W. Macmahon Ball: Politics for the People

By Ai Kobayashi | Australian Scholarly Publishing | $39.95

The Bracegirdle Incident: How an Australian Communist Ignited Ceylon’s Independence Struggle

By Alan Fewster | Arcadia | $39.95

Undesirable: Captain Zuzenko and the Workers of Australia and the World

By Kevin Windle | Australian Scholarly Publishing | $39.95

THERE is a powerful myth about Australian history that contrasts the conformist and inward-looking Australia of the 1950s with the supposedly cosmopolitan, competitive and outward-looking nation we now live in. Although this seems to me a simplistic account of what has happened to Australian society over the last half century or so, it is true to say that the rest of the world — and especially Asia — seems rather closer to us than it once did. Just a few days ago, my own university, the Australian National University, sent around an email explaining that for some reason, staff using the internet had been locked out of key Chinese websites. The matter was reported as something that would be of serious concern to staff, much as the residents of a suburb might be inconvenienced by an electricity blackout or if the gas were cut off.

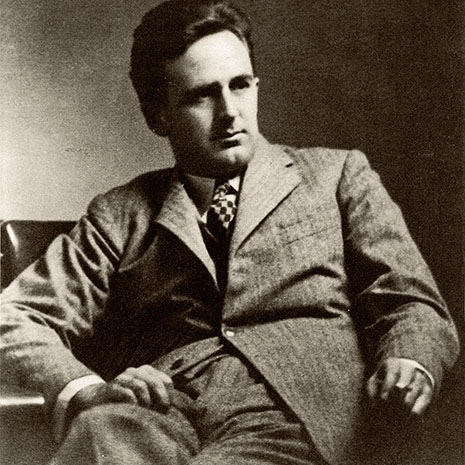

All of this seems a far cry from the Australia of William Macmahon Ball, the pioneering Australian political scientist and foundation chair in the discipline at the University of Melbourne, who is the subject of an admirable biography by Ai Kobayashi. As the director of broadcasting activities in Australia’s Department of Information during the second world war, Ball received an instruction that his shortwave division “should begin broadcasts to Thailand,” then under Japanese occupation. There was just one problem; he couldn’t find anyone in Australia with sufficient knowledge of Thai history, geography, language and culture to help him. So he sought out a former student who needed a job, and gave him ten days “to become the Australian expert on Thailand…and he did.”

Australia now has its fair share of Thai experts, and for that and much else we owe Ball a considerable debt. He became Australia’s foremost advocate of what we now call Asia-literacy, a commitment forged partly through his own role as a diplomat in Asia in the 1940s — notably as the British Commonwealth representative on the Allied Council for Japan. It was not a role in which he flourished, for he was frustrated by the Americans’ unwillingness to cooperate as the cold war descended, as well as by the erratic — and, as Ball eventually saw it, disloyal — behaviour of Australia’s external affairs minister, Herbert Vere Evatt. Nonetheless, Ball’s postwar experiences in occupied Japan, as well as his work in wartime broadcasting and some other 1940s diplomatic encounters with Asia, helped instil in him a lifelong belief in the importance of Australians’ having a better understanding their own neighbourhood.

Ball wrote books about Australia and Asia but he was not what we would consider an academic specialist in the field. He did not have an Asian language, nor did he show any interest in acquiring one. But he promoted Melbourne University’s politics department, of which he was effectively the founder, as a centre for the study of Asia. And he used his gifts as a communicator and advocate to increase public awareness of Asia, and to promote a better understanding of the region.

Ball had won a reputation in the 1930s as a broadcaster and newspaper commentator on world affairs. Kobayashi presents him as a generalist in an age of increasing specialisation, a public educator at a time when there was growing (if not yet compelling) pressure on academics to write more and more about less and less, and to publish their work not in widely circulated newspapers and magazines but in academic journals. They were increasingly expected to spend their time in the seminar room rather than on the public platform or in the studio. According to Kobayashi, “as an educator and publicist for political studies,” Ball “demonstrated the role of an intelligent man rather than a scholar in the field.”

By the time he retired in the late 1960s — having built up a major department at Melbourne — Ball seemed a bit of an academic anachronism, but new spaces had begun opening up in the media for academics in the humanities and social sciences to play their part as public intellectuals once again. Today, we can surely see a continuation of the Ball tradition in the work of international relations scholars such as Hugh White and Michael Wesley — academics who move with apparent confidence across a range of specialties as well as between universities, the public service, think tanks (Ball himself almost accepted an invitation to New York to work for the Institute of Pacific Relations) and the media. They write and speak for an intelligent general audience and for policy-makers, rather than primarily for academic specialists. Perhaps more than those students of Ball, such as Jamie Mackie, who became the Asian area specialists of the next generation, it is figures like these who are his spiritual heirs and successors.

AT THE very time that Ball was beginning to think seriously about Australia’s relationship with Asia, one of his compatriots was making a more direct mark on the politics of the region. The name of Mark Bracegirdle is no better known in Australia today than that of William Macmahon Ball. Alan Fewster’s intriguing The Bracegirdle Incident might only make the man a little more familiar, although it is hard to disagree with Humphrey McQueen, in his foreword, that the story is ripe for television dramatisation.

Born in London in 1912 to a mother who was an artist, suffragette and Labour political activist, and a father who worked in business, for a couple of years in the 1930s Mark Bracegirdle became Australia’s face in Ceylonese politics. I recall seeing Mark’s younger half-brother Simon at a conference on Marxism in Brisbane in the mid 1990s. Simon, we learn from Fewster, had been conceived from an affair between the boys’ mother, Ina, and one Colonel Agar. Ina and her husband separated, perhaps as a result of this adultery, and the mother with her two boys migrated to Australia in the mid 1920s. Simon was later active in the New Theatre and the Communist Party. Mark, too, joined the Communist Party of Australia, but in 1936 he went to Ceylon to work as a “creeper,” an apprentice tea planter.

He didn’t last long in this occupation. Having been sacked for fraternising with his workers, Bracegirdle made a notorious speech on 4 April 1937 in front of a crowd of 2000 locals. Speaking through an interpreter, he is supposed to have said, “Do you see those hills? Do you see those bungalows? There the whites live in luxury! They suck your blood!… They are parasites… Come on, I will help you; I will lay down my life for you. Rise! Rise and win your freedom and gain your rights!” Bracegirdle was never called on to lay down his life, but the colonial government did serve him with an order for his deportation. In the eyes of the authorities and the planting community, Bracegirdle committed the most unpardonable of sins; he had “gone native” and used his prestige as a white man against his own people.

For local nationalists and radicals such as those in the Trotskyist Lanka Sama Samajist Party, Bracegirdle was a godsend, and they sought to milk the controversy for all it was worth. They helped their new friend go into hiding, and at one stage he spent a week alone in a cave with just “a few tins of food, some tea and a billy can” while he cut notches on a stick to note the passing of each day. The Australian was eventually arrested, but he would not be long in custody because his lawyers successfully petitioned the Supreme Court for a writ of habeas corpus. Later in 1937 he left Colombo for London, where he would eventually settle. But the Bracegirdle affair dragged on, having become a major controversy in local politics and a notably contentious issue between British colonial administrators and leading local politicians. The matter made it all the way to the British cabinet.

As fascinating as the episode is, Fewster’s account of the manner in which it became entangled in Ceylonese politics might contain a little more detail than readers will feel they need. And I would have liked to know more about Bracegirdle’s life after leaving Sri Lanka (he died in London in 1999), but Fewster has seemingly been unable to turn up much information. Bracegirdle apparently spent time in Berlin just before the war “and became a smuggler of refugees.” He was also a lifelong left-wing activist, participating in the Aldermaston marches against nuclear weapons. His Guardian obituary intriguingly remarks that “Bracegirdle knew about fungi, the history of Chinese script, Darwinism, the history of science, Marxism, Roman glass, ornithology, farming, art, design, aviation, beekeeping, Aboriginal history — and cookery.”

ALAN Fewster doesn’t discount the possibility that Mark Bracegirdle was an agent of the Third Communist International (Comintern). One man who we can be more certain worked as a Comintern agent was Alexander Zuzenko. On 25 August 1938, Zuzenko was shot in the head by an executioner from the NKVD, the Soviet secret police under Stalin. This brought to an end a most unusual life, which had taken the man across the world, including to Queensland, where he was a member of the pre–first world war Russian community. Kevin Windle’s Undesirable: Captain Zuzenko and the Workers of Australia and the World is a most engaging tale of a man fired by the ideals of 1917 who, like millions of his comrades, would eventually fall victim to its grotesque turn under Stalin’s dictatorship.

Hailing from Riga in Latvia and already a confirmed revolutionary by the time he arrived in Australia (probably late in 1911), Zuzenko was active in the Brisbane Russian community. As a result of the work of a number of scholars, including Windle — and of the assiduous efforts of our own nascent intelligence service, which did its best to document their supposedly subversive activities — we now know a good deal about the Russians of Queensland in the early years of the twentieth century. They are probably best recalled as the victims of the returned soldier violence in 1919, when their hall was attacked by a riotous mob. Zuzenko, seen as a ringleader among the Russian socialists, was arrested and deported. He and his Russian wife and family would eventually find themselves in the new workers’ republic, but not before some dangerous moments during the civil war, since Zuzenko had landed in Odessa when it was still controlled by anti-Bolshevik forces.

Windle does a superb job of tracing Zuzenko’s subsequent — and rather chequered — career as a minor Bolshevik apparatchik, Comintern agent and sea captain through a wide range of very scattered sources. He appears as a thinly veiled character in a number of fictional works by Russian authors, not least because he managed to find himself moving among some illustrious cultural identities: he knew both Mikhail Bulgakov and Alexei Tolstoy.

Despite the fact that he had formally renounced his early allegiance to anarchism to become a Bolshevik, there is good reason to think he never quite left behind his earlier faith — and the powerful streak of independence that went with it. Nonetheless, almost until the very end of his life, Zuzenko seems to have been an unswerving defender of an increasingly brutal regime, perfectly content to engage in violent public abuse of its traducers. Having managed to persuade the Party that he was just the man to spread the revolutionary message among the Australian comrades, he was appointed Comintern agent to Australia. But he found himself stuck first in Britain and then in the United States, unable to get the paperwork needed to continue his journey. What should have taken six months took well over two years.

After slipping back into Australia, Zuzenko found some rather quarrelsome comrades. There were rival Communist Parties in Sydney, each claiming to be the bearer of Moscow’s imprimatur, and he exercised some influence in ensuring that the group centred on Trades Hall in Sussex Street prevailed as the officially recognised party. He was not long in Australia, for the authorities soon arrested him. But their apparent efficiency did not prevent Zuzenko from reporting to his political masters, when he arrived back in Moscow, that he was “firmly convinced that the first of all the Anglo-Saxon countries to declare itself a true Workers’ Republic will be AUSTRALIA.” This was, of course, in large part an assertion of his own significance as the Bolsheviks’ Australian man.

“Our children, if they don’t grow up to be complete idiots, will envy us,” Zuzenko reflected upon witnessing Lenin lying in state after his death in January 1924. “We’ve penetrated into the very heart of history.” He might have been tragically deluded, but all three of these books, in their different ways, do place Australian history at the heart of modern world history. In Macmahon Ball, witness an Australian who sought to understand what the rapid, massive changes in the world order would mean for a British country being dragged, much against its will, into having to fend for itself in international affairs. The Bracegirdle incident places an Australian Communist briefly at the epicentre of the anti-colonial struggle in South Asia. And Windle’s story of Alexander Zuzenko reminds us that Australia, too, was swept up in the optimism and the tragedy of the era Eric Hobsbawm so aptly called “The Age of Extremes.”

All the same, it is useful to be reminded that on 7 November 1917, the day the Bolsheviks stormed the Winter Palace in Petrograd, Zuzenko appeared in a court in Ingham and was fined 10 shillings plus costs under the War Precautions Act. He had lost his registration certificate “through a hole in his pocket.” •

This article has been updated to correct the date of Mark Bracegirdle’s birth.