The wave of protests that swept through Indonesian cities and towns last week bore more than a few resemblances to those that brought down the Suharto regime in 1998.

Some of the similarities are obvious. On both occasions, violence by security forces caused protests to escalate. In 1998, the shooting of students at Jakarta’s Trisakti University triggered mass rioting, generating the final crisis that forced Suharto to step down. Last week, the killing of a motorcycle taxi driver, Affan Kurniawan, sparked an uptick of rage across the country. Protesters began to attack and burn government buildings (at least eight regional parliament buildings were burned down, by my count) and to launch mass raids on the homes of prominent politicians, such as People’s Representative Council (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat, or DPR) member Ahmad Sahroni and finance minister Sri Mulyani.

In 1998, as today, the backdrop of the protests was partly economic. In 1998, the Asian financial crisis caused Indonesia’s economy to collapse, driving millions into poverty and forcing many companies into bankruptcy. Economic conditions are not so severe today, but the economy is slowing, and the middle class is shrinking. Central government efficiency measures have badly affected numerous sectors: many regional governments, for instance, have raised land and property taxes in response. Labour informality and precarity are rising, both with the growth of the gig economy and with layoffs in manufacturing. And all this comes amid severe economic inequality.

This setting helps to explain key features of the recent protests, such as participation by members of labour unions and rideshare drivers, even the targeting of the home of Sri Mulyani — so long the darling of middle-class liberals and reformers, now the public face of austerity to many protesters.

Perhaps the greatest similarity between 1998 and 2025, however, is that both protest waves built on a subculture of street protest that had been growing for several years. The trigger in 1998 may have been the Asian financial crisis, but protesters that year were able to draw on the experiences — and the antipathy to governmental authority — many of them had built up through several years of escalating social and political unrest. An ethos of protest and opposition to the Suharto regime had spread on campuses, in sections of the middle class, and among many members of the urban poor, laying the groundwork for 1998.

Today, the dynamics are similar. The protests of 2025 definitely didn’t come out of nowhere. Instead, they are at least the fifth major wave of youth-led mass protest since 2019. First came protests in September and October 2019 triggered, above all, by DPR and government moves to strip the hitherto very effective Corruption Eradication Commission (Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi) of key powers.

A year later, in 2020, another wave of protests greeted the passage of the so-called Omnibus Law on Job Creation, which among things accelerated the shift toward casualisation of the labour force and weakened environmental protection for natural resource investments. The “emergency warning” (peringatan darurat) protests of August 2024 the February 2025 “dark Indonesia” (Indonesia gelap) protests had distinct triggers and immediate targets, but all of these waves expressed a similar critique of Indonesia’s political elite and the corruption that pervades it. The economic and class dimension is stronger in the current protest wave, but that too builds on features already present in earlier episodes.

Each of these five waves of protest has represented another marker in Indonesia’s democratic decline and authoritarian revival. But they are also significant in their own right, pointing toward the emergence of a new protest counterculture in Indonesia’s towns and cities.

Building on earlier traditions of social protest, this new counterculture is centred on a deep and growing antipathy to Indonesia’s governing elite. United by new modes of online communication, ever-changing networks of loose organisations, as well as connections among more established institutions, such as student executive councils, labour unions and NGOs, this movement is ideologically diverse — but it’s united around common threads of opposition to oligarchy, anger at the corruption of the ruling elite, and rejection of growing economic inequality.

Indonesian scholars and activists have noted the “rhizomic” quality of the new youth protest and social movements, and their diffuse and leaderless patterns of organisations. While some celebrate these qualities, pointing out the participatory character of the new youth movements and how their flexibility makes them difficult to eradicate, others have argued they lack the organisational strength and ideological clarity needed to bring about fundamental social and political change.

The recent protests can thus be understood as product of a clash between two worlds of Indonesian politics: the world of official representative politics and the subculture of youth protest that rejects it. Part of what explains the severity of the protests is that, while the protesters understand the world of the politicians quite well, the reverse seems not to be true — at least until now.

When it was announced that DPR members would gain generous new allowances — a key precipitating event in the current round of protests — on top of their already large salaries, these politicians obviously saw themselves as gaining a well-earned reward. Elected politicians routinely complain about the onerous expectations of cash and other forms of assistance they face from constituents, and many of them undoubtedly believed their de facto wage increase would help them address this problem.

But the announcement and the verbal somersaults of those justifying it — to say nothing of footage of DPR members dancing happily during a recent parliamentary session — came while many Indonesians were experiencing deepening economic hardship, betraying a remarkable lack of understanding of how such news might be received by members of the public.

Throwing fuel on the fire, some DPR members went on social media to mock and disparage the protesters. Ahmad Sahroni, a particularly wealthy and brash politician, called protesters seeking the dissolution of the DPR the “stupidest people on earth,” prompting media outlets to remind readers of his fantastic wealth. Sahroni soon got his comeuppance when protesters attacked and looted one of his homes, parading luxury items they found there — such as a life-sized Ironman sculpture — on social media.

How could the gap between these worlds become so wide that Sahroni and other DPR members could make such fateful miscalculations? In the early years of the post-1998 Reformasi period, elected politicians were at least somewhat attuned to the world of street protest. They had seen how it could bring down a regime, and they were careful to pay attention to what protesters wanted and, where possible, to concede — even if only partly or symbolically — to their demands.

Time passed, and most of that first generation of post-Reformasi politicians passed from the scene, to be replaced by a new breed of politicians (often the children of the first generation) who were inculcated in, and products of, the culture of money politics that has grown within Indonesia’s democratic institutions. As vote-buying and other forms of patronage politics became increasingly entrenched as the main way to win elections, DPR members and other politicians had to invest increasingly vast sums of money in their campaigns. More and more of them come from wealthy business backgrounds, or from established political dynasties.

These shifts have changed the political culture and patterns of work within Indonesia’s representative institutions too, increasing representatives’ need to use their official positions to generate income, or at least to access streams of patronage. A decade or so ago, as a researcher one had to tread carefully when investigating topics such as vote buying or informal fundraising within the DPR. As time has passed, my impression is that DPR members and other politicians have become increasingly open about discussing such topics, as these practices have become normalised.

Insiders, too, give accounts of how new members of institutions like the DPR are inducted into a culture of corruption by their seniors. A few months ago, one relatively young member of the DPR explained to me and colleagues what it’s like to be a member of that institution:

[I]f you talk about defending the rights of the people, they will laugh at you, they will come to you and say “don’t be too serious”… “don’t be so holy.”… But if you talk about money, well, they will all come and deal with you very seriously and carefully. If you want to explain which projects will give you 30 per cent, they will brag about it.

Ordinary Indonesians notice these changes too. Corruption investigations — especially those launched in the past by the KPK — exposed the fabulous wealth of many politicians, with raids on their homes exposing collections of Hermès bags, Lamborghinis and similar luxuries. Politicians themselves have become increasingly open about flaunting their wealth on social media. At the same time, we know that politicians’ policy preferences track with those of high-income voters, rather than with ordinary citizens, in areas such as social welfare and redistribution.

In short, years of patronage politics have created an ever-widening gap between the political world of the governing elite who inhabit Indonesia’s democratic institutions, and that of the young protesters whose forebears played such an important role in putting those institutions in place.

Despite the many similarities, differences between the protests of 1998 and 2025 also stand out. For one thing, much of the violence on the part of rioters, and the looting, has been much more targeted so far than in 1998. In 1998, especially during Jakarta’s May riots, people attacked symbols of wealth and property in general, and there was much racist targeting of ethnic Chinese persons and property in particular. This time, as well as violence generally being at much lower scale, there have not been (so far as I am aware) verified reports of anti-Chinese violence — despite many rumours and fears that it was imminent. Instead, violence has been directed against figures and symbols of state authority: the police, official buildings, the private homes of politicians, and the like.

The political objectives of the current protesters, by contrast, are much more diffuse than those of their forebears in 1998. What gave the Reformasi movement much of its power was the precise nature of its goals, embodied in a number of daunting, but ultimately achievable, goals: the overthrow of Suharto, the end of the military’s “dual function” (dwifungsi), the dismantling of restrictions on political expression, and so on. Those goals could be achieved in part because the protesters were able to find allies, not only among members of mainstream political parties, religious organisations and the like, but also within the ruling civilian and military elite, many of whose members ultimately abandoned Suharto and threw in their lot with Reformasi.

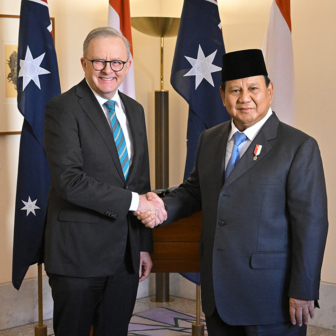

Today the protesters’ goals are not limited to forcing out any particular leader or party, or even to repeal a limited set of laws or regulations. To be sure, they have many such targets — many of the protesters call on president Prabowo Subianto to step down, for the DPR to be dissolved, and for various laws and regulations to be repealed. But what they really stand for, above all, is rejection of the entire ruling elite.

And the entire ruling elite, more or less, stands united against them. This was symbolised dramatically on 31 August when leaders of all the major political parties lined up next to Prabowo as he delivered a speech in which he mixed concessions (cancelling the DPR members’ new allowances) with threats (accusing protesters of engaging in treason — makar — and terrorism).

As a result, it’s hard to see any way by which the current confrontation between the two worlds of Indonesian politics will disappear soon. To be sure, the current wave of protest may well disperse soon, as did the previous ones — in fact, it seems to be on this pathway as I write this piece. But so far, each wave has been followed by another, on virtually an annual basis. That pattern seems likely to continue. Elite politicians are trapped in a system of patronage politics that they would find hard to escape even if they wanted to. As a result, the protesters are a long way from achieving their goals, and their antipathy to Indonesia’s political class is unlikely to dissipate.

This, too, makes the current period seem different from the late Suharto era: back in the 1990s, even when protests were suppressed by the military, the most militant groups always believed they were working toward a defined goal: the overthrow of the Suharto regime. Today’s targets are not so well defined, and are captured by terms — oligarchy, corruption, and the like — which point toward deeply entrenched informal relations of power. Ending such phenomena will require deep systemic change, rather than a limited number of formal legal adjustments or reforms.

It’s hard to envisage such change occurring with the current crop of elite politicians holding elective office. Yet replacing them is not easy either. When progressive activists have ventured into the electoral arena in Indonesia they have almost invariably failed (in sharp contrast, for example, with Thailand). The elite politicians the protesters so revile enjoy massive organisational and material advantages that make them very difficult to beat, especially when so many voters have come to expect patronage in exchange for their votes. These politicians also operate political machines that reach right down into the communities where ordinary Indonesians live throughout urban and rural Indonesia — something the protesters also lack.

Overthrowing Suharto was a titanic achievement. The goals of the current round of protesters are arguably no less daunting. •

This article first appeared in New Mandala, an online magazine hosted by the Australian National University’s Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs.