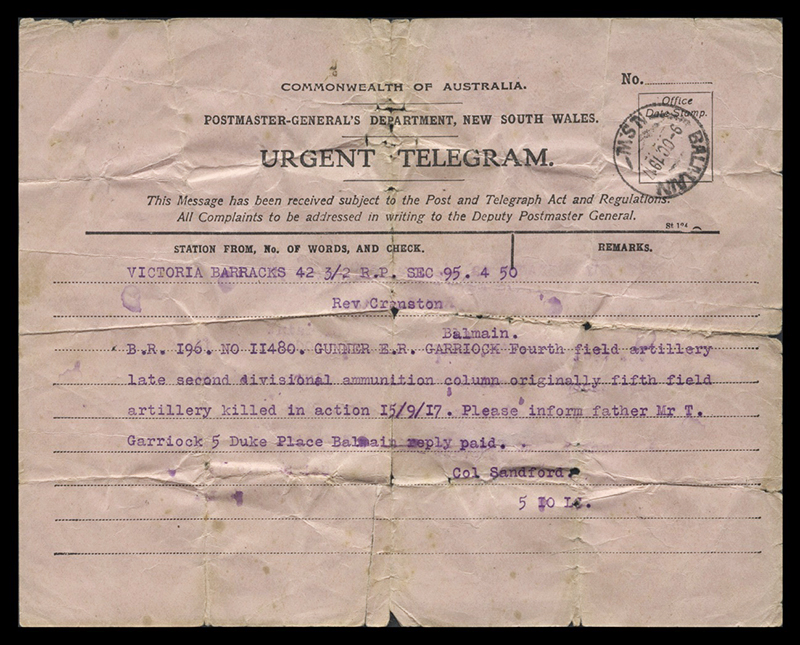

Gunner E.R. Garriock Fourth Field Artillery… killed in action 15/9/17. Please inform father Mr T. Garriock… Duke Place Balmain reply paid…

Duke Place is a tiny street in East Balmain, Sydney. Poor people don’t live there any more, but once this district was home to people working in the factories and dockyards around Mort Bay. Thomas Garriock was a labourer, and his son Eric was a plumber who had enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force in 1915.

The telegram had been sent on 9 October 1917 to the Reverend George Cranston, the minister at the Presbyterian church in Campbell Street, Balmain. It was his job to break the news of Eric’s death to the Garriock family. He probably delayed his call until the late afternoon when Thomas would be home from work and his wife Ann, Eric’s mother, would not be alone. So: a house, a doorstep, a nervous clergyman with a duty to perform.

As he stood there he might have smelled dinner cooking and heard the Garriock daughters chatting as they helped their mother. The oldest girl Ora had married in 1917, but Agnes, Annie and Robina were still at home. Their father was perhaps sitting in the corner with the evening paper. People often dreaded the sight of a clergyman in their street, and Reverend Cranston might already have been seen walking up Duke Place. Whose turn was it this time?

While life had carried on as usual at Duke Place, Eric had been dead for three weeks. He had given “Presby” as his religion when he enlisted, so it was up to Cranston to offer any comfort the family would accept. Breaking the news to nonbelievers, a clergyman could find himself back on the street in no time. But George Cranston and Thomas Garriock were fellow Scots, and perhaps this was enough to give Cranston entry to the household even if the Garriocks were not regular churchgoers.

It might also have helped that Cranston was a former army chaplain who had served sixteen months overseas in Egypt and France. Faced with the Garriocks’ pleading eyes he wouldn’t have needed to rely on empty platitudes: he would have ministered to many dying men, buried them, and written letters home to their families.

What most people wanted was the truth, however brutal. How did my son die? Where is he buried? Who was with him at the end? Cranston had no more information for the Garriocks that day than was in the telegram, but he would at least have been able to respond with something authentic from his own experience. Then, after leaving the telegram with the family, he would have walked back to the manse and to his wife, Marion. “Don’t hold dinner,” he’d probably said on the way out. “I don’t know how long I’ll be.”

What happened next? At this distance it is near impossible to know how grief played out in the lives of the Garriocks, and how long was the shadow it cast. This was not a well-off family with the leisure to preserve their feelings in letters and diaries. So, let’s come at it from another angle.

What happened to the telegram? Such a flimsy piece of paper for the weight of news it carried. Was it abandoned on the kitchen table? Did it flutter to the floor? Or did the family pore over it, searching for answers? Tens of thousands of similar messages were delivered all over the country between 1915 and 1918. What did people do with them? Is it something you would throw out, like a gas bill? How could you, with the words “killed in action” next to your son’s name?

In 1987, seventy years after this telegram was received, it was donated to the Australian War Memorial. If you order it up to the reading room today you are presented with a carefully preserved piece of paper in an acid-free cardboard folder. In researching this essay I found about ten official first world war telegrams like this at the AWM, and all came as part of small collections donated by families. Typically these collections might include some letters and cards home from the soldier, condolence letters after his death, commemorative memorabilia, information about his burial, a notebook or pocket diary, photographs and newspaper clippings. What families donate varies according to time and circumstances, and as a researcher in the reading room you never know quite what you will get.

A weight of news: the telegram that brought word of Eric Garriock’s death. Australian War Memorial

Still, I was taken aback when I opened the folder to find just this solitary piece of paper. I was tempted to shake the folder in case something else dropped out. But is this record any less weighted with meaning than those more elaborate collections? I took a second look. The telegram has been folded and looks as if it was carried around for a long time, resulting in tears along the creases and one of the folded surfaces becoming more rubbed than the others. Perhaps someone carried it in a wallet; Thomas probably, not Ann, because women carried purses in those days. Was that a strange thing to do? Who can say?

In pencil on the back of the telegram these words have been written in a small neat hand:

Dock Rs 1st 2 of storey house past Bay St

Directions to some waterfront location? Not the Garriocks’ own house, for there is no Bay Street in the area. Perhaps Thomas made the jotting himself when he needed to note something down and the telegram was all he had.

I wanted more context. I pulled up Eric’s war service record, which is held by the National Archives of Australia and viewable online. He died in one of the battles of 1917 known collectively as the Third Battle of Ypres. I was interested in any evidence of how his family dealt with news of his death and noticed that, unusually, no personal items were returned to them. A deceased soldier’s kit was always examined and anything not issued by the AIF was sent to his family, who were always anxious to receive anything, however trivial, as mementos. Soldiers couldn’t carry or store much stuff, but most had something: a wallet, a Bible, a few photographs, perhaps a pocket diary. But Eric’s service record notes that when he died he had no personal effects at all.

Still, as next of kin Thomas Garriock was issued with Eric’s service medals and the commemorative bronze plaque and scroll sent to all families of the British Empire war dead. Also standard was a photograph of the soldier’s grave, if there was one (some soldiers’ remains were never found). These photographs showed the temporary grave, usually marked by a simple wooden cross, preceding a soldier’s final interment, and were mounted in cardboard folders with the precise location of the grave given. Relatives could draw comfort from this information even though few could ever expect to visit the grave.

A photo was sent to Thomas by defence authorities in May 1920 and he replied to say how pleased he was, but he apologised that he could not afford to “improve” the grave. By that he probably meant that he would not be able to pay for an inscription when his son’s remains were permanently marked under a headstone. All headstones included the soldier’s name, military unit and date of death, but anything else had to be paid for by the family. The cost was thruppence ha’penny per letter for a maximum of sixty-six letters including spaces. Historian Colin Bale has estimated that the cost of a full inscription would be about a quarter of a basic adult weekly wage. At least a third of Australian identified graves have no personal inscription.

Thomas was so troubled about his inability to pay for an inscription that he wrote in 1922, unprompted, to apologise again. He had been invalided after an accident in 1917, he explained, and when his wife Ann died in 1921 the twelve-shilling weekly pension paid to her as a dependent of Eric’s was stopped. Thomas was living near Gloucester in northern New South Wales by then and relied on “the daughters” for everything he received. “I hope the country won’t forget the Boys who gave their lives for their King and Country,” he wrote. Maybe that was the inscription he’d have chosen: “For King and Country.”

Eric’s final resting place is in the Birr Cross Roads Cemetery, three kilometres east of Ypres, Belgium. Thomas Garriock died in 1946.

With archives, abundance is always regarded as a virtue. Breadth, depth, richness, variety: that’s what we want, and get, in the great deposits of personal records. The papers of John Monash, probably Australia’s most famous soldier, occupy sixty metres of shelving at the National Library of Australia and another six metres at the Australian War Memorial. Four major biographies have been written from them. In fact biographers’ careers can be built on access to rich deposits like these: subject, biographer and the holding institution can bask in a mutual glow of prestige and influence.

But fat biographies lull us into false expectations. What is actually held in archives and museums represents the merest fraction of the material evidence created in a society at any given time. Novelist Hilary Mantel expresses it best. History, she says, is “what’s left in the sieve when the centuries have run through it — a few stones, scraps of writing, scraps of cloth.”

How then do we grapple with scarcity, not abundance? We must begin with an awareness that many processes and circumstances are at play in the creation of records and their preservation as archives. Our man Eric Garriock probably did write at least a few letters or cards home to his family and it’s obvious from his enlistment papers that he could write — but these have not come to light, and nor has the photograph of his grave that we know existed. If he had a studio photograph taken in uniform before he left Australia, as many excited young enlistees did, it has not been donated to a public collection and nor have his service medals and the memorial plaque and scroll issued to his next of kin in the 1920s.

And the telegram? It has little obvious evidential value. By the time it was donated to the memorial in 1987, the memorial had long since collected the details of all the Australian first world war dead for its Roll of Honour in Canberra, so the telegram added nothing to the existing public record.

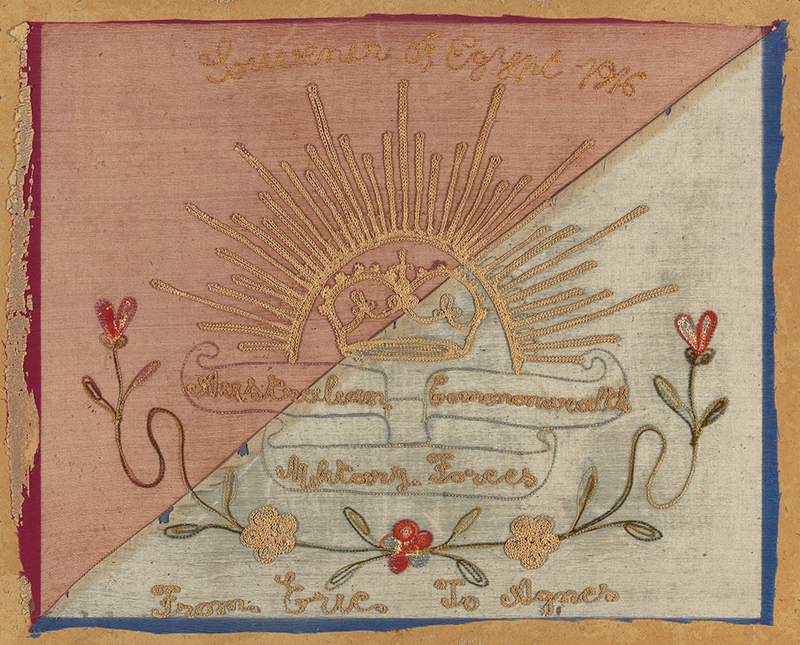

The file documenting the Garriock acquisition by the memorial is slender. It shows that the donor was a Mrs W. Bentley of Punchbowl, New South Wales. The only other item in the deposit is a piece of souvenir embroidery from Egypt with “From Eric to Agnes” inscribed in stitches. Such souvenirs were cheap to personalise and Eric obviously sent one home to his sister while he trained with his unit at a camp near Cairo in early 1916.

“Souvenir of Egypt 1916”: the embroidered greeting Eric sent to his sister Agnes in 1916. Australian War Memorial

The file contains no correspondence from Mrs Bentley to tell us about the Garriock family. Who was she? Electoral records show that Agnes Garriock, Eric’s sister, remained unmarried and lived in Punchbowl for many years, so Mrs Bentley may have been a younger friend who, on Agnes’s death in 1970, received some of her possessions. But while she cared enough to offer the telegram and the embroidery to the AWM, she may have known very little about them. No story — no anecdotes about Agnes or her long-dead brother — came with the donation when it was transferred to the memorial. Too many years had passed. There was nothing left to say. The emotion of that frightful moment in 1917 on the doorstep at the little house in Duke Place had all been spent.

The embroidery does yield a story of its own, though. It has been mounted on a stiff brown backing, and over many years light has faded the dyes in the base fabric, turning red into pink and blue to pale grey. You can see the original colours around the edges where the mount has crumbled and flaked away. This deterioration would have been arrested once the object was placed in museum storage. So? Agnes Garriock had it on the wall in her house for so many years it almost fell apart in front of her eyes.

They that are left grow old, and so does the material evidence of their loves and sorrows.

For Reverend Cranston, the Garriock telegram would have been one of dozens he had to deliver after his return from his own overseas service in March 1917. It was part of any parish priest or clergyman’s duties. Policy on this appears to have been formulated around the time the nation began to brace itself for the first casualties from the Dardanelles (Gallipoli). On 29 April 1915, defence minister George Pearce told the Senate that relatives of soldiers reported missing or killed would receive the news via a telegram delivered by a clergyman of the soldier’s denomination. (In the 1911 census less than 1 per cent of the Australian population had declared themselves non-Christian.) The names of the dead would then appear in the official casualty lists published in newspapers. Pearce’s announcement was reported in the press the next day.

In Britain and Germany, by contrast, messenger boys delivered the telegram, a terrible burden to place on the shoulders of boys aged not even eighteen. Many of them probably handed over the piece of paper and rode off on their bicycles as fast as they could.

The system in Australia was more humane, but there were still flaws. Sometimes the clergyman couldn’t break the news because the family was not living at the given address. In 1916 this was reportedly happening in about one in ten cases, which is why Base Records, the office set up in Melbourne by the defence department to handle soldiers’ records and coordinate casualty notifications, constantly pleaded with people to keep their addresses up to date. The ultimate horror was that families would read about a death in the newspaper, which did sometimes happen. Clergymen were required to notify authorities when they had delivered the message to each family so that the names could then go forward for publication, but there were a few who replied immediately only to discover that the telegram was undeliverable.

Behind all the procedures for keeping relatives informed was a continuous flow of information between Melbourne and locations overseas: Cairo and Alexandria in Egypt, Rouen in France, and of course London, where the AIF had its administrative headquarters. Nevertheless, information on the fate of a soldier could often be slow and vague, especially early in the war. Months often passed before the deaths of soldiers previously reported missing could be confirmed, and the Red Cross set up its own private enquiry service to assist relatives despairing at the lack of information from official channels.

In deciding to use clergymen to deliver the worst news to relatives, the government relied on the cooperation of churches, and for the most part got it. But people’s new dread of noticing a clergyman in their street impeded clergymen’s normal parish visiting. Before long, many began to regard the whole business as a terrible ordeal. Michael McKernan, one of the few Australian historians to have studied this aspect of home front history, corresponded with the son of a wartime clergyman who told him that his father had found the work “extremely distressing” and “never forgot how it hurt.”

The personal service records for all members of the AIF are held by the National Archives of Australia. On them are copies of telegrams to families notifying them that their soldier had been reported wounded or sick, but rarely do we find telegrams for the missing or dead. For years I wondered how the system had worked. Clergymen broke the news, yes, but how did they know who had died, and where to call?

In 2019 I found the procedure described in an obscure defence department report published in 1917. A telegram was sent by Base Records in Melbourne to the military district in which the soldier had enlisted (the 2nd, in Eric’s case, which was New South Wales), and the commandant then authorised a telegram to the relevant clergyman. Back at Base Records, a small note was made on the soldier’s file that the necessary action had been taken. So, on Eric’s file we read: “Oct 8 1917 MC2 advised killed in action 15/9/17.” But you must be very sharp-eyed to notice it.

All of the military districts were state-based and they must have liaised with all archdioceses (and equivalents) to keep a record of the names and locations of priests and clergymen in all Christian denominations in their state, backed up by a substantial recordkeeping sub-structure of ledgers, indexes and correspondence. I have found no trace of any of it, at least not at the National Archives. Relevant records might still exist in church archives, or evidence in clergymen’s private papers or in local histories, but they would be scattered across the country. But even fragmentary records might expand our knowledge of how priests and clergymen became home front foot soldiers for the state during the first world war.

The urge to make a story out of these slivers and fragments is irresistible. I keep probing the Garriock story from different angles, searching, as novelists and biographers do, for hints and different perspectives to fill gaps and absences. I want to give Eric Garriock’s life some meaning apart from the fact of his early death. When it was founded in the 1920s and 1930s the Australian War Memorial was a national repudiation of meaninglessness: what parent can accept that their child has died without a reason? That is why it built its collections with such relentless determination in those early years, and why the quiet simplicity of the building in Canberra was so important. There had to be solace somewhere, surely?

But no mountain of paper or pile of stones will bring back the dead. The Garriock telegram confronts us with the terrible mystery of death. He breathed, and then he didn’t. He is not coming home. •