Australia was born urban and quickly became suburban. Almost as quickly, the idea of the suburb – the location of the Great Australian Dream – began to attract its enemies, here and across the Western world. At first, though, the enemies of the suburb were far outnumbered by its friends. But over the past century and a half public opinion has gradually shifted in their favour. How and why did this revolution in attitudes occur? And how much do modern critics of the suburb owe to their Victorian and Edwardian predecessors?

In their reasoning, friends and enemies of the suburb agreed almost as much as they disagreed. Both accepted the physical determinism that underlay the “logic of avoidance,” the esentially negative character of the suburban impulse. Suburbanites, they assumed, would, in fact, be healthier, more virtuous (according to middle-class standards), more family-minded and closer to nature. They disagreed, not because they thought that the suburbs made no difference to the lives of the suburbanites, but because they thought they made the wrong sort of difference. What suburbanites regarded as virtues, the suburbs’ enemies saw as vices. The suburbs were simply too spacious, too clean, too safe, too conventionally virtuous, too sanctimonious.

Libertarians rebelled against the evangelical morality that prized domestic privacy. Socialists opposed the suburbs’ effect on class segregation. Aesthetes, influenced by European realism or decadence, questioned the romantic idealisation of nature. Even the fears of bad air and overcrowding slowly dissolved as doctors embraced more complex theories of bacterial transmission. A way of life that was once prized gradually came to be seen first as contemptible, then as dangerous, and finally as downright irresponsible.

But before it became contemptible, the suburb was seen as simply ridiculous. William Thackeray, the satirist of London snobbery, sent up the saints of suburban Clapham in his comic novel The Newcomes (1855). In Our Mutual Friend (1865), Charles Dickens mocked “Mr and Mrs Veneering” as “bran-new people in a bran-new house in a bran-new quarter of London.” A decade later, Marcus Clarke took a swipe at Melbourne’s new rich in a sketch of Mr and Mrs Wapshot, residents of “Nasturtium Villas,” a seaside suburb. The faults of these suburbanites were those of the new rich everywhere: they had too much money, too little taste and no sense of humour.

Only towards the end of the nineteenth century did the suburbanite emerge as an explicit topic of social commentary. Mr Pooter of “The Laurels,” Brickfield Terrace, Holloway, the comic hero of George and Weedon Grossmith’s The Diary of a Nobody (1888), is a lower middle-class cousin of the Veneerings and Wapshots. What endears him to us is his simple-hearted domesticity, his cheerful embrace of the suburban idea. “After my work in the City I like to be at home… ‘Home, Sweet Home,’ that’s my motto,” his diary begins. Content with a mundane round of horticulture, home improvements and his circle of like-minded friends, he is the prototype of a figure who appears, sometimes in more tragic guise, in the writings of Edwardian novelists, like H.G. Wells.

The most famous satirist of the Australian suburb, Barry Humphries, is a descendant of the Grossmiths. During the 1950s Humphries read The Diary of a Nobody and decided to write a sketch about a “decent, humdrum old man of the suburbs.” As his model, he took Mr Whittle, an inoffensive old man he often passed on his way to the station from his parents’ home in suburban Melbourne. “Mr Whittle,” Humphries recalls, “came to represent not merely my parents’ generation, but Respectability itself. He represented punctuality, industry, courtesy, thrift, temperance, niceness. I despised him.” He became the model for the most affecting of Humphries’s gallery of Australian suburban types, Sandy Stone. While his most famous character, Edna Everage, evolved from mousy housewife to spangled superstar, and from satire to burlesque, Sandy remained what he always was – a face for the deep pathos that Humphries detected beneath the complacent surface of suburban life.

Security, sedentary occupation and respectability were the hallmarks of “the suburbans,” as C.F.G. Masterman called them in his perceptive book, The Condition of England (1909). “It is no despicable life which has thus silently developed in suburban London,” he wrote. “Family affection is there, cheerfulness, an almost unlimited patience.” But there was something about its self-limiting, self-centred and spiritually enervated atmosphere that left him dissatisfied. Like Wells, Masterman pondered the possibility that the suburbs – still a small segment of London society – might eventually become everyone’s way of life. “Is this to be the type of all civilisations, when the whole Western world is to become comfortable and tranquil and progress finds its grave in a universal suburb?”

For all its prophetic insight, there is more than a whiff of condescension in the Edwardian critique of the suburbs. Masterman and Wells were refugees from suburban London and, in deriding its limitations, they were proclaiming their own emancipation. Condescension could easily harden into alienation. In 1910 the Australian socialist playwright Louis Esson declared:

The suburban home must be destroyed. It stands for all that is dull, and cowardly and depressing in modern life. It endeavours to eliminate the element of danger in human affairs. But without danger there can be no joy, no ecstasy, no spiritual adventures. The suburban home is a blasphemy. It denies life. Young men it would save from wine, and young women from love. But love and wine are eternal verities. They are moral. The suburban home is deplorably immoral.

A self-conscious Bohemian whose marriage was on the rocks, Esson saw the suburban home as a symbol of the Puritan values that, by now, had taken a strong hold on the public life of Melbourne. In rejecting suburbia, he inverted the value system of its creators but endorsed the equation between morality and urban form that underlay it.

In the early twentieth century, the attack on the suburb gradually broadened to include its economic, environmental, hygienic and social features. The evils of suburbia, these new critics suggested, were manifest in an insidious disease they called “sprawl.”

Few words in the history of urban planning have been so potent. “Sprawl” – literally “an awkward or clumsy spreading of the limbs” – originally denoted the unsightly, unplanned ribbon development on the edge of cities and towns, but it gradually became a synonym for almost any low-density or peripheral development at all. Its adoption as a self-conscious planning slogan appears to date from 1883, when the socialist and aesthete William Morris addressed an audience in Oxford on “Art under Plutocracy.” Art, Morris insisted, was something that should shape the material lives of the many, including their homes and towns, as well as the palaces of the few. “Need I speak to you of the wretched suburbs that sprawl around our fairest and most ancient cities?” he asked, by way of example. He was thinking of the (to him) ugly redbrick villas being erected on the circumference of Oxford.

Among Morris’s disciples (he may even have been present at the Oxford lecture) was his fellow socialist Raymond Unwin. By 1909, when Unwin published his influential book Town Planning in Practice (1909) and the House of Commons debated the first British Town Planning Bill, the disease – what Unwin called “that irregular fringe of half-developed suburb and half-spoiled country which forms such a hideous and depressing girdle around modern growing towns” – was well recognised, even if the word had not yet become standardised.

The noun “sprawl,” along with a standard lexicon of adjectives (“depressing,” “haphazard,” “dreary,” “ugly,” “shapeless,” “straggling,” “prosaic,” “unlovely,” “mushroom”), soon entered the vocabulary of Australian planners and architects. When the architect Kingsley Henderson observed in 1921 that “the suburbs had simply ‘sprawled’ outwards,” the quotation marks signalled the word’s arrival as a self-conscious planning slogan.

“Sprawl” was an anthropomorphic concept – it conjured up the image of a lazy, untidy, inconsiderate invader of other people’s space; a couch potato monopolising the national living room. Making the concept human invested it with human faults requiring censure and discipline. The usage gained currency at about the same time as the word “suburbia,” which was also often invested with humanoid qualities. “Suburbia lifts itself on the hills or snuggles in the hollows, plants itself in close communion of fellowship, or suspiciously scatters itself over a wide expanse of sand,” a Perth writer noted in 1914.

Observers of the Australian suburb echoed contemporary English critics, like Wells and Masterman. By the time the Englishman got to Australia, he peered down from an even mightier height. “Each little bungalow was set in its own hand-breadth of ground, surrounded by a little wooden palisade fence,” Richard Somers, hero of D.H. Lawrence’s novel Kangaroo (1923) observed. “And there went the long street, like a child’s drawing, the little square bungalows dot-dot-dot, close together and apart, like modern democracy, each one fenced round with a square rail fence.” Long before Pete Seeger’s famous song “Little Boxes,” the intellectuals, of both the left and the right, had written the suburb in a diminutive, minor key.

In 1928, the Australian historian Keith Hancock returned from Oxford to confront, as though for the first time, the Australian suburb. “Behind the garden fences, and within the little bungalows of a working class suburb, there are cleanliness, fresh air, some of the comforts and all of the decencies of life,” he admitted. “But for the Socialist” (he was writing for the British socialist journal the New Statesman) “it will not be enough.” The Australian suburb, he decided, offered “comfort without taste.” It had democratised “the standards of a plutocracy.” Even its residents, he believed, were vaguely conscious of the “dullness and monotony of Antipodean suburbia.”

Hancock thought he knew the remedy. The trouble with Australian cities, he decided, was “the abuse of space,” a bad habit they had inherited from their English counterparts. “It is time to declare a revolt against England… We shall find better teachers in Stockholm, or Hamburg or Vienna.” Australia’s cities would become more civilised as they became better planned, more compact – in short, more European.

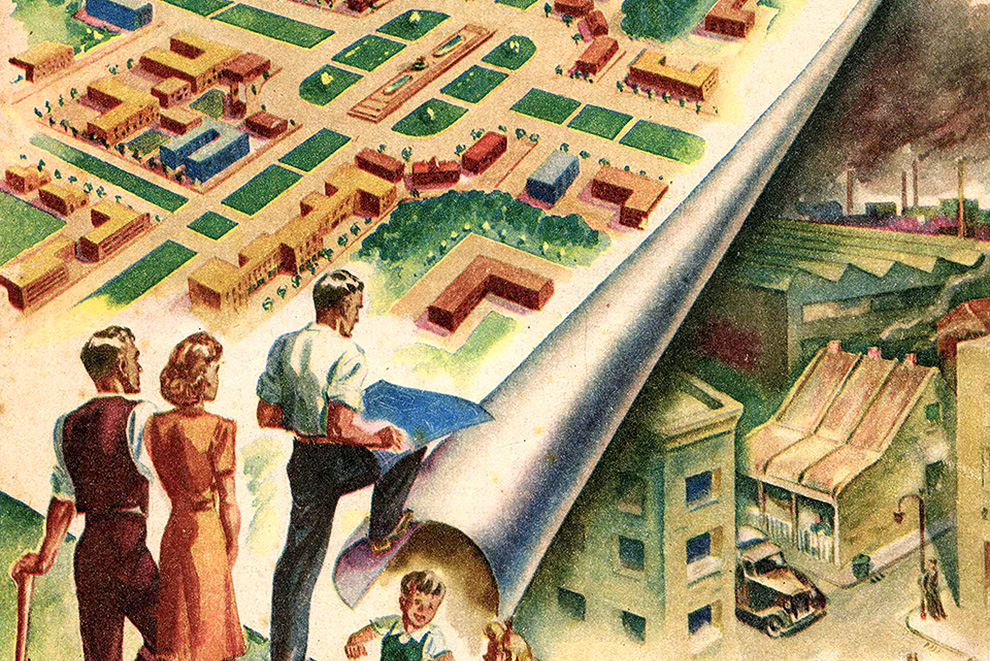

Fears of suburban sprawl fluctuated in response to cycles of enthusiasm for urban planning. The 1940s was one of the great dreamtimes in Australian history, when wartime austerity launched visions of a new social order, made tangible in ideal cities and suburbs. In 1948, Sir Patrick Abercrombie toured Australia, preaching the lessons of his 1944 London Plan. “Decentralisation,” “satellite cities,” “green belts” and “model suburbs” quickly became part of Australian public discourse.

Among postwar planners, “sprawl” was redefined as an economic disease, though without losing its moral connotations. The unplanned suburb was not just a blot on the countryside but also a symptom of economic waste and inefficiency. “With its ever-increasing sprawl Melbourne has grown too big for its economy,” the Melbourne Argus warned in 1952. “To save our city and ourselves from bankruptcy we must call a halt to the sprawl before it can run us into bigger bills.” The attack on sprawl was coupled with reports of failing urban services, tallies of unmade roads, sewers and tramways, and appeals for an urban growth boundary. Sprawl was to the body politic what obesity was to the human body. “Melbourne,” wrote architect Robin Boyd, “has become too fat, languid, its strength outgrown.”

New shapeless suburbs sprawl heavily on the surrounding country. They grow without grace, without charm, far beyond the reach of the metropolitan transport system, beyond the last call of the milkman, beyond the gas, the sewerage, the shops, the theatres, the hotels. The city is putting on weight without muscle.

The antidote to sprawl, according to Abercrombie and Boyd, was not densification, but good planning and better suburban services. The metropolitan planning schemes adopted by Sydney and Melbourne in the 1940s and 1950s followed their lead, proposing green belts, activity centres and firmer metropolitan boundaries, but seldom directly challenging the low-density suburban way of life. “There are no definite boundaries where an observer can say: ‘Here the city ends and the country begins,’” Victoria’s Town and Country Planning Board noted in 1950.

By the 1950s, “suburbia” was becoming a metonymy for a new range of complaints. As well as architectural dullness and “oppressive conventions,” it was supposed to produce “effeminacy,” “loneliness” and political apathy, according to various critics of the time. “Nine out of ten of the little women in suburbia are content to leave political decisions to the mastermind of the house,” a political writer lamented in 1952. Women were also the chief victims of a mysterious disease imported from the United States, called “suburban neurosis.”

Defenders of suburbia had to defy an undertow of intellectual condescension. Australia’s most popular women’s magazine, the Australian Women’s Weekly, deplored the “scorn” of students and other “sham sophisticates” towards suburbia. “Of course it’s largely suburbia, but why should one be afraid of that name?” asked historian Charles Bean, in defence of his home, Canberra. “Twenty-three years as Australia’s war historian taught me how much that is magnificent can come from our decent suburbs with their little homes and gardens.” Even suburbia’s defenders, it seemed, could not escape the diminutives, “little” and “decent,” that seemed to haunt its name.

By the 1960s, Australian critics of suburbia were often taking their cue from the United States rather than Britain. As a disciple of Patrick Geddes and admirer of the English Garden City, American historian Lewis Mumford aspired to a new, more organic relationship between city and country, technology and nature. In his 1938 book, The Culture of Cities, he recognised the romantic suburb as expressing a “rational purpose” – the attempt to create “a biological environment on an urban basis.” If it was to be criticised, it was not for what it did, but for what it failed to do. By the time he came to write his most influential book, The City in History (1961), however, Mumford’s opposition had hardened. The democratisation of the suburban idea had fatally compromised its original promise. Residents of the postwar suburbs enjoyed neither society nor solitude. The dormitory suburbs were not just “child-centred,” but also expressed “a childish view of the world.”

The suburb, Mumford declared in one of his more colourful passages, was “an asylum for the preservation of illusion.” In his mind, it was always to be contrasted with the city, the real world, where the great issues of civilisation are being played out, and where the rich share civic responsibility with the poor. The worst effect of the logic of avoidance, in Mumford’s scale of values, was the avoidance of responsibility.

Since the emergence of the first modern suburbs in the 1830s, the ideological foundations of the suburban idea have gradually crumbled. The sentimental idea of Home as a haven in a heartless world survived the decline of evangelical Christianity, and even its secularised version, Respectability. By the 1970s, however, the family was itself undergoing radical changes, especially the massive entry of married women into the paid workforce. The sanitarian’s belief in the healthiness of a semi-rural environment proved more tenacious than the anti-contagionist theories of disease on which it was based, yet by the 1970s the automobile suburb was generating new pathologies of its own and environmentalists were beginning to condemn the suburbanites’ profligate use of land and water as vigorously as their forefathers had condemned the squalor of the slum. Modernist architects and planners had rebelled against the nostalgic and romantic impulses that had inspired so much of the physical character of the suburbs. And, most significantly of all, the application of the techniques of mass production, and the postwar building boom so universalised the suburban form that its character as an exclusive middle-class retreat was finished forever.

It was not really until the 1960s that social scientists began to question the determinist logic that underlay what one of them now dubbed “the suburban myth.” Both the traditional critics and the defenders of the suburb had succumbed to the same flawed logic. Because the suburb was intended to foster domesticity, health, beauty and class solidarity, they assumed that it did so, and differed only on whether these were the highest values. It was only when the suburbs became more extensive and diverse that people began to recognise that you could find just as much domestic misery, ill-health, ugliness and class conflict in the suburbs as in the city. Conventional accounts mistakenly equated the suburbs, as a built form, with the ways of life of the middle class who monopolised them. But working-class suburbs, as the American sociologist Herbert Gans argued, could exhibit ways of life and outlook as diverse as the people who lived in them.

A rash of Australian studies added to the doubts. Robin Boyd’s The Australian Ugliness (1960) deplored the “uglification” of the countryside as tree-haters and featurist architects shaped the new suburbs. Patrick Tennison’s The Marriage Wilderness: A Study of Women in Suburbia (1972) depicted the loneliness and depression prevalent among suburban housewives. Political scientists probed the complex interrelations between location, class and politics on Melbourne’s suburban fringe and the “circumambient apathy” that seemed to envelop it. Hugh Stretton’s Ideas for Australian Cities (1970) offered the most penetrating discussion of the trade-offs between urban density and the suburban way of life. Yes, he agreed, “plenty of dreary lives are indeed lived in suburbs. But most of them might well be worse in other surroundings.”

Paradoxically, it was the realisation of the suburban dream that finally proved its undoing. Only when almost everyone was a suburbanite did it become clear that similar places could mean different things to those who lived in them. Social critics were quicker to spot the determinist flaws in the idea of the slum than they were to recognise the similar skewed logic in the idea of the suburb. Rather than surrender their disapproval, they sometimes preferred to detach “suburbia” – a metonymy for a loathed way of life – from the geographical entity, the suburb.

Anti-suburbanites have been as slavish in their imitation of international fashions as the suburbanites were before them. The uncritical adoption by Australian commentators of the pejorative term “McMansion” illustrates this tendency. In fact, the material and social character of suburbanisation in the two societies are very different. In the United States, the middle classes have deserted the inner city for the suburbs, largely in order to avoid the costs and risks of sharing the inner city with poorer black and Hispanic neighbours. Some of the most criticised aspects of American suburbia, such as gated communities, fiscal selfishness, religious and political conservatism – and now sub-prime loans – are shaped by forces that are either absent, or much less powerful, in Australia. Here, by contrast, the upper middle classes have been deserting the suburbs in droves, forsaking the haciendas and swimming pools of Commodore Country for the terrace houses and restaurants of Cappuccino Country.

The most serious strike against the suburb is now environmental: its profligate consumption of land, energy and water. “We are full of regret for our gluttonous consumption of space and now we are questioning the ideology on which our lifestyle is based,” journalist Tony Collins observed in 1993. “As a nation we are in therapy, slowly coming to terms with the consequences of our over-indulgence.” Collins was preaching a new austerity on behalf of the Hawke government’s Better Cities Program and its policy of urban consolidation. Over the century since it was first coined, the concept of “sprawl” had metamorphosed from an aesthetic, to an economic, and finally to an ecological concept, while never losing its strong negative charge.

The suburban idea was losing its moral legitimacy. The new anti-suburbanism in Australia echoed the arguments of North American critics, inveighing against gated communities (even though there were few in Australia), nostalgic cookie-cutter architecture, and the false comforts of home ownership. After two decades of moralising, the critics have succeeded, not in killing the suburban ideal, but in cutting it down to size. Among the intellectuals they have not had it all their own way, although doubts about the value of urban consolidation do not necessarily translate into a full-blooded defence of the suburban idea.

After two centuries on the rise, the tide has turned against the suburban idea. The physical form has survived the ideologies that gave it birth. The suburbs continue to grow, although more slowly than before. The forces that sustain them are economic and pragmatic and they now have to swim against the tide of public opinion rather than with it.

The most desirable ways of living in Sydney and Melbourne are increasingly dense, urban and cosmopolitan rather than sparse, monocultural and suburban. The suburban fringe has become the refuge of the new poor rather than the new rich. It residents must endure not only the disadvantages of inferior public transport and services, but also the disdain of the inner-city intelligentsia. Real estate promoters still invoke the familiar rhetoric of rus in urbe, or attempt to graft it onto the language of urban sophistication. (“Latte by the Lake” was the slogan of one recent suburban development on Melbourne’s western edge.)

But the suburban idea is more like a marketing stratagem than the powerful ideology it once was. Its day is not yet over, but its heyday has passed. •

This is an edited extract from City Dreamers: The Urban Imagination in Australia, published this month by NewSouth.